One of the largest and most comprehensive collections of Native American art in private hands is on longterm view at New York’s Metropolitan Museum. We couldn’t ask for more in an exhibition, for the purely aesthetic pleasure these objects give, for gaining a fuller understanding of their cultural importance, and for seeing indigenous art in the context of American art history.

When the Metropolitan Museum referred to the items in their Art of Native America exhibition as “masterworks”, they weren’t just being hyperbolic. We’ve seen a broad variety of indigenous aesthetic forms and media — but none that surpass the Charles and Valerie Diker Collection.

The Dikers have for almost half a century been ardent collectors of Native American art, with the intention of preserving exceptional examples of the craftsmanship and aesthetics of indigenous cultures. Two years ago the couple gifted 91 works from their collection to the Metropolitan, to join 20 works they had previously donated. Of the Met’s stewardship going forward, Mr. Diker says, “We are confident that both public recognition of the power and beauty of these works and scholarship on them will be greatly advanced.”

“These superb works will be an extraordinary addition to the Met collection,” says Carrie Rebora Barratt, Deputy Director for Collections. They “are of the highest aesthetic quality [and] will considerably strengthen our holdings of the artistic production of native communities.”

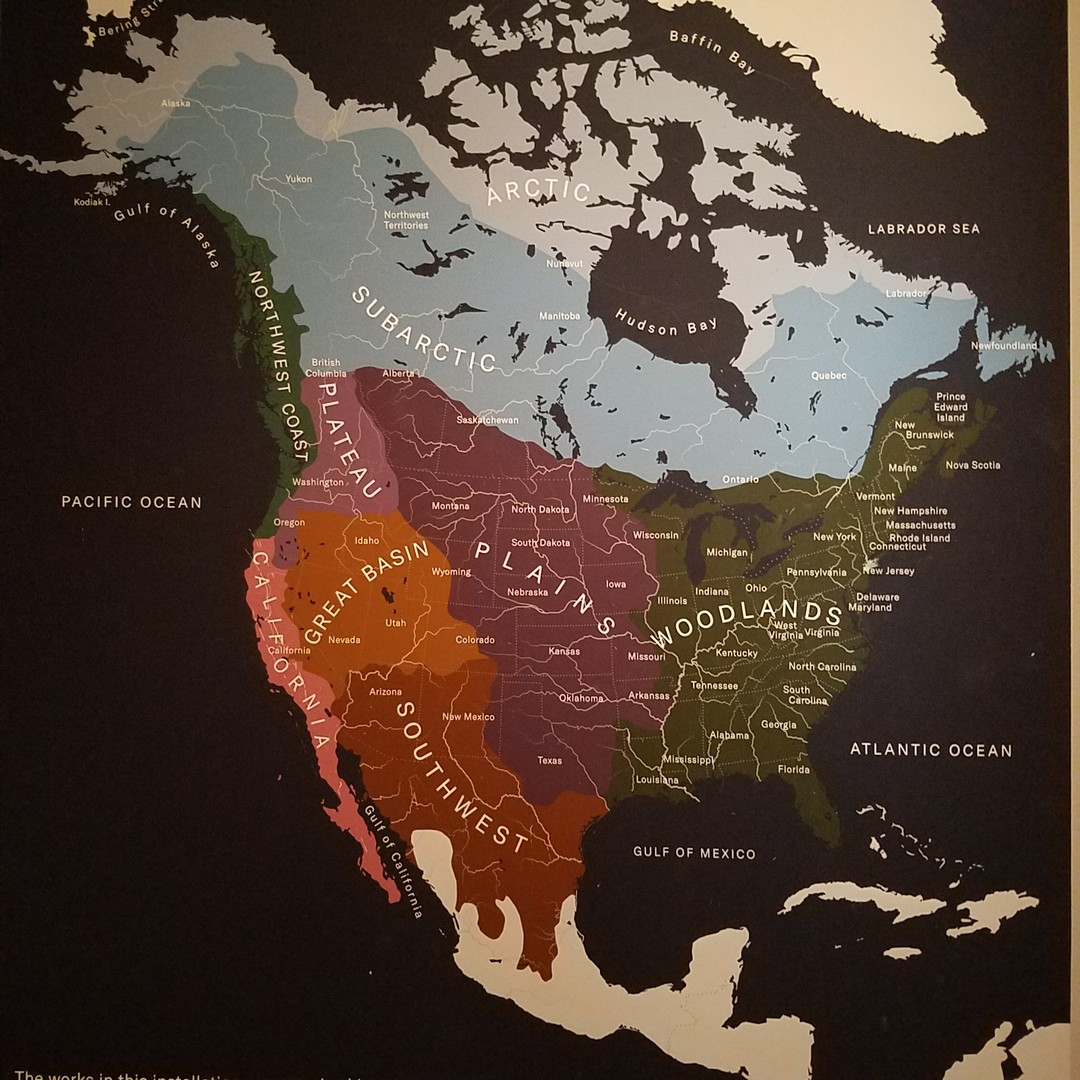

The exhibition is organized by geographic regions across the United States and Canada. A large map identifies the original lands of each peoples, in seven geographic groupings: Woodlands, Plains, Plateau, California and Great Basin, Southwest, Northwest Coast, and Arctic.

Of course these cultural-area designations are less relevant today as they once were. While many native peoples continue to reside within their ancestral homelands, others live elsewhere in North America and beyond.

This graphic reminder of the sheer scope of indigenous dispersion sets the stage for the variety of artifacts in the installation, and for noting the differences of style, material and technique used in their production.

The 116 masterworks in the exhibition reflect the artistic achievements of culturally-distinct indigenous peoples. More than 50 indigenous groups are represented, as are most major traditional Native American aesthetic forms: painting, drawing, sculpture, textiles, quill and bead embroidery, basketry and ceramics.

Most of the objects – made to clothe; to store, prepare and consume food; to hunt, defend and protect; to heal; to cradle infants; and to invoke the spirits – were created in the 18th, 19th, and early-20th centuries against the backdrop of European exploration and settlement.

We were awed by the consistently exemplary quality of the objects in the Diker collection. Time and again as we moved through the exhibition we were transfixed by the artistic sensibility and craftsmanship. From intricate beadwork and skilled weaving to expressive wood carving and ledger drawings — from the purely practical to the purely spiritual — the fascinating narrative told by these masterworks is the history of indigenous North American cultures.

Ranging in date from the 2nd century, through the period prior to contact with European settlers, to the early-20th century, the works include sculpture from British Columbia and Alaska, California baskets, pottery from southwestern pueblos, Plains drawings and regalia, and rare accessories from the eastern Woodlands.

Although the hundreds of distinct North American Native cultures each had their own language, religion and traditions, they did have one thing in common: a division between men and women regarding which arts each gender practiced. Textiles, pottery, basketry, and beadwork, for example, were women’s work. Men made carved artifacts associated with spiritual ceremony, hunting and war, they worked with silver and feathers, and produced representational and visionary painting.

It’s worth noting that, today, many contemporary Native American atists still adhere to these traditional roles, while others have set them aside to explore other avenues of artistic expression. The considerable skill and ceativity of indigenous artists today can be appreciated (and purchased) at the highly-competitive annual Santa Fe Indian Market held in Santa Fe, NM each August. It’s the world’s largest and most highly acclaimed Native American arts show, drawing artists from across the US and Canada. (Santa Fe is also home to the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts. Read our article about our visit here.)

A few of the artifacts in the Met show that particularly wowed us are highlighted below — but there is so much more to the exhibition! You can see the full roster of objects in the exhibition at the The Metropolitan Museum website here.

Innu/ Naskapi, Eastern Quebec and Labrador, Canada

Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection of Native American Art

The people of the vast Labrador Peninsula have a long-held belief that well-made hunters’ clothing honors the spirits of the animals and unites hunter and prey. This tailored hunter’s coat – on which a tribal woman painted intricate, geometric designs to please the caribou – embodies that belief. The garment blends European fashion into Indigenous tradition. The fitted waist is typical of Innu (Naskapi) clothing, while the flared skirt reflects French colonial styling.

In the mid-19th century, Cree and Ojibwa women wore wool hoods for travel, church, and ceremonies. The designs were typically made up of three panels of floral motifs and fringes of beads. The stylized, lacelike composition graces the earlier of two James Bay Cree examples in the exhibit, shown above. Recent historical research suggests the hoods may have been encrypted with spiritual meanings.

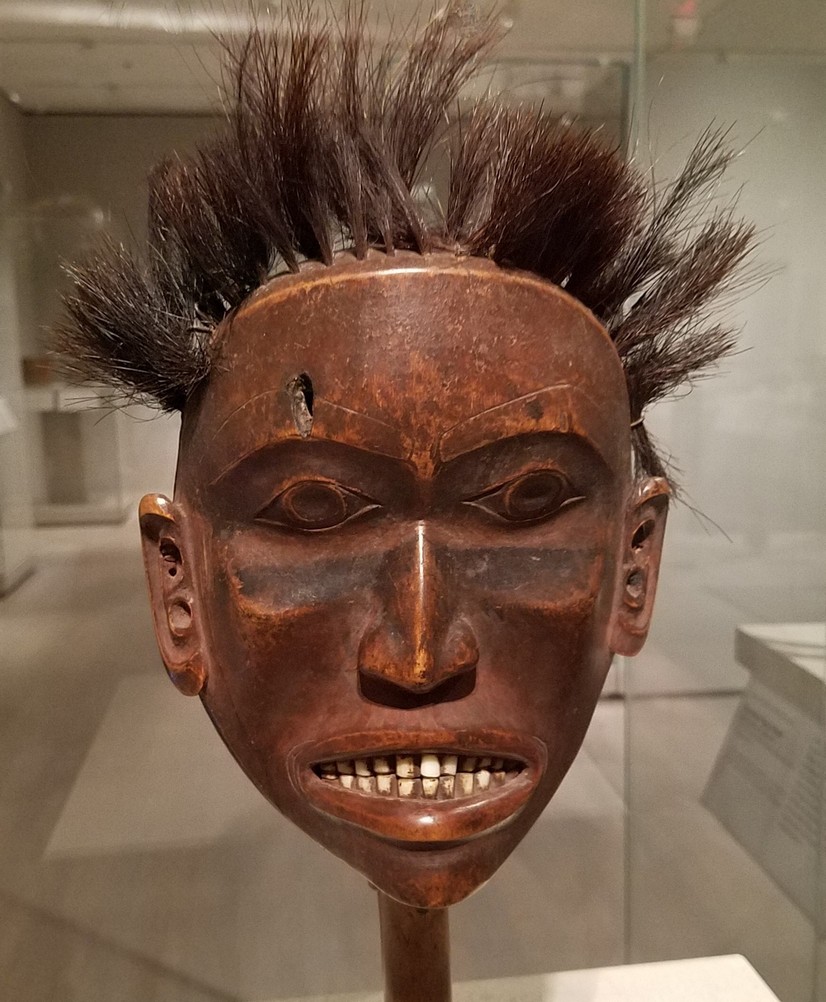

Tsimshian, Pacific Northwest Coast

It’s unknown whether the emaciated human face on the front of this shaman’s rattle represents a spirit being or the shaman himself. The skull is prominent beneath tightly drawn skin, the figure apparently hovering between life and death. On the back, intricate incised formline imagery portrays one or more spirit helpers. (Typical of Northwest Coast Indian art, formlines are curvilinear, flowing lines that turn, expand, and diminish in a specified way.)

A healer would have used the rattle to invoke supernatural assistance, and he may have commissioned an experienced artist to carve it. Tiny pebbles inside give the instrument its percussive sound.

Man’s mocassins ( ca. 1870), Comanche, Texas or Oklahoma

Native-tanned leather, glass beads, and pigment

In many Native cultures, women raised the making of moccasins to a high level of artistry. This Comanche pair features narrow lanes of geometric beadwork, beaded tongues, green-dyed fringes, and long rectangular tabs with fringes at the heel.

The beaded child’s moccasins are detailed with animals associated with spiritual power and protection: deer encircle each foot and a Thunderbird embellishes each sole. The fully-beaded soles, typically a Lakota style, speak to the wealth and prestige of the family and are an expression of affection for the wearer.

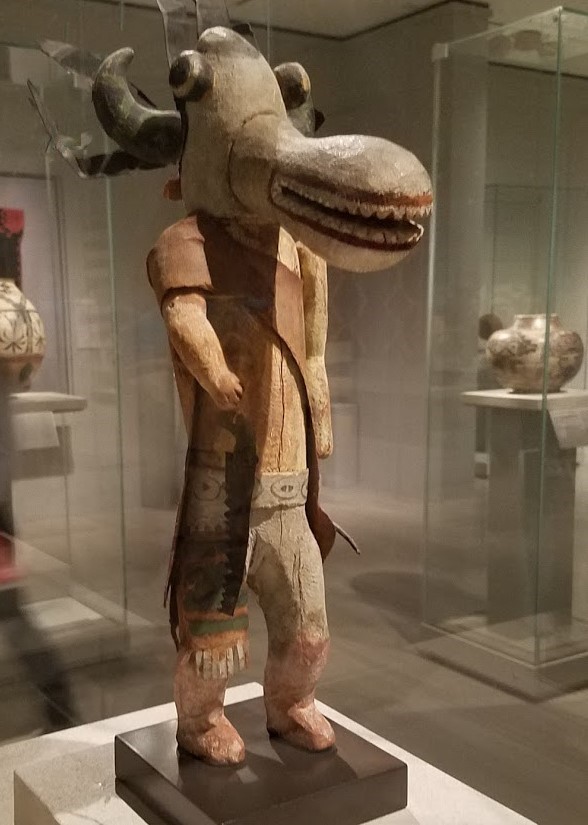

Hopi / Arizona; Cottonwood, pigment, cotton cloth, native-tanned leather, and metal.

A katsina figure is a spirit being who serves as a cultural guide in Hopi and Zuni communities. Young girls often receive a tihu, or katsina doll, as a cherished gift. The katsinam assume physical form during Pueblo ceremonies to dance and send prayers to the spirit world.

In the 1920s, Hopi and Zuni carvers began producing katsina dolls to sell to tourists, as demand for Native American souvenirs grew steadily at the turn of the century.

This tihu takes the form of the ogre Nata’aska, who visits Hopi villages to discourage bad behavior and to remind children of their responsibilities to their community.

Don’t be fooled by how cute this bug-eyed little guy is. The figure, dressed in traditional regalia — concha belt and hip sash — carries a bone-cutting saw!

Cedar bark, mountain sheep wool and dye

Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection of Native American Art

This tunic and leggings would have been worn for celebrations by a high-ranking leader of the Chilkat community of the Tlingit people. The raven images refer to the emblems of his clan, and the masklike faces represent his revered ancestors.

In a painstaking process, a woman artisan of the Chilkat finger-wove the pieces by suspending the warp threads from a bar weighted at the bottom with rocks. A male artist would have created a pattern board, or painted instruction sheet, to serve as her guide.

Right: Cradleboard (ca. 1890), Ute. Wood, native-tanned leather, pigment, glass beads, wool cloth, metal cones, feathers, and bone

A cradleboard allowed the baby to be carried on the mother’s back, suspended from her saddle, or propped against the tipi.

In most Plains cultures, traditionally a new mother’s relatives made a cradleboard for the baby. The intricate, colorful beading on the example shown on the left are part of traditional Kiowa designs created by women. This one shows considerable use; it appears to have cradled many babies over generations.

Ute relatives made the cradleboard on the right using yellow ocher for a baby girl; they would have used white clay paint for a boy. The wooden backboard is covered in leather and ornamented with geometric and curvilinear designs in pigment and beadwork. A hood of thin wooden rods provided protection if the cradleboard tipped forward and also shielded the baby’s eyes from the sun.

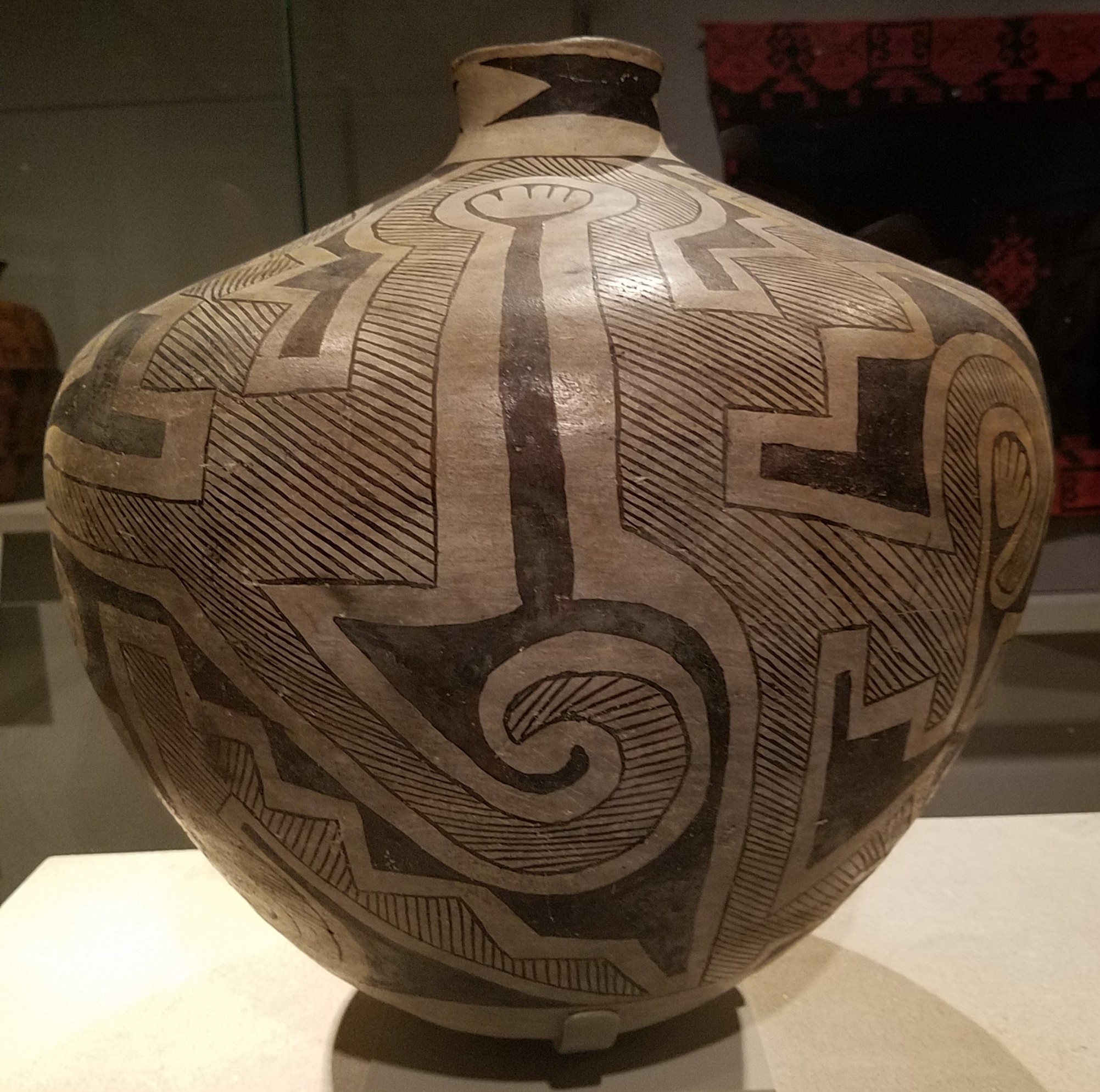

At almost 1000 years old, this beautiful Socorro pot is in extraordinary condition. It would have been used by ancestral Pueblo peoples to store dried food. It’s striking in how contemporary-looking the surface pattern is, with its abstract black and white forms seeming to float on the finely-hatched background.

Polacca Polychrome Water Jar, Arizona, ca 1895-1900

Clay and pigment

This rustic water jar was made by Nampeyo, who was a leading influence in late historical and early modern Pueblo pottery. Living on First Mesa, Arizona, high above the desert, her remote village was visited every year by the ceremonial katsinam, ancestral spirit messengers who sent prayers for rain, bountiful harvests, and a prosperous, healthy life. The significance of this annual event is captured on this jar, which is decorated with painted representations of four katsinam encircled by a rainbow.

Black-on-Black Jar, 1919–20, San Ildefonso Pueblo, Santa Fe, New Mexico; Clay and slip

Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection of Native American Art

Another Southwestern pot in the collection is a black-on-black jar by Maria Martinez. She and her husband, Julián, are among the most widely acclaimed ceramic artists of the 20th century.

By the late 19th-century, Spanish tinware and Anglo enamelware had become readily available in the Southwest, reducing the need for clay pots. As a result, traditional pottery-making techniques were being lost, but Maria and Julián were driven to preserve the art. They tried various techniques until their experiments led to the development of a process for making an unprecedented, iconic black-on-black pottery. Working as a team, Maria shaped the vessels and Julián painted the designs.

This jar — produced in the early stages of their experimentation — features a matte surface and a polished image of Avanyu, a Tewa deity and guardian of water. Later jars featured varied combinations of polished and matte backgrounds and imagery.

Their black-on-black pottery remains the standard for San Ildefonso Pueblo potters today.

Sedge root, willow shoots, glass beads, and abalone shell

One of the world’s great basketry traditions originated thousands of years ago by Native artists, primarly women, in the area that is now California and Nevada.

Like ancent pottery traditions, basket-making suffered as Anglo settlers brought change to the region. Livestock introduced into the region destroyed many of the plants used to make baskets, and manufactured products presented alternatives. Fortunately, Native artists revived the tradition in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and several basket makers achieved unprecedented levels of technical and aesthetic refinement.

While more than half the fourteen baskets in the collection date to the early 20th century, some examples were produced as long ago as 1780. The materials used varied by region, some plant fibers dyed and others left in their natural colorations. Some artists wove glass beads, abalone shells and even quail topknot feathers into their creations.

The two baskets shown were made as gifts, and signify wealth and prestige. The smaller one, behind, is entirely encrusted with beads, and the rim is decorated with clamshell disks and quail topnots. The basket in the foreground has bead and abalone shell pendants dangling from the rim and around the beaded body.

Charles and Valerie Diker have an unwavering belief in the potential of these objects to broaden understanding of Native American history, culture and aesthetics. Their donation was made to the museum under the condition that the collection “would be presented as American art rather than tribal art,” says Charles Diker, “perhaps to recontextualise what we define as American culture. … It is the first show of Native American works to be presented as ‘American art rather than tribal art,'” he says.

We’ve pictured 15 artifacts from an array of 116 objects, all of outstanding quality, historical interest and cultural importance. This is an exceptional collection of Native American art, and if you are in New York City, it’s a not-to-be missed exhibition.

Hmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a lttle trip!

Art of Native America: The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the search engine that makes it easy to discover more than 1300 art museums, historic houses and artist studios, and gardens across the US.

Featured Headline Image: Katsina figure, Hiilili Kokko, ca. 1900, New Mexico; Cottonwood, pigment, cotton cloth, wool yarn, native-tanned leather, feathers, horsehair, vegetal fiber, metal, and paper

Hi, I was wondering if you would like to showcase an art sculpture of the origianl Eagle Boy from Lowell Talamosha Sr. 8/35

I can attach photos of it for you to view.

Thank you,

Rosemarie Profeta

203-550-9131

Thanks for contacting us Rosemary, and thank you for this offer. However, I’m afraid showcasing individual pieces of art, outside of exhibition reviews, is not something we do in this blog. Best regards.

Thank you for this offer, Rosemarie, but we don’t feature individual artworks outside of exhibition or artist reviews. Best regards.