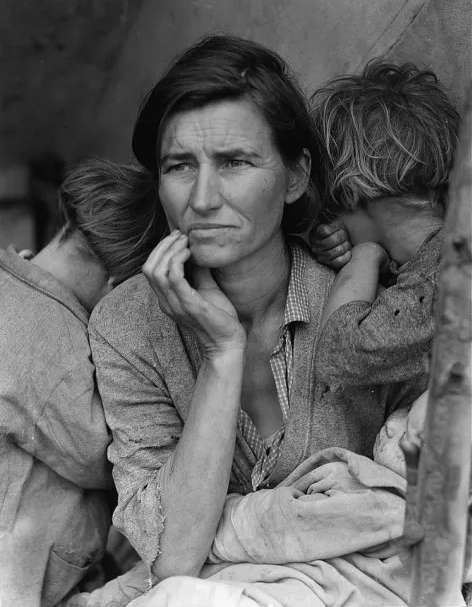

The powerfully moving and iconic photograph, Migrant Mother (below), is the one image most people see in their mind’s eye when they think of Dorothea Lange. That was certainly true for me. But then I had the good fortune to spend time with dozens of her ground-breaking images, all equally eloquent and poignant, at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC.

Now I have a broader knowledge of her work and a deeper feeling for the compassion that drove her to record on film the destitution of displaced and impoverished Americans in the 1930s and ‘40s.

While she vividly captured the devastating hardships endured by certain segments of our society in the second quarter of the 20th century, she did so respectfully, humanizing her subjects, revealing their character and resilience. Almost a century later, our perception of the reality of those hard times is altered as we view these images.

White Angel Breadline, 1933

Child Living in Oklahoma City Shacktown, August, 1936

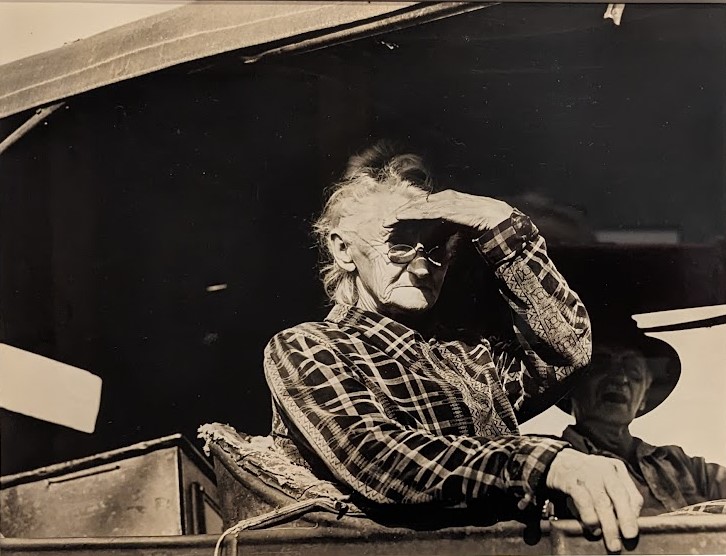

Eighty-year-old woman living in squatters’ camp on the outskirts of Bakersfield CA. November, 1936

.

Dorothea Lange: Seeing People is at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC through March 31st, 2024.

Born on May 26, 1895 in Hoboken, NJ, when Lange was seven she contracted polio, which left her with a weakened right leg and a permanent limp. “It formed me, guided me, instructed me, helped me, and humiliated me,” Lange once said of her altered gait. “I’ve never gotten over it, and I am aware of the force and power of it.”

When she was 12, her father abandoned the family, forcing her mother to move her and her brother from suburban New Jersey to a poorer neighborhood in New York City. She was left on her own much of the time, while her mother worked, and she wandered the streets of New York, fascinated by the diversity of people. She claimed this taught her to observe without imposing, a skill she would later use as a documentary photographer.

Although she’d never used a camera, she knew she wanted to study photography — which she did, at Columbia University, under the tutelage of Clarence H. White. She later apprenticed at several New York photography studios.

In 1918 Lange settled in San Francisco and the following year established what quickly became a successful portrait studio. Hers studio work primarily involved taking portrait photographs of the social elite in San Francisco. In 1920 she married the noted western painter Maynard Dixon, who was 20 years her senior, and together they had two sons.

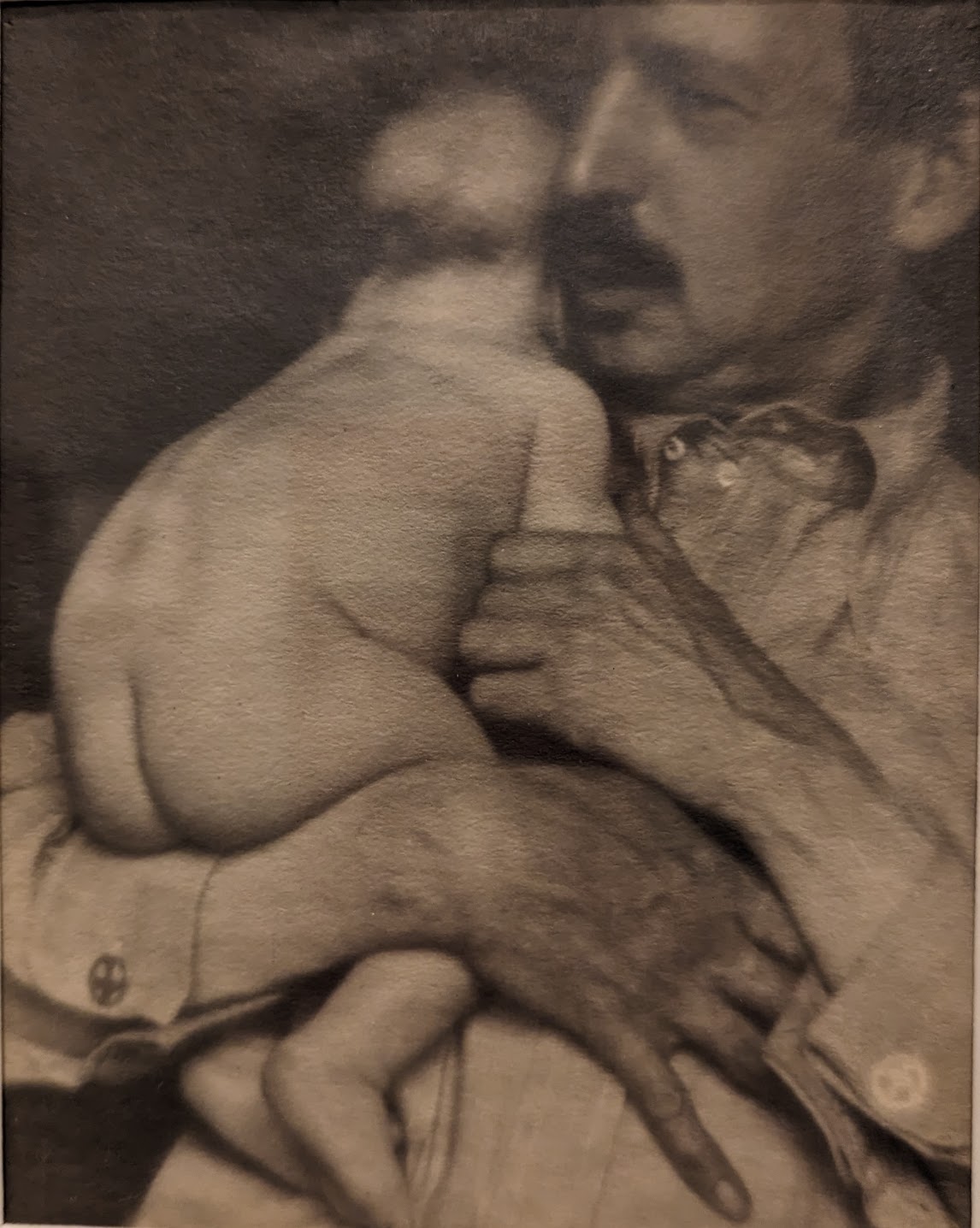

Maynard Dixon and Son Daniel, 1925

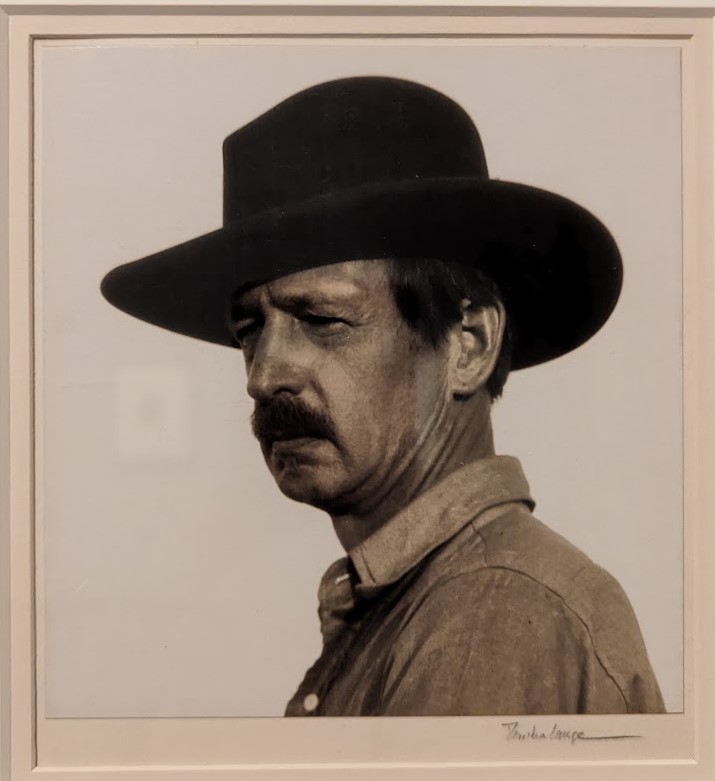

Maynard Dixon, ca.1930

From September 1931 through January 1932 they visited Taos, NM, staying in a home provided by the socialite and philanthropist, Mabel Dodge Luhan. They were embraced by the Taos community of artists and Dixon produced some of his finest work, painting more than 40 canvases. Three years after they returned to San Francisco their marriage ended.

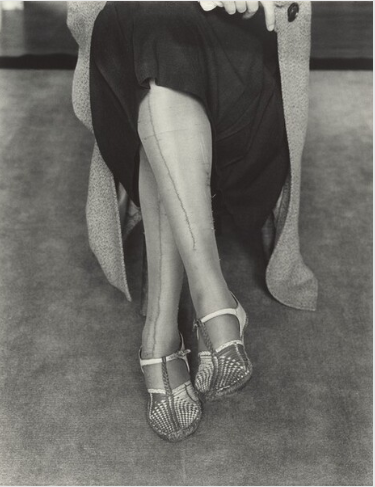

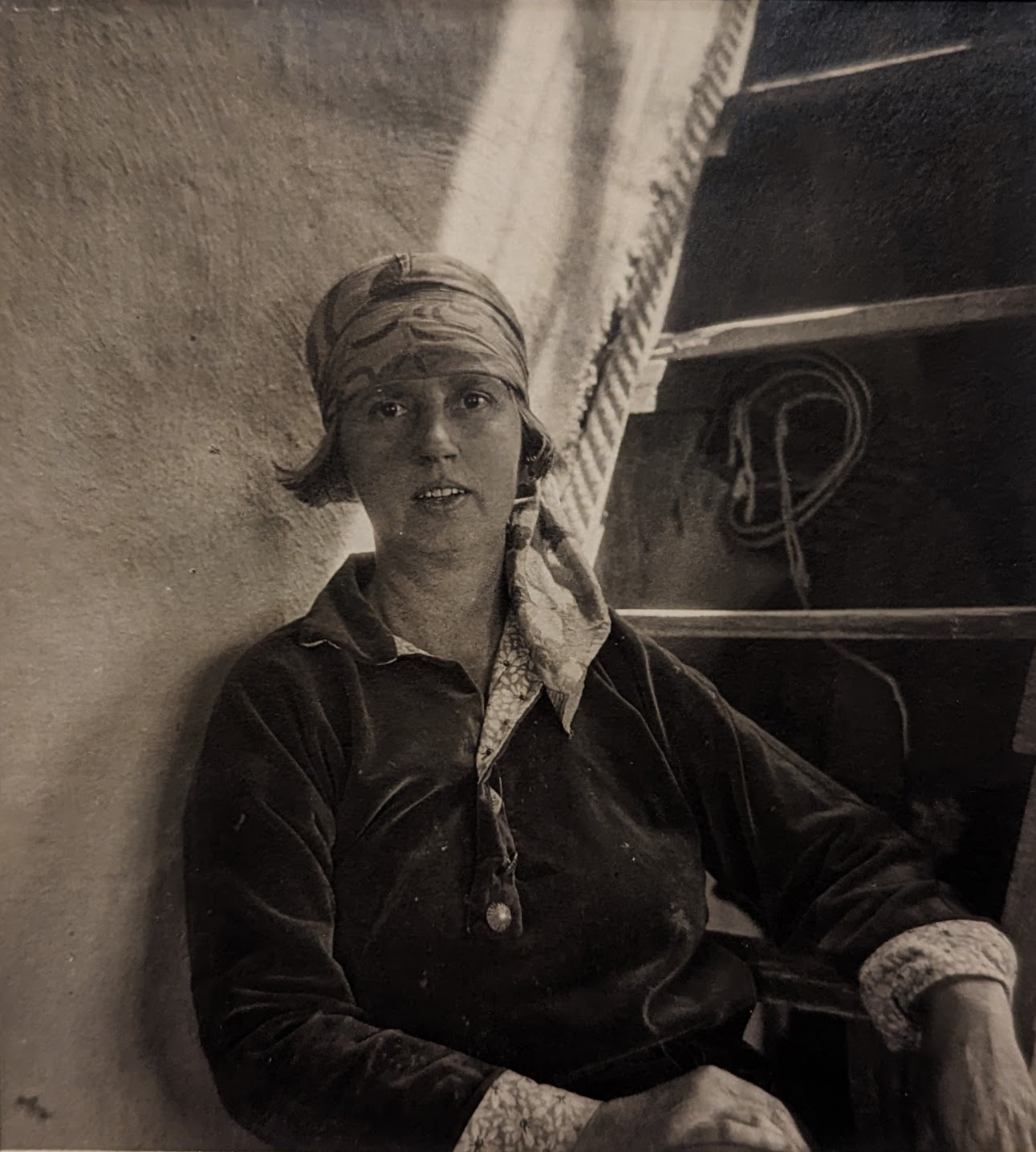

Dorothea Brett, Painter, Taos NM 1931

Mexican American Child, San Francisco, 1928

Lange’s photography studio continued to thrive, but posing the well-heeled for portraits wasn’t enough. With the onset of the Great Depression she began leaving her studio to photograph the homeless men, women and children who were increasingly drifting into California looking for work – which was scarce and paid little.

Author Max Perchick, calling Lange “the greatest documentary photographer in the United States,” wrote that it was in portraying the extent of the social and economic upheaval of the Depression that she found her purpose and direction as a photographer. Her powers of quiet observation and her experience capturing the essence of her portrait sitters gave an intensity to her images for which she quickly became recognized.

Under the heading, Documentary Portraiture, the curatorial text tells us that “Lange’s work during the 1930s synthesized her ideas about portraiture and documentary photography. With new purpose, she used the techniques, compositional strategies, and social skills she had cultivated in her portrait studio to frame the people and events she recorded. By 1940 she had distilled her understanding of documentary photography as an art form that “records the social scene of our time. It mirrors the present and documents for the future.”

Lange talked with her subjects while working, which put them at ease. This engagement allowed her to capture pertinent and personal remarks to accompany the photography, often revealed in the titles of her pictures.

In 1935 Lange was hired by the Farm Security Administration to document the effects of the Depression on the rural poor, and her indelible images—such as the iconic Migrant Mother (1936)—shaped both public perception and government policy.

At a pea-pickers camp in Nipomo CA, Lange noticed a dispirited woman with her children. “I approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding field and birds that the children killed.” Lange took seven exposures of the woman, 32-year-old Florence Owens Thompson, with various combinations of her seven children. The Lange bio on New York’s Museum of Modern Art website tells us that “one of these exposures, with its tight focus on Thompson’s face, transformed her into a Madonna-like figure and became an icon of the Great Depression and one of the most famous photographs in history.”

The bio continues: “On March 10, 1936, two of Lange’s photographs of the Nipomo pea pickers’ camp were published in The San Francisco News under the headline “Ragged, Hungry, Broke, Harvest Workers Live in Squallor [sic].” The photograph that became known as Migrant Mother was published in the paper the following day, on March 11, accompanying the editorial “What Does the ‘New Deal’ Mean to This Mother and Her Children?” The Los Angeles Times reported that the State Relief Administration would deliver food rations to the 2,000 migrants living in the Nipomo camp the next day.

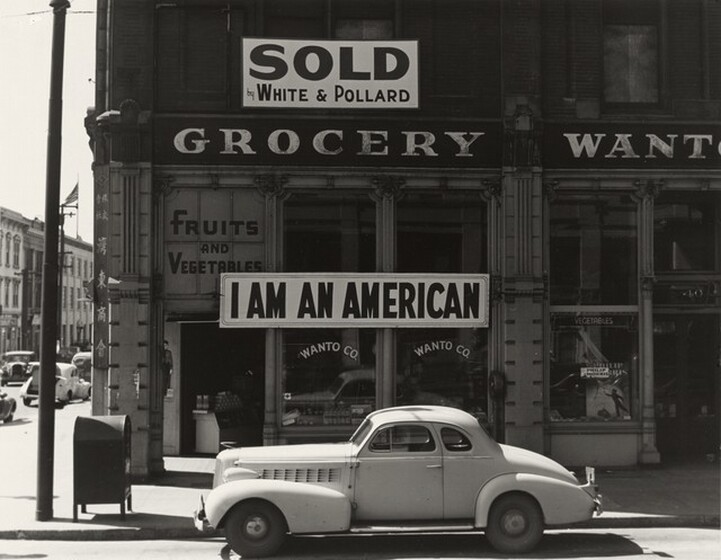

In 1941, Lange was awarded a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship for achievement in photography. But after the attack on Pearl Harbor, she gave up the fellowship in order to go on assignment for the War Relocation Authority to document the internment of Japanese Americans from the west coast of the US. She travelled throughout urban and rural California photographing families leaving their homes and hometowns on orders of the government. 120,00 individuals of Japanese ancestry — the majority of whom were American citizens — were removed to ten inland detention camps.

Grandfather and Grandchildren Awaiting Evacuation Bus, 1942

Japanese American-Owned Grocery Store, Oakland CA, 1942

Fearing that the images would elicit too much sympathy, the WRA did not release the photographs until after the war.

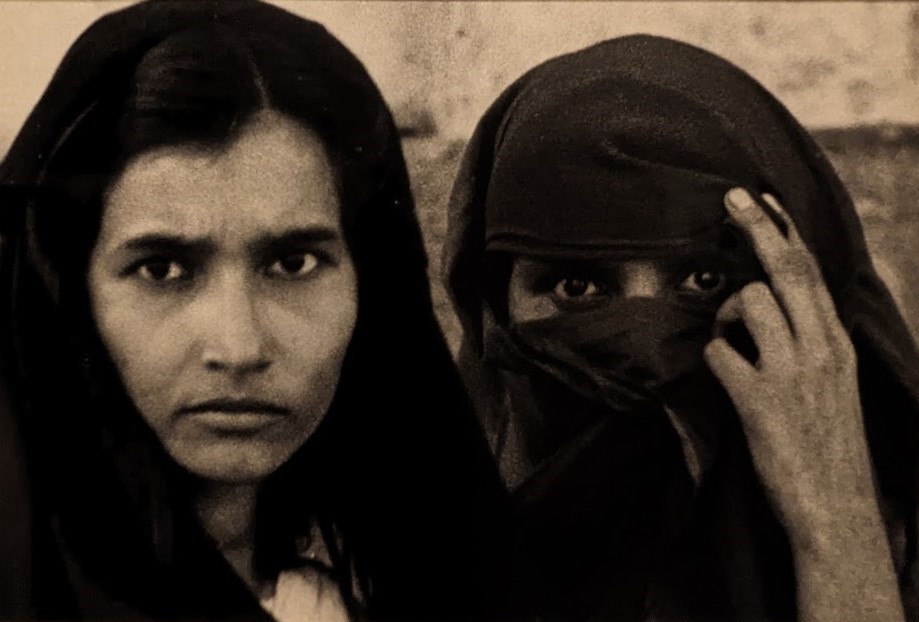

Lange began working internationally in 1954. Her second husband, Paul Taylor, began consulting on international economic development for the US State Department and, in 1958, they travelled abroad for eight months, visiting Korea, Indonesia and Vietnam. In the early ’60s they travelled to Egypt and Venezuela. Her health was declining, but she continued to concentrate on portraiture, capturing a new sort of beauty and serenity in these foreign environments.

Eqypt, 1963

Curatorial text adjacent to this image says, “Working in Egypt proved both stimulating and challenging for Lange, as she periodically experience hostility from locals who found her camera intrusive. […] Lange focused on women and was interested in the social and religious practices that required Muslim women to cover their bodies.”

Dorothea Lange devoted the last years of her life to her family and to organizing a retrospective exhibition of her photographs at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She died in late 1965, after a long battle with cancer.

The roughly 100 images in Dorothea Lange: Seeing People provide insight into the reality of 20th Century American history, powerfully portraying the humanity of the people who lived that history. The accompanying curatorial information provides the context needed to fully appreciate this gifted woman and her extraordinary work.

ArtGeek highly recommends this exhibition.

Hmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a little trip …

Dorothea Lange: Seeing People, on through March 31st, 2024.

National Gallery of Art

4th and Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DC

202-737-4215

Banner image: Paul S. Taylor, Dorothea Lange in Texas on the Plains, Texas, ca. 1935

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the only search engine that makes it easy to discover almost 1700 art museums, historic houses & artist studios, and sculpture & botanical gardens across the US.

Just go to ArtGeek.art and enter the name of a city or state to see a complete interactive catalog of museums in the area. All in one place: descriptions, locations and links.

Use ArtGeek to plan trips and to discover hidden gem museums wherever you are or wherever you go in the US. It’s free, and it’s easy and fun to use!

© Arts Advantage Publishing, 2024

Hey there! I’ve been following your web site for a long time

now and finally got the bravery tto go ahead and give you a shout out

frdom Austin Texas! Justt wanted to tell you keep up

the excellent job! https://bandurart.mystrikingly.com/