A special exhibition at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art considers three centuries of the relationship between art, humanity, and nature.

Nature’s Nation: American Art and Environment (on through September 9, 2019) considers the complexity of the inter-connectedness of humans and the natural environment. Long inspired by nature, artists have often used their creative voices to call for the preservation of land, to bring awareness to environmental issues, and to encourage active stewardship of the earth.

This exhibition explores ways in which art has furthered understanding of changing environmental issues across this land, over the course of three centuries. How has the use of materials, techniques, subjects and contexts changed with time to support changing contemporary messages?

In the 19th century, American landscape paintings informed an eastern-states citizenry about the vast, varied, unspoiled lands across the continent, supporting the Manifest Destiny doctrine that claimed expansion of the US from sea to shining sea was desirable, justified and inevitable.

Lower Falls, Yellowstone Park (Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone), 1893

Thomas Moran was the official artist on the first US geological survey into Wyoming Territory in 1871, and his watercolor renderings of the dramatic scenery helped convince Congress to preserve the land and to create Yellowstone, the first US National Park.

It wasn’t long, though, before some artists began to feel the tension between optimism for America’s promise and concern about unregulated expansion.

While Thomas Cole’s early paintings glorified pristine wilderness, by the 1830s his landscapes were showing indications of human presence, like the ragged tree stumps leading from the foreground back toward the newly-built house in Crawford Notch (1839). “Thomas Cole was later understood to be an environmentalist, long before the term existed.”

Conscience-driven artists helped to raise awareness of the deliterious effects of expansion and exploration. The subjugation of native populations, the stripping of the land for mining, and the slaughter of the great bison herds were among the nature vs. nationhood issues that took hold as the 1800s progressed.

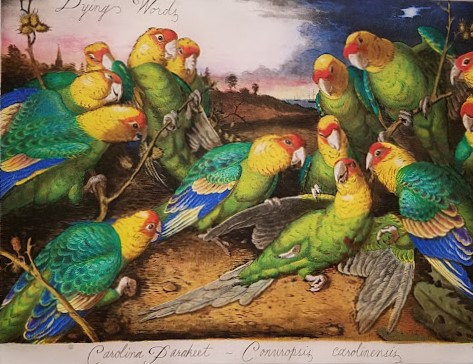

Extinction of species was a new concept then that has become a widely-accepted environmental prerogative in our time. Walton Ford’s 2005 depiction of the death of a Carolina parrot is humorous while at the same time making a searing statement about the extinction — by the early 1900s– of the only native parrot in the US.

Referencing knowledge of the species’ communal behavior, Ford’s composition refigures The Death of General Wolfe, a history painting by Benjamin West. In Dying Words, a similar array of parrots gather around a single mortally-wounded bird to bear witness to its dying words.

Dying Words, 2005

The Death of General Wolfe, 1770

Although occasionally bordering on preachy, the curatorial narrative in the exhibition provides a way to see, where turning a blind eye might be more comfortable.

For three centuries America’s relationship with the environment has been fraught with self-righteousness and naiveté, but inevitably awareness begets change, albeit often at a snail’s pace. All the while artists add their voices to the conversation. So too does Nature’s Nation.

View in Central Park, New York City, 1858

Nature’s Nation: American Art and Environment

On through September 9, 2019

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

Bentonville, AR

479-418-5700

Featured Top Image: In Fallen Bierstadt (2007), on the left, Valerie Hegarty (b.1967) questions the way traditional landscape painting idealizes nature as an untouched retreat, urging us to consider nature as something real and fragile. On the right is the Bierstadt (1830 – 1902) painting that Hegarty referenced, Bridal Veil Falls, Yosemite (c.1871-1873). At the time it was painted, it’s likely this was pretty much as it looked.

Read our article about the inimitable Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Discover 1300 US art museums, historic houses, artist’s studios, and botanical gardens at ArtGeek.art. All in one place! Search by location!

Thank you. Love your posts.

Thank you Pat!