A hallowed place –despite the buffeting of time– the oldest church in the US is 400-year-old treasure, located in the Barrio de Analco National Historic District.

In the past it’s always been in Europe that we’ve indulged our love of old churches and their art and history. But since we’ve lived in the American SouthWest, we’ve become afficionados of old churches on this side of the Atlantic as well.

Ours may not be as extravagant as the great cathedrals of the Middle Ages or the Baroque churches of the Catholic Reformation, but the stories they tell of generations past are equally fraught with sacrifice and suffering, resplendent with hope and faith.

Catholicism was at the heart of Spanish Colonial daily life and the parish church was the center of the community, and — in what are now border states with Mexico — many of those churches still stand. While they welcome visitors, most still function as places of worship to the Catholic faithful.

This is the story of the oldest church in America.

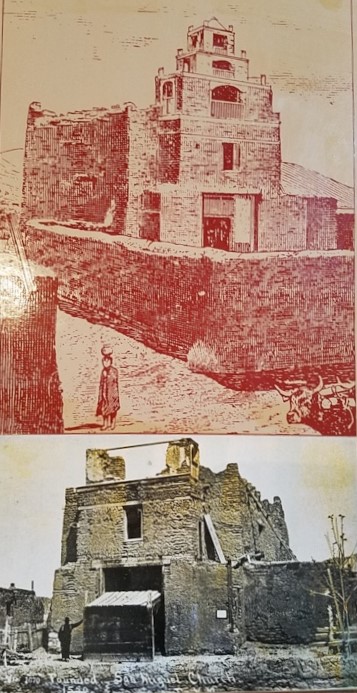

San Miguel Chapel, Santa Fe, NM

The earliest known documentation of the existence of San Miguel Chapel is from 1628. Oral history holds that the “Hermita de San Miguel” was originally constructed under the direction of Franciscan friars, ca.1610. The adobe church was erected on the site of an ancient kiva, and was built by Tlaxcalan (Tas-cal’-en) Indians who came to New Mexico from old Mexico in 1598 with a Spanish contingent led by Don Juan Oñate.

The little church served a small congregation of soldiers, laborers, and Indians who lived in the Barrio de Analco — so-named because the Tlascalan Indian word, “analco,” means “the other side of the river.” It distinguished this south side barrio from the plaza side of the Santa Fe River, where government officials and other prominent citizens resided and attended mass.

The chapel has been restored several times over the past 400 years.

San Miguel was partially destroyed in 1640 at the hands of a provincial governor who feuded with church authorities. It was reconstructed, but again severely damaged during the 1680 uprising of Pueblo Indians against the Spanish colonizers. After years of enduring the encomienda system of forced labor and forced conversion, the indigenous indians revolted against Spanish rule.

Analco was the first Santa Fe neighborhood the Puebloan Indians destroyed, and the Chapel of San Miguel was partially burned. 400 Spanish were killed and the remaining 2,000 settlers and most of their Tlascalan Indian servants fled to El Paso.

Twelve years later the Spanish returned and were able to reoccupy New Mexico with little opposition. They soon set about restoring the little church.

Time took its toll on the simple adobe structure, and a century later major repairs were needed. In 1798 the mayor of Santa Fe helped fund renovation, and it was then that the glorious carved and painted altar screen was added.

San Miguel Chapel, Santa Fe NM

Circa 1856, an elaborate three-tiered bell tower was constructed and a 780-pound bell — known as the San José Bell — was installed. Sadly, just 16 years later, a particularly violent storm blew through Santa Fe bringing down the bell tower and, along with it, the San José Bell.

The entire structure was seriously damaged and destabilized, but when the townspeople learned about the decision to demolish it, a hue and cry — and funds — were raised.

The stone buttresses that flank the entrance and lean into the north side were added to shore up the old building. The interior and exterior walls were plastered, a up-to-date tar and gravel roof replaced the vulnerable old mud roof, and a smaller bell tower was constructed. This work left the chapel looking much as it does today.

Access to the chapel today is through a side door via the gift shop where a paltry $2 fee is collected. Disappointingly, by not entering through the main doorway under the bell tower, we missed the awe-inspiring experience of immediately seeing, directly ahead, the hallowed wooden altar screen, or reredos.

San Miguel Chapel, Santa Fe, NM

Instead, we began by investigating the first thing that presented itself: the imposing San José Bell and the hundreds of tiny ex votos, called milagros, affixed to the sturdy supporting frame.

San Miguel Chapel, Santa Fe NM

Milagros (miracles) are metal charms that are offered to a particular saint to solicit help with a personal worry or to express gratitude for an answered prayer. Each milagro symbolizes the object of a petition: various body parts, for example, denote health concerns.

There’s a delightful legend about the Christian faithful contributing their gold and silver to the melting pot when the San José Bell was being cast in Spain in 1356. It is said that these two precious metals — which together make up 0.037% of the alloy — account for this bell’s mellow sound. A mallet is provided, inviting visitors to strike the bell to hear its surprisingly gentle, resonant tone.

Read our article for more about the marvelous tale of the casting and provenance of this ancient bell, how it came to be in Santa Fe, and the reason for the Spanish inscription that it bears — which translates to “St. Joseph, pray for us, August 9 of 1356”.

As engrossing as the bell and milagros are, the imposing altar screen — one of the oldest reredos in New Mexico, dating to 1798 — is the centerpiece, and not long ignored. (A reredos is what a screen behind an altar is called, from old French, arere behind + dos back.)

The reredos at San Miguel is thought to have been designed by the Laguna Santero, an artist who is anonymous today, but was influential in his time, and is known to have been working in the area between 1796 and 1808. (A santero is a creator of religious images.) The flanking solomonic columns are the first examples of this type of twisting column in New Mexico, and were something of a signature of the Laguna Santero.

It may seem hard to believe, but this entire altarpiece was painted over with two coats of housepaint in the late 1800s. We wondered why. Might it have had something to do with the politics that were swirling around the question of statehood for New Mexico at that time?

The population of the Territory of New Mexico was predominantly Hispano and largely illiterate, and their language and culture were completely alien to the Americans deciding who to allow to join the United States. For six decades, the three toos attitude prevented the Territory from joining the Union until 1912. It was too poor, too Mexican, too Catholic.

The New York Times refered to the territory as “the heart of our worst civilization … with all the signs of ignorance and sloth.”

While the railroad was bringing an influx of Anglos from the East into northern New Mexico, Santa Fe — the old “mud city” — was denigrated for its adobe houses and backward ways. There was a faction, though, who were in favor of statehood, and they strove to make New Mexico more acceptable. Thus, we speculated that their effort to minimize evidence of Catholicism may have provoked the whitewashing of the altarpiece.

But politics may have had nothing to do with it. A simple explanation for the whitewashing might be that the altar screen was shrouded with dirt and soot, and paint was the quickest, least-cost way to freshen things up.

Be that as it may, in a major 1955 restoration of the chapel the altarpiece was brought back to its intended state, cleaned and renewed.

The lowest tier holds a statue of San Miguel (St. Michael), carved in Colonial Mexico ca. 1700 and brought to Santa Fe by Franciscan friars. Above this is an 18th-century painting, Christ The Nazarene. In the center of the top tier is St. Michael the Archangel, painted in 1745 by Bernardo Miera y Pacheco, who is considered to have been the first New Mexican santero and an important influence on early santeros of the 19th century.

by Bernardo Miera y Pacheco

The four oval paintings flanking the two central paintings originated in Colonial Mexico in the early 18th century. Top right is St. Gertrude of Germany, with St. Louis IV, King of France below. Apparently the top left is St. Teresa of Avila (knowing Bernini’s Ecstacy of St Teresa in Rome, I never would have guessed!), and below her, St. Francis of Assisi.

Difficult to see, on the wall to the left of the sanctuary is a 15th-century Byzantine icon, Our Lady of Perpetual Sorrows. It’s a copy of an original icon from the Keras Monastery in Crete which has been in the Church of Saint Alphonsus in Rome since 1499.

Left: Greek original, now in the Church of Saint Alphonsus, Rome

Right: 15th century copy, in San Miguel Chapel

The walls of San Miguel are hung with more works of art, including a series of mid-20th century plaques representing the 14 Stations of the Cross. Two Annunciations flanking the altar are thought to be the work of a follower of Murillo, a leading 17th century Spanish artist who exerted considerable influence on Christian art in the Americas.

Two items of particular interest to us face each other on opposite walls: a Christ on the Cross painted on buffalo hide and a St. John the Baptist on deer skin. Believed to have been painted by Franciscan friars in the 1630s, the paintings were used as teaching aids to assist in converting the Pueblo Indians to Christianity.

Left: St. John the Baptist painted on deer skin

Right: Christ on the Cross painted on buffalo hide

The artistry carries overhead in the craftsmanship of the ceiling, with its beautiful, sturdy old beams. The hand-carved beam supporting the front of the choir loft is inscribed with the date, 1710.

As we prepared to leave, we almost missed the glorious action figure placed above the door. Wings unfurled, drapery a-flutter, this beautiful, muscular warrior is a copy of Guido Reni’s Archangel Michael Defeating Satan. The original, painted in 1636, hangs in the church of Santa Maria della Concezione in Rome). Don’t forget to look up as you exit!

San Miguel Chapel has been witness to history for more than four centuries. Located in the Barrio de Analco National Historic District, it’s a little treasure hidden in plain sight in “The City Different” that is Santa Fe, NM.

Hmmm … maybe its time to plan a little trip!

Please note: Since this article was published, the gift shop has closed, and the open hours may have changed. Please go to http://www.sanmiguelchapelsantafe.org for updates on visiting hours, entry, and preservation. The website is updated weekly.

San Miguel Chapel

401 Old Santa Fe Trail

Santa Fe, NM

505-983-3974

The Chapel is open to visitors when there is no Mass in progress.

The Schola Cantorum of Santa Fe sings Vespers and a Gregorian chant Mass every third Sunday of the month at 4:00 p.m.

The San Miguel Mission in Socorro, NM was built in 1626, damaged during the Pueblo Revolt in 1680, then rebuilt. It is older than the San Miguel church in Santa Fe, although not as well known. I tried to post a photo but was unable to do so–let me know if you would like to see it and how I can get an image to you.

Karyn, I did little research on San Miguel Mission in Socorro, and it appears that the original 1626 structure was so thoroughly destroyed that the replacement church, which opened in 1821, includes only a portion of one wall of the earlier building. From what I read it’s considered to be essentially a 19th century structure. Jane

San Miguel Church, Santa Fe, New Mexico. St. Michael the Archangel crushing Satan. This dates back to the mid-1700s, created by early cartographer and artist Bernardo Miera y Pacheco.

Hello,

Please see http://www.sanmiguelchapelsantafe.org for updates on visiting hours, entry, and preservation. This website is updated weekly. For example, there is no longer a gift shop.

Thank you,

L. Fiorentino

Director