Wander waterside pavillions in a wooded Ozark ravine to experience the History of American Art in the Heart of America.

Most of the original art museums in the U.S. can be traced to the late 19th– and early 20th-century expansion of the nation’s industrial economy. Happily, in the tradition of those mega-rich American industrialists who bought boatloads of art and founded great museums – people like Carnegie, Morgan, Gilcrease, and Ringling – laudable art museums continue to be established by philanthropic business leaders today.

For example, two Los Angeles art museums — The Broad (2015) and the Broad Contemporary Art Museum (2008) on the LACMA campus — are a result of the philanthropy of Eli Broad, the founder of two Fortune 500 companies.

We recently visited another newer art museum that was built upon a commercial fortune. The spectacular Crystal Bridges in Bentonville, Arkansas is the realization of a dream for Alice Walton, daughter of Walmart founder Sam Walton.

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville AR

Temporary exhibition wing, Main Lobby and Restaurant bridge

Opened in 2011, Crystal Bridges is distinguished from America’s iconic older museums in one notable way. Rather than holding collections amassed through travels in Europe and Asia, the Crystal Bridges collection is exclusively focused on American art — be it Early, Modern or Contemporary. American subjects by American artists.

Attention Walmart Shoppers

Even if you’ve never set foot in a Walmart store – the Walton family “welcomes all to celebrate the American Spirit in a setting that unites the power of art with the beauty of nature.”

The tale is told that as a child Alice Walton had passion for art. But growing up in northern Arkansas, “with no major museums nearby, Alice’s access to great original works of art was limited.”

Years later, with the extraordinary financial resources now available to her, she became the driving force behind the founding of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, fulfilling her desire to provide future generations what she had not had — the opportunity to be exposed to great art.

Alice chose a 120-acre wooded ravine in the heart of Bentonville as the setting, and — because of his proven ability to integrate a building into its landscape — she selected Moshe Safdie to design the museum.

An existing creek was channelized with a series of weirs to create ponds, with pavilions nestled along the east and west banks connected by two enclosed glass-walled bridges. The complex is made up of eight buildings, each overlooking the surrounding water and landscape. Local materials were used throughout.

This is the ceiling of the Restaurant bridge.

As first-time visitors, the Main Entrance seemed confusing and not terribly inviting. But once we realized that the front colonnade is on the hillside above the museum we began to get our bearings. When we got hold of a floorplan, the logic of the curved structures, how they’re linked, and the organic beauty of the architectural plan was made clear.

A great way to get a sense of the place is to pass through the coffee bar (we grabbed a coffee as we went) into the restaurant seating area and, ground plan in hand, enjoy views of the pond and flanking pavilions.

Before we leave the subject of architecture: Since 2014, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Bachman-Wilson House has been located on the grounds of Crystal Bridges. Repeatedly threatened by floodwaters in its original location in Millstone NJ, the house was dismantled piece by labeled piece, shipped 1,235 miles in two tractor trailers, and meticulously re-assembled on a thoughtfully-selected plot here. The ground floor of the compact house can be toured by ticketed reservation.

Crystal Bridges’ permanent collection spans five centuries of American art. It is augmented by loans from other museums to provide a complete tour of American art history from colonial times to the present – with a handful of ancient indigenous objects added to the mix. The collection is shown in three distinct parts: Early American Art (meaning everything before 1910), Modern Art, and post-war Contemporary Art.

Sculpture is shown in the galleries and along more than four miles of outdoor trails.

Early American Galleries

The first gallery – We The People — greets us with an array of portraits of Americans who came before — from one of the earliest examples of Jewish portraiture in Colonial America, to Native men and women, to civil rights activists, to children. The portraits introduce us to the real people of American history, spanning time, geography, and social position to remind us of the breadth of experience and aspirations of Americans past — and present.

After the portrait gallery, the Early American Galleries present the works chronologically, setting out themes that track America’s social development.

Written in both English and Spanish, adjacent information panels provide excellent educational and entertaining context to enhance appreciation of the art.

For example, in the section of works produced up through the 1840s, the text accompanying a painting by James Wooldridge (c. 1635 – c.1695) Indians of Virginia (c.1675) tells us: “European artists often presented the rituals, food, and accessories of Indigenous peoples as exotic and mysterious, but also reassuringly familiar. In this painting, the artist used classical poses for the figures, and emphasized a complex and sophisticated culture with organized religion and agriculture that was relatable to Europeans.” That’s the educational part.

The text continues, telling us that the artist spent his entire career in London and thus never actually saw a Native American himself! This painting was a product of his imagination and a composite of several 1590 engravings — that had been brought to England — of Carolina Algonquins.

The works in a section titled In Search of the Spiritual show various paths taken by artists seeking the divine and mystical. In the 19th century, America was considered by writers and artists to be the new Eden, its natural beauty and abundant resources being evidence of God’s favor.

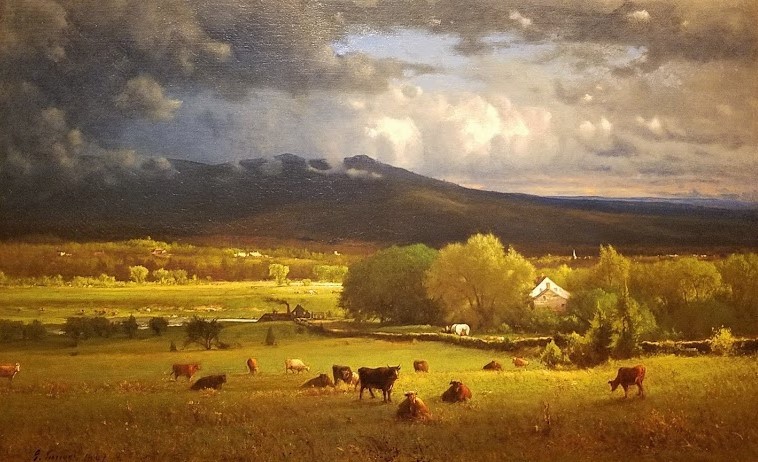

George Inness believed there was a direct correspondence between the natural and spiritual realms, as the Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772) had posited. Inness hoped that “by showing the drama and dynamism of nature, his paintings would transport viewers to a higher emotional or mental plane.”

Before moving on to Modern art, one final gallery considers the Painters of Modern Life (1870s-1910). Works here are grouped thematically: Labor and Leisure, Notions of Beauty, and Nostalgia.

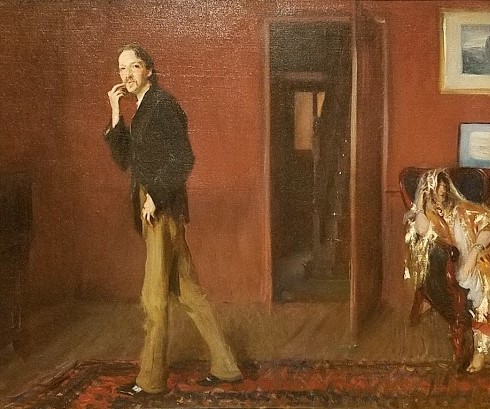

In the Labor and Leisure group we were attracted to a unique and rather awkward composition by John Singer Sargent. Not a posed portrait, it looks rather like a candid “shot” of Robert Louis Stevenson and his wife, Fanny.

Robert Louis Stevenson & His Wife, 1885

“It looks damn queer as a whole.”

Stevenson said of this painting, “It is, I think, excellent, but it is too eccentric to be exhibited. I am at one extreme corner, my wife in this wild dress and looking like a ghost, is at the extreme other end. All this is touched in lovely, with that witty touch of Sargent’s; but of course it looks damn queer as a whole.”

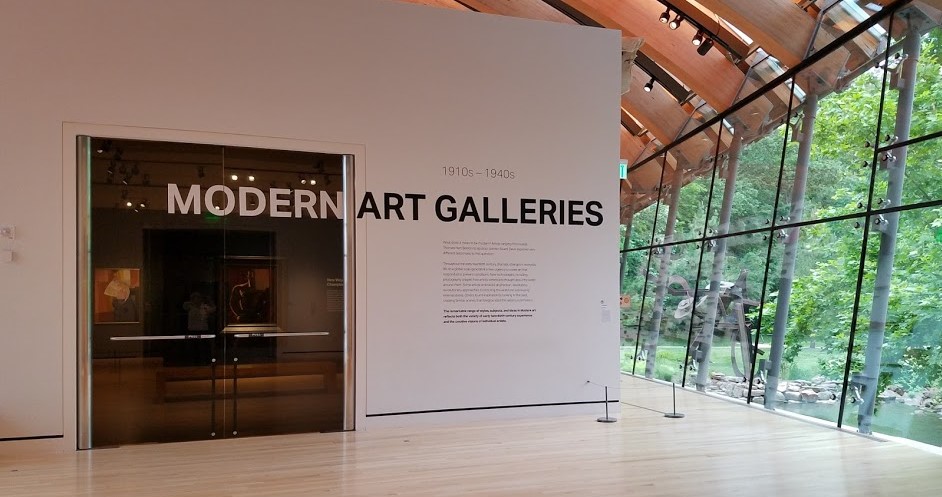

Modern Art Galleries

Throughout the early 20th century, unprecedented changes took place in everyday life across the globe. Artists felt urgently compelled to create art that responded to and reflected the political and social conditions of the times. As they challenged past conventions, a remarkable range of styles, subjects and ideas emerged in Modern art.

Two gallery “boxes” run down the center of the bridge. While the enveloping space is filled with natural light and views of the natural beauty outdoors, controlled lighting in the galleries creates an optimal art-viewing environment.

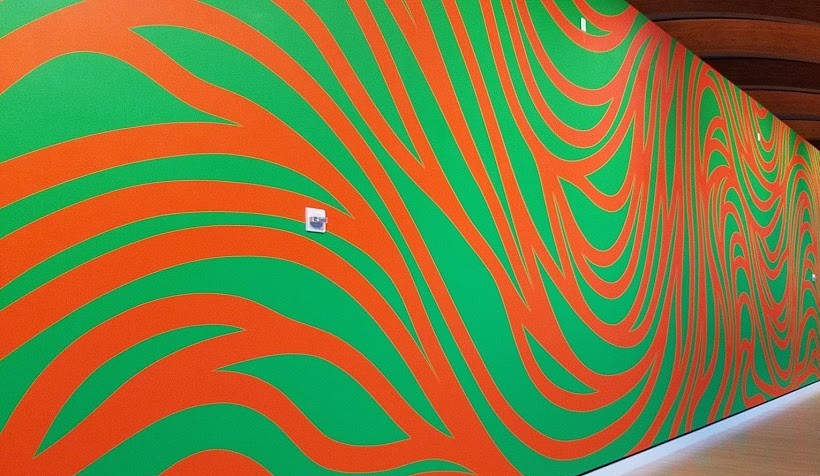

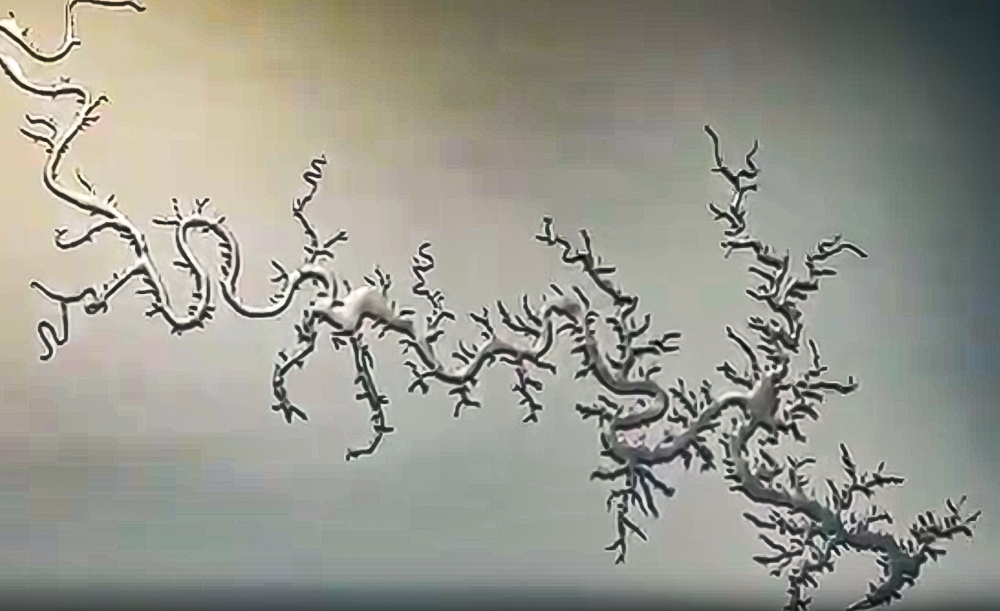

Easy to miss because they are on the outside walls of the gallery “boxes” are some larger pieces. On one wall is Sol Lewitt’s Wall Drawing #880. On another is a graceful meandering construction of recycled silver by Maya Lin. Lin is the artist who became widely known — while she was still an architecture student — for her winning design for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington DC.

Maya Lin (b.1959)

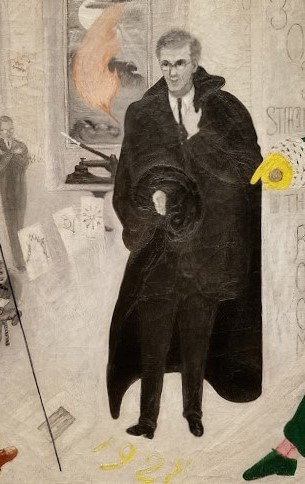

Florine Stettheimer (1871-1944)

But inside the box … ! New ways of seeing; “the familiar and the strange” — figural scenes of modern daily life; and abstraction. The signage here is terrific — as it is throughout the museum — enhancing appreciation of the collection and of individual works.

Many of the works in the Modern galleries are from the Alfred Stieglitz Collection. After Steiglitz’s death, 101 objects were donated to Fisk University in Nashville by his wife, Georgia O’Keeffe. The collection is now co-owned by Fisk and Crystal Bridges.

Photographer, gallerist, and publisher Alfred Stieglitz was a hugely influential promoter of Modern American art. He nurtured the careers of many artists who worked in radical new styles that led the development of Modern art in the U.S.

Marsden Hartley (1877-1943)

Among the artists he championed were Marsden Hartley, Charles Demuth, Arthur Dove and, of course, Georgia O’Keeffe, the woman who would become his wife — and eventually surpass him in fame.

A pelting rainstorm began while we were in the Modern galleries, prompting an enthusiastic guard to exhort us to step outside the gallery to watch the weather event.

Previously I noted that the setting “unites the power of art with the beauty of nature.” This storm underscored that the reverse is also true, that the setting unites the beauty of art with the power of nature.”

After that excitement died down, we contined into the Contemporary Gallery, where An American Story Unfolds.

Contemporary Art Galleries

Again organized in a thematic chronology, the contemporary works in this collection make out-sized statements of intention and visual aesthetics. Working forward from the 1940s into the 21st century, the curation touches on issues of philosophy, politics, mediums, and experimentation.

Organized around Defining an American Voice; The Changing Human Shape; Prosperity and Popular Culture; Artistic Expression and New Technology; and New Histories, New Voices, the signage in the gallery presents a history lesson interpreted through the sensibilities of artists of the time.

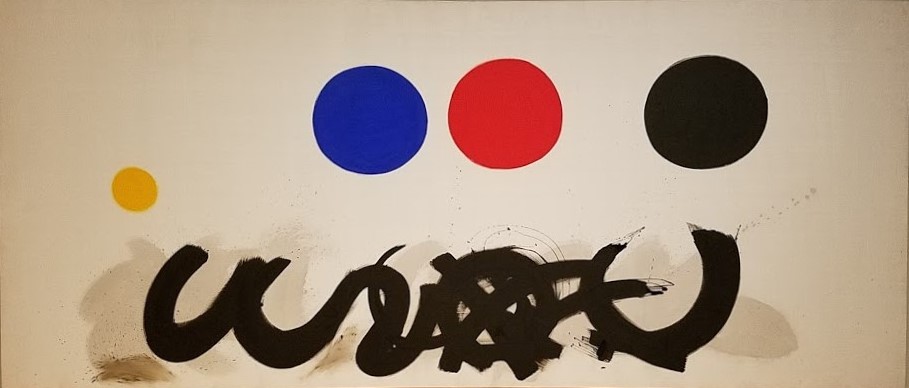

We were immediately attracted to the simplicity of Abstract Impressionist Adolph Gottlieb’s Trinity. This is a classic example of his “Burst” paintings, in which the canvas is divided into an upper and lower zone, with one or more solid-colored orbs hovering above a gestural splash of (usually) black calligraphic energy. By 1950 Gottlieb had observed that the “all-over painting” approach had become a cliché for American abstract painting.”

Trinity, 1962

Another classic example of an artist’s oeuvre in the Crystal Bridges collection is Richard Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park #48. Diebenkorn began his artistic career as an abstract expressionist, although by the mid-1950s he was working in a more figurative, representational style. But in the ’60s he returned to abstraction.

Richard Diebenkorn (1922-1993)

It is for this distinctly personal, geometric style — known as his Ocean Park series — that he is most famous. The Crystal Bridges piece is one of some 135 Ocean Park paintings that he produced over the course of the following two decades.

Art critic Michael Kimmelman once wrote that Diebenkorn’s “deeply lyrical abstractions evoked the shimmering light and wide-open spaces of California.” Gazing at Ocean Park #48, we had to agree.

Kerry James Marshall sees the world as much less light-filled and wide-open. “Our Town is part of his Garden Project series, in which low-income housing projects are ironically rendered as idyllic places.” It takes but a moment to notice the graffiti and other frictions strewn across the crisply-painted houses and manicured lawns. The ajacent text suggests that, “with deep black paint and minimal shading on the figures,” Marshall “emphasizes the blackness of his subjects in an art world that notably lacks images of African Americans.”

Kerry James Marshall (b 1955)

The final text in the Contemporary galleries left us with this: “In the late twentieth century, technology, globalism, and diversity merged on the international superhighway. Art reflects the resulting diversity of artists’ heritage, the variety of materials used, and the range of topics addressed.” In the end, often, “the meaning is open-ended, encouraging viewers to freely interpret the artwork.”

Unfortunately, the wet weather that day interfered with our plan to explore the grounds and to wander to the North Forest to see the outdoor Color Field exhibition that had just opened. (On through September 30, 2019). Our interest in the sculpture exhibit had been piqued by the hand-out booklet, which presents the history of color theory in graspable terms and provides an identification map of the works.

Despite that disappointment, we’d had a stimulating, rewarding day.

We first took in the current special exhibition, Nature’s Nation (on through September 9, 2019) (Read our blog review). Then we enjoyed a pleasant lunch in the Eleven Restaurant, followed by a self-guided tour of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Bachman-Wilson House. The remainder of our time was spent in the galleries — for a total of almost five hours at Crystal Bridges — without exploring the vast grounds!

We’ve been surprised by how many art geeks have never heard of Crystal Bridges or don’t realize what an exemplary museum it is. Is it discounted because it’s in Arkansas? Or perhaps because it’s associated with Walmart? Oh, those pesky pre-conceived notions!

This is a museum that is well worth a trip. Note that Bentonville is just a two-hour drive from Tulsa, which has it’s own art museum gems, the Gilcrease and the Philbrook!

Hmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a little trip?

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

600 Museum Way, Bentonville, AR

479-418-5700

MUSEUM HOURS:

Sat | Sun: 10AM-6PM

Mon: 11AM-6PM

Wed | Thu | Fri: 11AM-9PM

Tue: Closed

The Frank Lloyd Wright Bachman-Wilson House is open for timed-ticket tours during museum hours. Self-guided and audio tours are free while there is a charge of docent-led tours.

Cystal Bridges trails and grounds are open from sunrise to sunset daily and during museum hours.

Ticketed special exhibitions are FREE for members

and youth aged 18 and younger.

Discover 1300 US art museums, historic houses, artist’s studios, and botanical gardens at ArtGeek.art. All in one place! Search by location!

Your articles are awesome.