The names of two men — both sons of considerable wealth, born in the 1870s, and both culturally- and creatively-inclined — were widely recognized in the early years of the 20th century. Their celebrity was well-deserved at the time — and deserves to live on.

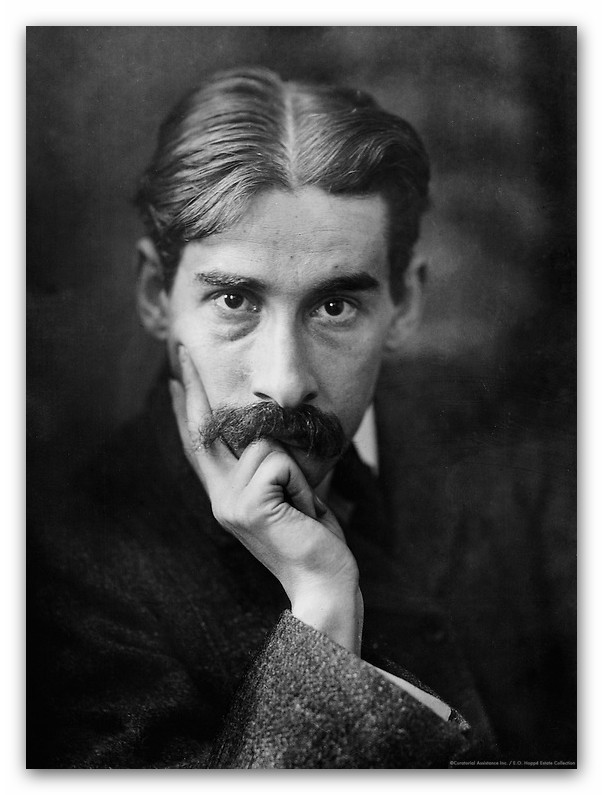

Sergei Diaghilev (1872 – 1929) was a Russian art critic, patron, ballet impresario and founder of the Ballets Russes, a dance company which revitalized ballet’s popularity around the world and produced many famous dancers and choreographers.

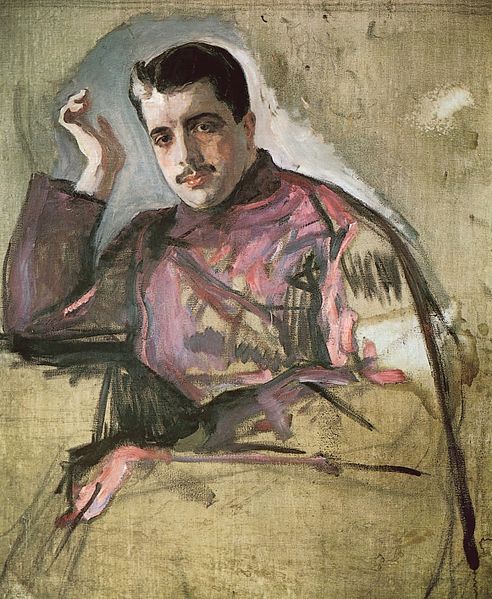

Léon Samoilovitch Bakst (1866-1924) , oil on canvas

The Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

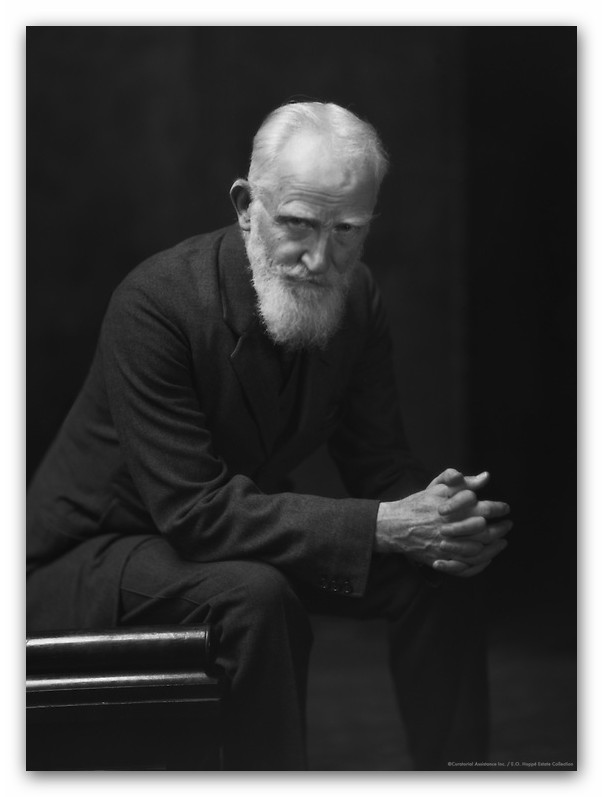

Emil Otto Hoppé (1878 –1972) was a German-born British portrait- and travel-photographer. Raised in Munich, he moved to London in 1900 to train as a financier. It wasn’t long, though, before he got hooked on photography and, in 1907, he turned his back on a career in commerce and opened a portrait studio. Within a few years, E.O. Hoppé was the undisputed leader of photographic portraiture in Europe.

Currently at the Museum of Russian Icons in Clinton, MA is an exhibition — Emil Hoppé: Photographs from the Ballets Russes — that pays homage to the genius of these two men, exploring the intersection of their creative endeavors. More than a century ago, Diaghilev founded the incomparable Ballets Russes and, between 1911 and 1921, Emil Otto Hoppé chronicled in black and white the champions of that illustrious company. Emil Hoppé: Photographs from the Ballets Russes is on through March 8, 2020.

It can be said that Serge Diaghilev singlehandedly triggered a Parisian rage for the arts of Russia and revived ballet in the early years of the 20th century. In 1906 he organized a major exhibition of Russian paintings for the Petit Palais in Paris, and over the next two years he followed that success with numerous concerts of Russian music and a production of Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov at the Paris Opéra.

Then in 1909 he returned to Paris with a ballet company that presented the best young Russian dancers, including Anna Pavlova and Vaslav Nijinsky. Most of the dancers were resident performers at the Imperial Ballet of Saint Petersburg, whom he hired to perform in Paris during the Imperial Ballet’s summer holidays. Opening night was an absolute sensation — and Diaghilev’s famous Ballets Russes was launched.

Coco Chanel is said to have stated that “Diaghilev invented Russia for foreigners.”

For two centuries traditional Russian ballet had been infused with conventions, designed to appeal to aristocratic Russian sensibilities. What made Diaghilev a great impresario was his ability to deliver to the tastes of general audiences. He and Léon Bakst, artistic director for the Ballets Russes, developed a more complex, exotic form of ballet that thrilled all of Paris.

The Ballets Russes went on to perform throughout Europe and on tours to North and South America. A new style of music emerged at the turn of the century, and Diaghilev adapted a corresponding modern ballet. In 1910, he commissioned his first score from Igor Stravinsky, The Firebird, and they collaborated numerous times thereafter.

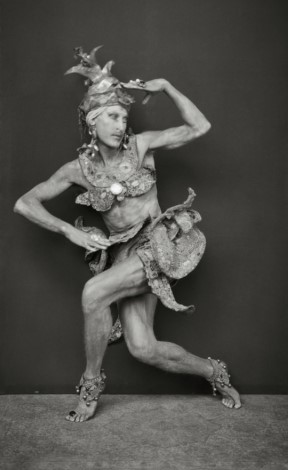

‘L’Oiseau de Feu’ (‘The Firebird’), London, 1911 / E.O. Hoppé Estate

He commissioned Maurice Ravel to compose the score for a ballet, Daphnis and Chloe, which was first performed in 1912. In the final part, Ravel used an unusual tempo — with five beats in a measure — and we’re told that dancers sang Ser-gei-dia-ghi-lev during rehearsals to keep the correct rhythm.

Diaghilev invited many contemporary Modernist artists to design sets and costumes, including such luminaries as Georges Braque, Matisse, André Derain, Miró, Giorgio de Chirico, and Dalí. He collaborated six times with Picasso for set production. These Modernist designs added another groundbreaking dimension to the excitement of the company’s productions.

The later years of the Ballets Russes were considered by some to be too “intellectual” or too “stylish” and few productions saw the wholesale success of the first few seasons. Nonetheless, young choreographers like George Balanchine made their name with the Ballet Russes, until 1929 when Diaghilev died and the company closed.

Diaghilev had never returned to his beloved homeland after the Russian Revolution of 1917. The new Soviet regime condemned him as an especially insidious example of bourgeois decadence and Soviet art historians wrote him out of their narrative for more than 60 years.

Today the Ballets Russes is widely regarded as the most influential ballet company of the 20th century. Diaghilev was a singular impresario, promoting ground-breaking artistic collaborations among young choreographers, composers, designers, and dancers, all at the forefront of their fields. The company was noted for the high standard of its dancers, most of whom had been classically trained at the great Imperial schools in Moscow and St. Petersburg. The company’s success may be attributed to the superb technical skill of the performers, as dance technique in Europe had declined markedly in the 19th century.

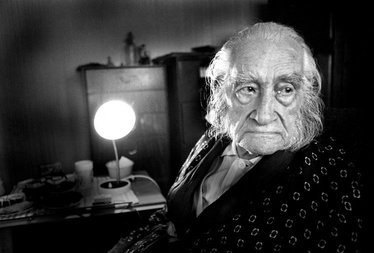

Although his name is not as widely known today as it once was, rarely has a photographer been as famous in his own lifetime among the general public as Emil Otto Hoppé was. Virtually every prominent name in the fields of politics, art, literature, and the theatre posed for his camera – and the photographer was as famous as his sitters.

In the 1920s and ’30s Hoppé was one of the most sought-after photographers in the world. His studio in London’s South Kensington was a magnet for the rich and famous, and for years he actively led the global photographic art scene on both sides of the Atlantic. He published more than thirty photographically-illustrated books, and established himself as a pioneering figure in photographic art.

How could his fame have declined so precipitously?

In 1954, at age 76, Hoppé made a fateful decision that rendered him to obscurity. He sold almost his entire body of photographic work to a commercial London picture archive where the photographs were filed by subject — in with millions of other stock pictures. No longer searchable by the photographer’s name, Hoppé’s archive was effectively lost to photo-historians and to photo-history itself.

Hoppé’s photographic legacy remained trapped for more than thirty years after his death.

Happily, in 1994, Hoppé’s life’s work again saw the light of day when the stock-photo collection was acquired by Graham Howe, a Los Angeles-based photographic-art curator and historian. Howe retrieved Hoppé’s images from the picture library and joined it with the Hoppé family archive of photographs and biographical documents. Finally, 40 years after that fateful decision – long enough for Hoppe’s fame to have waned — the complete E.O. Hoppé Collection was gathered together. Much effort has subsequently gone into cataloguing, conserving, and researching the recovered work, making exhibitions like this one possible.

With both studio portraits and ballet sequences, this visual narrative presents not only the leading stars of the Ballets Russes — such as Vaslav Nijinsky, Adolph Bolm, Michel and Vera Fokine and Tamara Karsavina — but also celebrities with who were tangentially connected with Diaghilev – such as Mathilde Kschessinska, Anna Pavlova, and Hubert Stowitts.

© E.O. Hoppé Estate Collection/Curatorial Assistance Inc.

The pure sensuality of Hoppé’s riveting Ballets Russes portraits reveals the essence of the dancers who, in performing their innovative choreography in costumes created by the contemporary bright lights of design and fine art, took audiences by storm with performances that shocked the senses and seduced the world into the modern era.

Comprised of 73 platinum prints and curated by USC Professor John Bowlt and Graham Howe, the exhibition was organized in collaboration with the E.O. Hoppé Estate Collection.

Emil Hoppé: Photographs from the Ballets Russes is on exhibit through March 8, 2020

Hmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a lttle trip!

Museum of Russian Icons

203 Union Street, Clinton, MA

978-598-5000

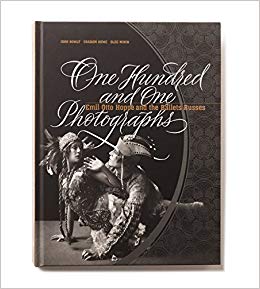

If you can’t make it to the exhibition — or even if you can — the companion publication, One Hundred and One Photographs: Emil Otto Hoppé and the Ballets Russes, pays homage to the genius of two men: Sergei Diaghilev who, more than a century ago, founded the Ballets Russes, and Emil Otto Hoppé, who, between 1911 and 1921, photographed the champions of that illustrious company. The pure sensuality of these portraits reveals the essence of the dancers who, in performing their innovative choreography in costumes by Léon Bakst, Nicholas Roerich, and Alexandre Benois, among others, took their audiences by storm with performances that shocked the senses and seduced the world into the modern era.

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the search engine that makes it easy to discover more than 1300 art museums, historic houses and artist studios, and gardens across the US.

Featured Headline Image: Tamara Karsavina as Columbine in “Le Carnaval”, London, England, 1912. © E.O. Hoppé Estate Collection/ Curatorial Assistance Inc.

I became a Ballet Russe admirer after seeing the Paris Opera Ballet (?) production of Petruska! It was magnificent! Such a beautiful ballet.