Claude Monet (1840 – 1926) — the “father of Impressionism” — lived to the well-weathered age of 86. Painting up until his death he continued to innovate, pushing into abstraction.

More than 50 paintings currently on view at the Kimbell Art Museum reveal a radical change in his late works.

oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Gift of Victoria Nebeker Coberly, in memory of her son John W. Mudd, and Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg 1992.9.1

Though the exhibition opens with a prologue of works painted at the very end of the 1890s, a selection of classic water-lily paintings from 1904–7, and two views of his garden painted around 1913, it highlights the evolution of Monet’s practice from 1914, when he returned to painting following a period of personal loss. His wife Alice died of leukemia in 1911, the following year he was diagnosed with cataracts in both eyes, and in 1914, as a World War was brewing, his eldest son died.

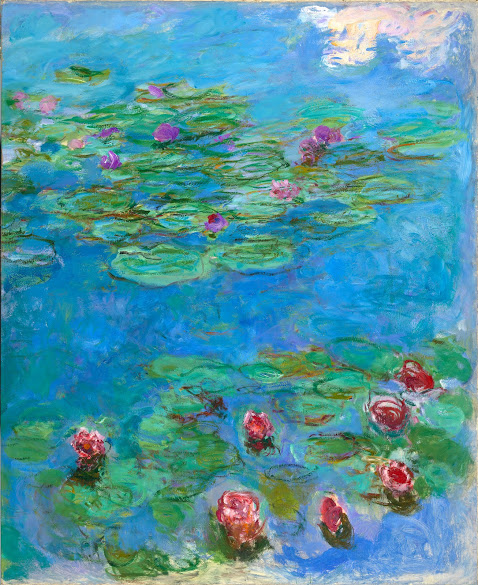

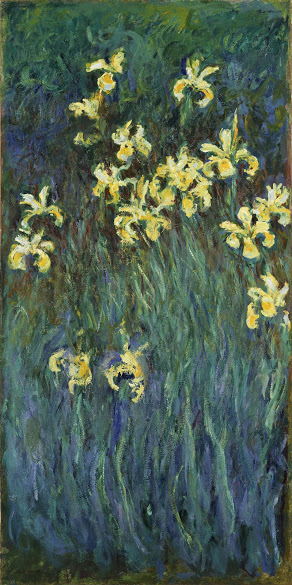

Oil on canvas, 55 1/8 x 47 1/4 in. (140 x 120 cm)

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris. Michel Monet Bequest, 1966

It was then, at age 74, that Monet began to reinvent his painting style and his work became increasingly bold and abstract. Expansive brush strokes, surprising color and minimal detail typify his later works.

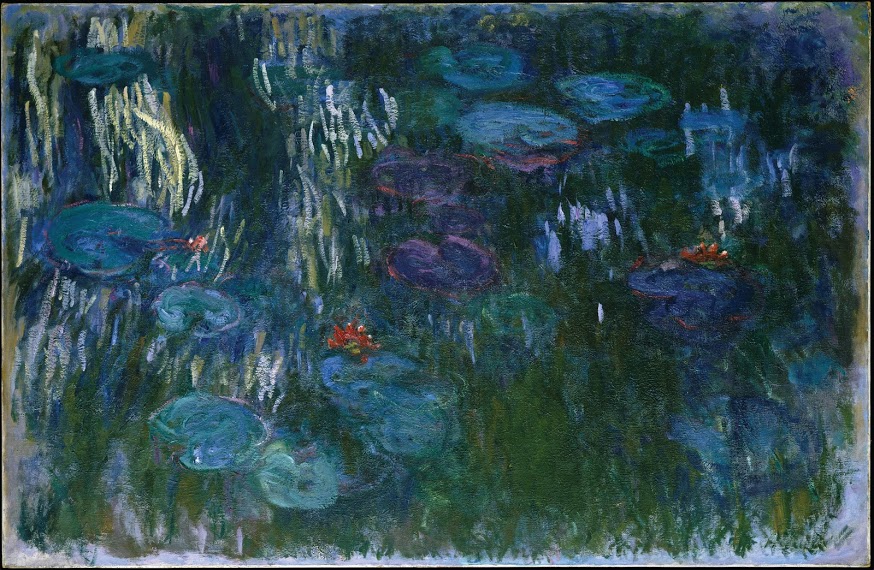

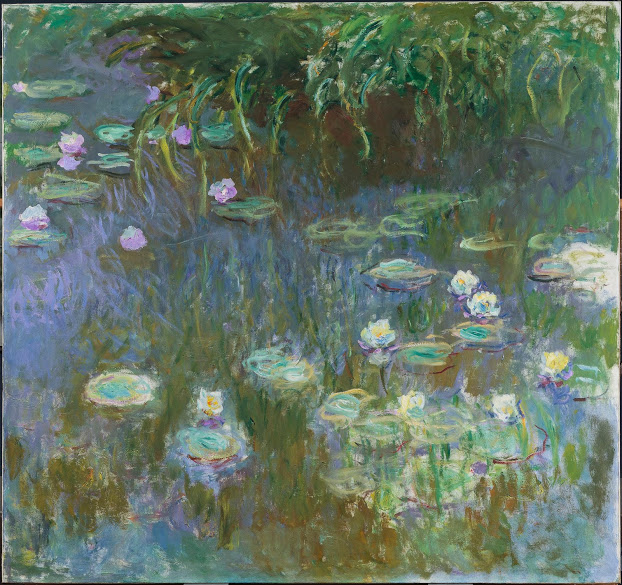

Oil on canvas, 51 1/4 x 79 in. (130.2 x 200.7 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gift of Louise Reinhardt Smith, 1983.532

The paintings in Monet: The Late Years have been assembled from major public and private collections in Europe, the United States, and Asia, including holdings from the Kimbell Art Museum and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

The show includes more than twenty examples of Monet’s much-loved water-lily paintings, plus many other exceptional and unfamiliar works from the artist’s final years, several of which are being shown for the first time in the United States.

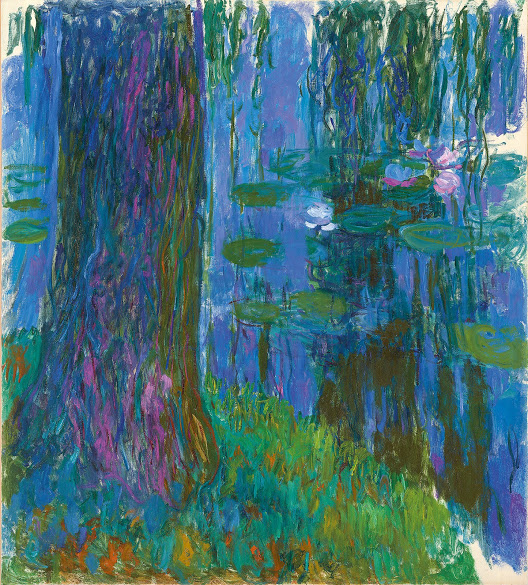

Oil on canvas 78 3/4 x 167 3/4 in. (200 x 426.1 cm)

Saint Louis Art Museum, The Steinberg Charitable Fund, 134:1956

Monet is only an eye, but my God, what an eye!

Paul Cezanne

Changes in Vision

Although Monet was diagnosed with nuclear cataracts in both eyes by a Parisian ophthalmologist in 1912, at the age of 72, his visual problems had begun much earlier. In his mid-60s he began to experience changes in his perception of color, no longer perceiving colors with the same intensity. Indeed, research at the University of Calgary’s Vision & Aging Lab points to a change in the whites and greens and blues in his paintings, with a shift towards “muddier” yellow and purple tones.

Oil on canvas 39 3/8 x 78 3/4 in. (100 x 200 cm)

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris. Michel Monet Bequest, 1966

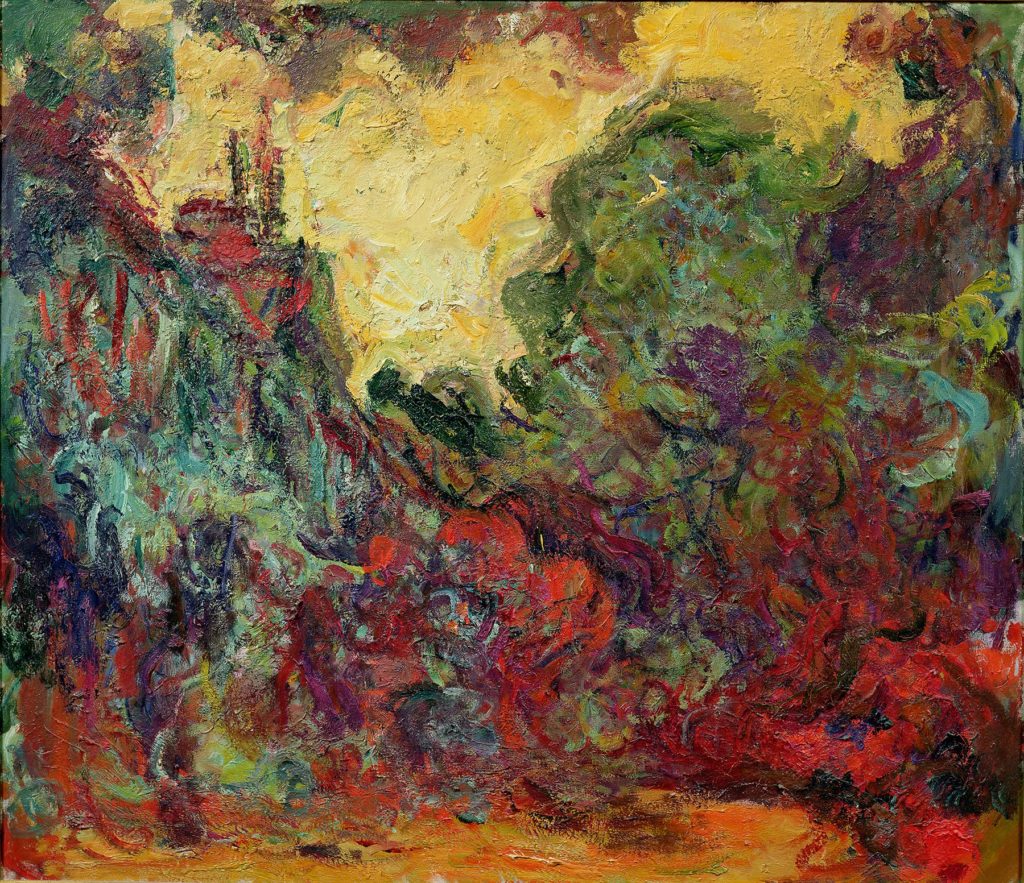

After 1915, Monet’s paintings became much more abstract, with an even more pronounced color shift from blue-green to red-yellow. Gone was the renowned sense of atmosphere and light. He complained of perceiving reds as muddy, dull pinks, and other objects as yellow. These changes are consistent with the visual effects of cataracts. Nuclear cataracts absorb light, desaturate colors, and make the world appear more yellow.

Oil on canvas 35 x 45 3/4 in. (89 x 116 cm)

Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Bequest of Putnam Dana McMillan

Monet was both troubled and intrigued by the effects of his declining vision. In a letter to his friend G. J. Bernheim-Jeune he wrote, “… my poor eyesight makes me see everything in a complete fog. It’s very beautiful all the same and it’s this which I’d love to have been able to convey. All in all, I am very unhappy.” – August 11, 1922, Giverny.

Monet knew about Mary Cassatt’s poor outcome with cataract surgery and he was reluctant to undergo the same procedure. He finally underwent a cataract operation on his right eye in 1923, when he was 82. The recovery period interfered with his work and initially he was dissatisfied with the results.

“… it makes me sorry that I ever decided to go ahead with that fatal operation. Excuse me for being so frank and allow me to say that I think it’s criminal to have placed me in such a predicament.” –

from letter to his Doctor, Charles Coutela,

June 22, 1923, Giverny.

While his right eye was again able to see violets and blues clearly, the left eye, clouded by a dense yellow cataract, could not. Nonetheless, Monet adamantly refused to have his other eye operated on. As a result of their difference in color perception and acuity, he was never again able to use both eyes together effectively. In order to distinguish colors, he maintained an established order of pigments on his palette.

He also had problems with glare that made working outside difficult. Fitted with glasses specialized for cataracts, he was able to read and continue his correspondence, but he complained that they caused him to see distorted shapes and exaggerated colors that were “quite terrifying”.

Oil on canvas 31 7/8 x 36 5/8 in. (81 x 93 cm)

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris. Michel Monet Bequest, 1966

Asked if the variations in color reflect what Monet was really seeing, or if he was making deliberate choices, the curator of the exhibition, George T. M. Shackelford — the Kimbell’s deputy director, and one of the world’s foremost experts on 19th-century French art — says, “We’re not able to pin this down with certainty. But we’re sure that we are seeing Monet doing his best to counteract the changes in his vision that we know are taking place.”

Monet’s Late Years

A range of paintings in the exhibition — from traditional pictures to canvases more than six feet high to a monumental work measuring 14 feet wide — demonstrate Monet’s continued vitality as a painter. Majestic panoramas are displayed alongside late easel paintings. The chronological display shows him to be one of the most original artists of the modern age, using bold methods of paint application, surprising harmonies or clashes of color, and striking scale.

The spring of 1914 was a turning point for the artist. He was “working at full speed, and no matter what the weather, I paint,” saying that he was undertaking “a huge labor, I am passionate about it.” He had begun a series of huge paintings, the most exhaustive he had ever attempted, on the theme of his water-lily pond, ideas he had first explored in the late 1890s.

Oil on canvas 65 3/8 x 56 in. (166.1 x 142.2 cm)

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Museum purchase, Mildred Anne Williams Collection, 1973.3

The work was exhausting. He wrote to his dealer Durand-Ruel, “you know that when I set myself to something, I set myself to it seriously, so much so that waking up at 4 o’clock in the morning, I labor all day and, come nightfall, I collapse with fatigue.”

The work was revolutionary. In a transformation that broke with the past, he had decided to accomplish, on a huge scale, the masterpiece of his old age, the Grandes Décorations, which installed after his death in the Orangerie of the Tuileries Gardens.

With the new project came a new way of working, a shift in the scale of every component of his art making. Among the works in Monet: The Late Years are some of the studies, each more than six feet tall and some 14 feet wide, that Monet painted beside the water-lily pond to record the effects that he saw there, so that he could bring them back to his studio for imaginative recombination and extension.

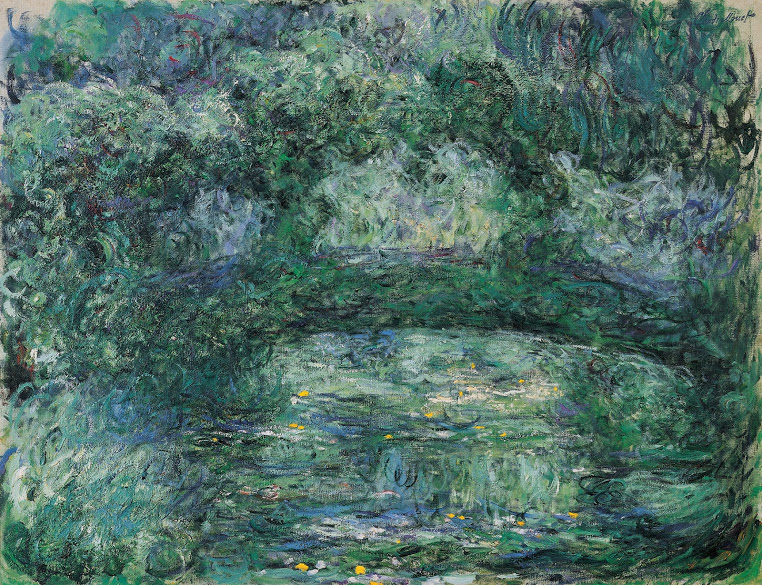

Oil on canvas 78 3/4 x 70 3/4 in. (200 x 180 cm)

Private collection

Among the works that he undertook after 1918 are several views of the garden above the water line, many of which have been gathered for this show. They include seven canvases depicting the Japanese bridge he had built over the narrowest spot in the pond.

Oil on canvas 35 x 45 1/4 in. (89 x 115.5 cm)

Fondation Beyeler, Basel, Switzerland, Beyeler Collection

Monet died in 1926, long after Cubism, Fauvism and other modern movements had emerged, and he would have been aware of these developments. The Kimbell’s Late Years exhibition heralds his lifelong vitality as a painter and shows that in his later years — with the suppression of detail in favor of increasing expressiveness – he was a pioneer of abstraction.

Monet saw his last works, however radical they might have become, as a continuation—we might now say a culmination—of a lifetime of studying nature. In his words: “My sensitivity, far from diminishing, has been sharpened by age, which holds no fears for me so long as unbroken communication with the outside world continues to fuel my curiosity, so long as my hand remains a ready and faithful interpreter of my perception.”

Oil on canvas 78 3/4 x 39 3/4 in. (200 x 101 cm)

The National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo

Other than the installation view of Grandes Décorations, at the Musée de l’Orangerie, all images shown are included in the Kimbell exhibition.

Featured headline image: Claude Monet, Water Lilies, c. 1921–22, oil on canvas, 79 x 84 in. (200.7 x 213.3 cm), from the collection of the Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio. Purchased with funds from the Libbey Endowment, Gift of Edward Drummond Libbey.

Monet: The Late Years

Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX

On through Sep 15 2019

Love his work. Went to L’orangerie in Paris to study his paintings. Beautiful! And the New Orleans Museum of Art had a show on Monets late works shortly afterwards! Fascinating to see how his vision had changed. I will have to go see the Kimballs exhibit too! Thank you!

Thanks for your comment, Laura. I, too, was fascinated to learn about the effect of deteriorating vision on his work. I have to admit, I wasn’t familiar with his late works beyond the water lilies and the cycle at l’Orangerie.