How many people – even art geeks like us – can name America’s first museum of modern art? We suspect most would also be hard pressed to say where The Phillips Collection is located! Or where Renoir’s well-known and well-loved Luncheon of the Boating Party hangs.

It was a surprise to us that The Phillips Collection refers to itself as “America’s First Museum of Modern Art” — but given its history, that claim appears to be true! Founded by art collector and philanthropist Duncan Phillips in 1921, The Phillips Collection has been acquiring modern and contemporary art for more than a century. Duncan Phillips’ former home—and additions to it—in Washington’s historic Dupont Circle neighborhood provides a unique setting for the still-growing collection of nearly 6,000 works.

The house at 21st and Q Streets, NW, ca. 1900.

Partial view of museum today

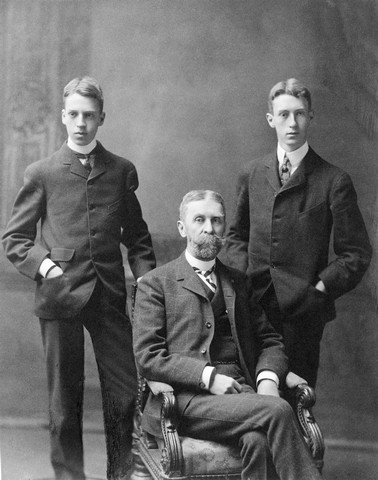

Duncan Phillips (1886-1966) was the son of Major Duncan Clinch Phillips, a Pittsburgh businessman and Civil War veteran, and Eliza Laughlin Phillips, whose father was a banker and co-founder of Jones and Laughlin Steel Company. Duncan and his his older brother, Jim, were so close that Jim postponed starting college for two years so that he and Duncan could attend Yale University together. At Yale, the brothers developed a fascination with contemporary art and, pooling their allowance, they began collecting paintings.

In 1914 the brothers moved to New York City together and Duncan began to write about art, publishing his first book, The Enchantment of Art. Duncan’s passion for art was fueled by friendships with young artists, trips to Europe, and visits to the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1916 the brothers convinced their parents to set aside $10,000 annually to allow them to assemble a collection of contemporary American painting for the family.

Duncan and James Phillips with their father, Major D.C. Phillips, circa 1900. Photo courtesy of The Phillips Collection

Duncan Phillips and his brother Jim, at Yale University. Photo courtesy of The Phillips Collection

We can only imagine Duncan’s grief of losing both his father and beloved brother within one year of each other. To cope with these staggering blows, he turned to the restorative quality of art. “Sorrow all but overwhelmed me,” he later wrote. “Then I turned to my love of painting for the will to live.” He and his mother founded the museum as a memorial, opening it to the public in fall of 1921. In a specially designed room added onto the second floor of the family home, they showed selections from what was then a 237-work collection. The curation reflected Duncan Phillips’ pioneering idea of creating a museum where the art of the past and the present were considered on equal terms.

“A home that had been a place of sorrow became a place to linger and reflect with color, line, and form, to be stimulated by bold ideas and intimate moments, both historical and contemporary, political and lyrical.”

— Alice Phillips Swistel, grandniece of Duncan Phillips

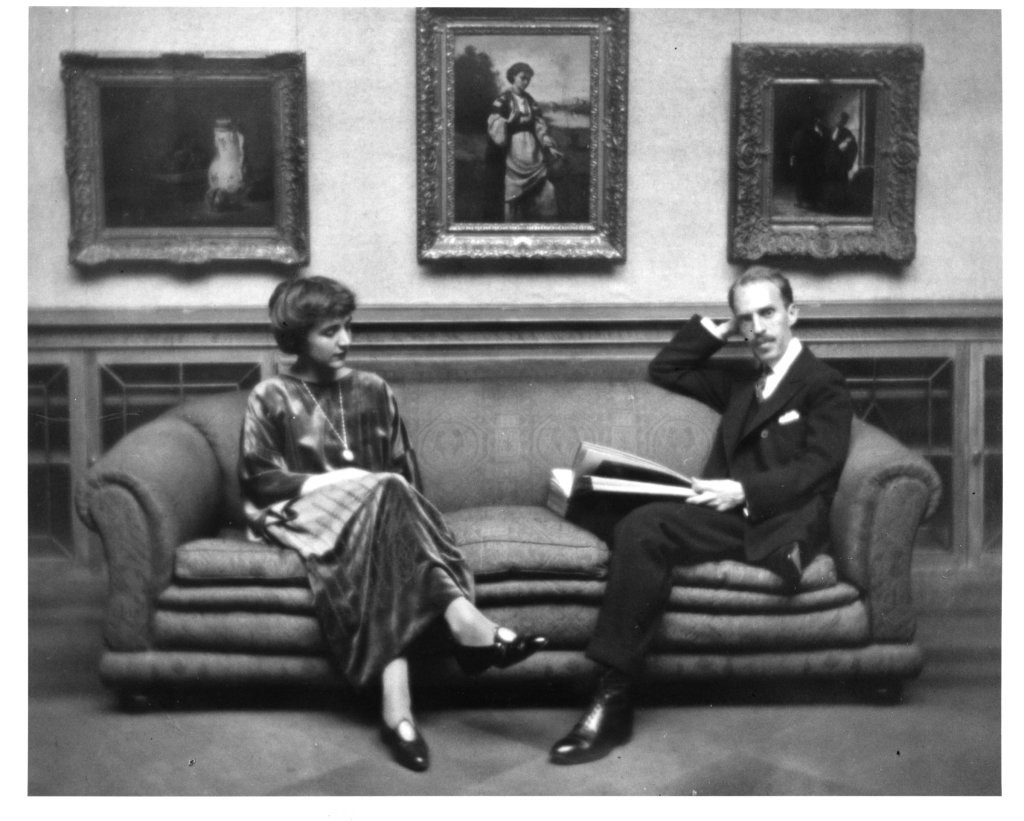

Shortly before the museum opened, Duncan Phillips married painter Marjorie Acker (1894-1985), and she became his partner in developing The Phillips Collection. Having been encouraged to pursue art by her uncles―painters Gifford and Reynolds Beal―Marjorie studied at the Art Students League in New York City. She met Duncan at an exhibition of his collection at The Century Club in New York in 1920. Marjorie painted almost every morning, ran the household, and served as Associate Director of the museum. Over the course of their lifetime together they collected nearly 2,500 works of art. When Duncan died in 1966, Marjorie became the museum director, continuing to develop close relationships with artists and the artistic community of Washington DC.

Marjorie and Duncan Phillips, c. 1920

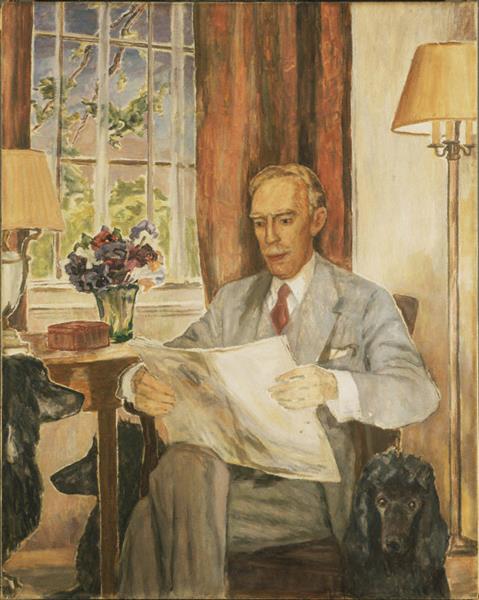

Portrait of Duncan,

by Marjorie Acker Phillips

Self-Portrait, by Marjorie Acker Phillips

By 1930, the collection had grown to such a size that the family moved out of their Dupont Circle home, allowing the entire house to be dedicated to the museum. Thirty years later, a two-story annex was built to accommodate much needed gallery space and a more spacious main entrance. In the years since, continued growth has led to two expansions of the annex as well as the purchase and integration of the apartment building next door, doubling the museum’s footprint to 60,000 square feet.

Over the course of 50 years Phillips built a world-class collection of nearly 2,000 works of modern art of which 1,400 were American, most of them acquired while the artists were alive and actively exhibiting. He chose to collect in-depth the work of some artists — like Milton Avery, Arthur Dove and John Marin — while he selected just one or two exceptional works of others — like Thomas Eakins, Winslow Homer, and Edward Hopper. As a result, the collection of American works is not comprehensive, but it does reveal the changing character of American art in the 20th century.

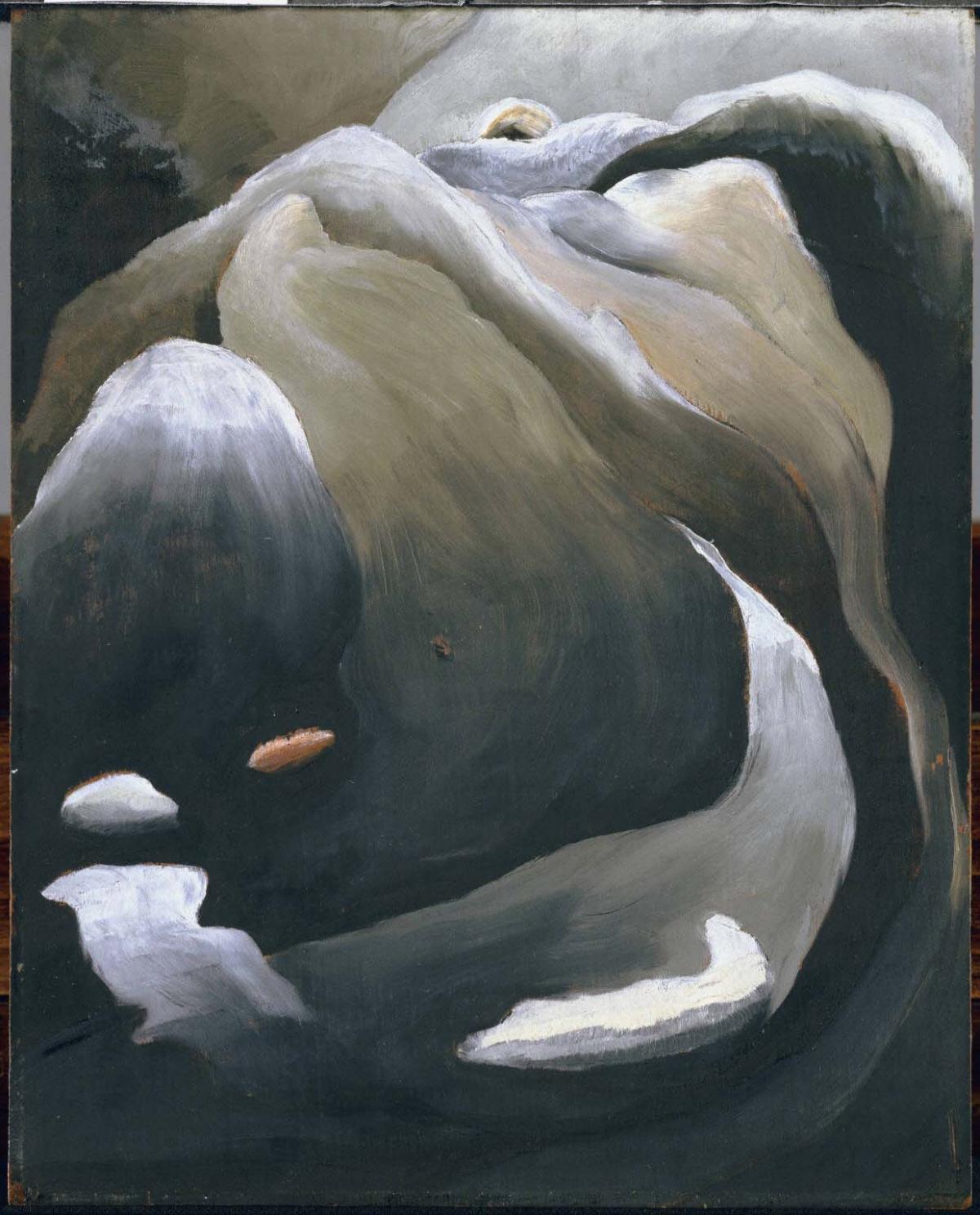

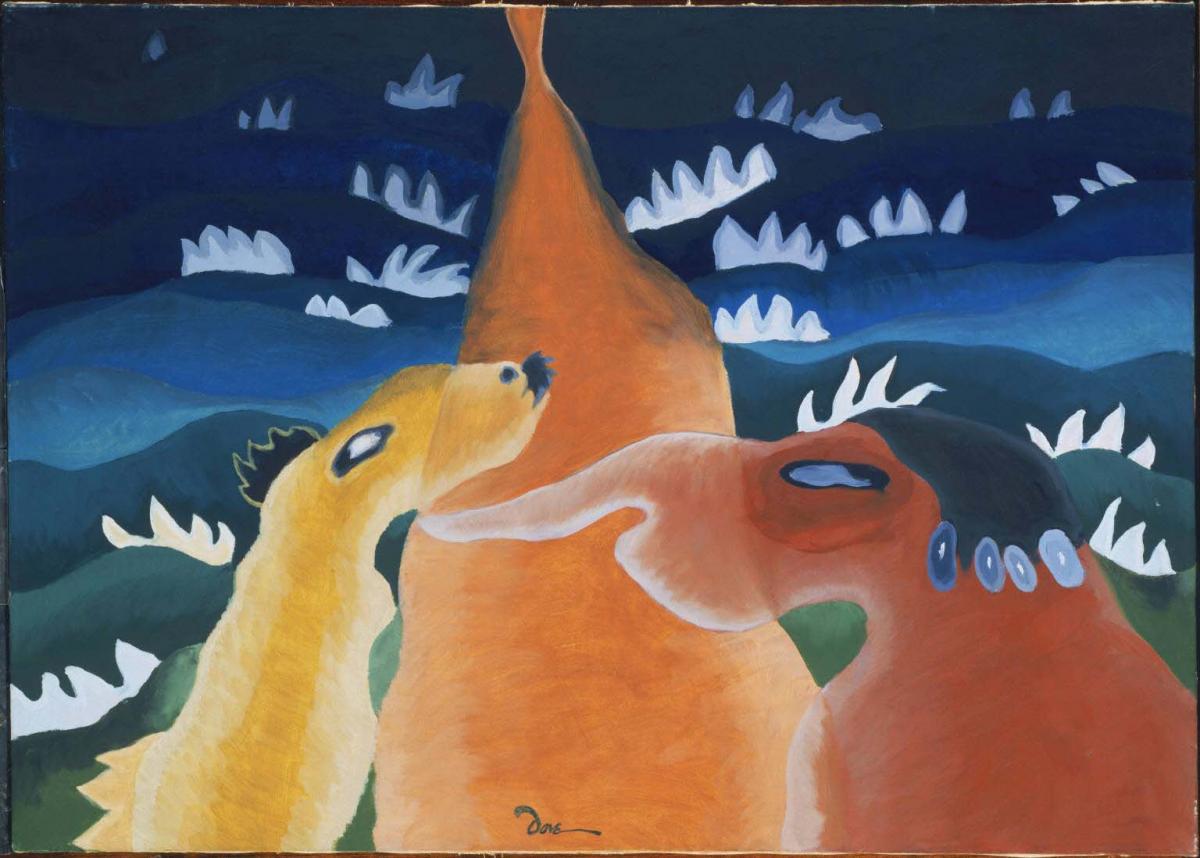

Duncan Phillips was not a timid collector. A post in the Phillips Collection blog tells of the relationship between him, Arthur Dove, and Dove’s dealer Alfred Stieglitz. “Beginning in 1930, museum founder Duncan Phillips (1886-1966) became Dove’s patron. He sent Dove a check for 50 dollars a month (which gradually increased to 200 a month) in exchange for first choice of the artist’s paintings that were exhibited at Stieglitz’s gallery. Phillips responded to Dove’s simple way of life and his independence from European art movements.” The Phillips Collection mounted Dove’s first museum retrospective in 1937 and owns 56 works by the artist—the largest collection of works by Dove in the world.

Arthur G. Dove, Waterfall (1925)

Arthur G. Dove, Tree Trunks (1934)

Arthur G. Dove, Lake Afternoon (1935)

“Dove’s relationship with my father must stand as one of the most interesting and productive artist-patron relationships of modern times . . . Dove was the model of what [my father] wanted most to encourage—the independent artist with a powerful, fresh, and highly personal vision.” — Laughlin Phillips, son of Duncan Phillips

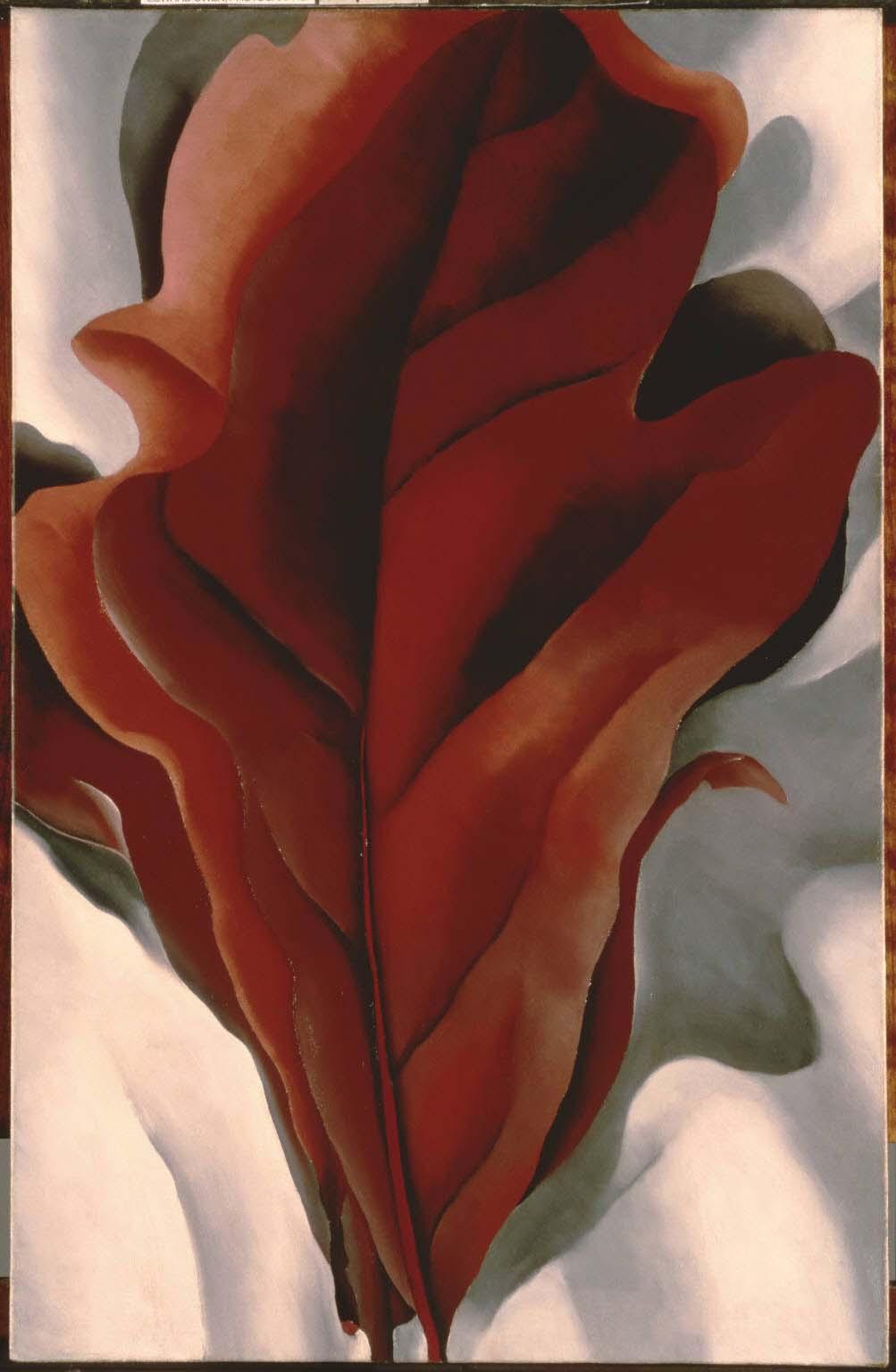

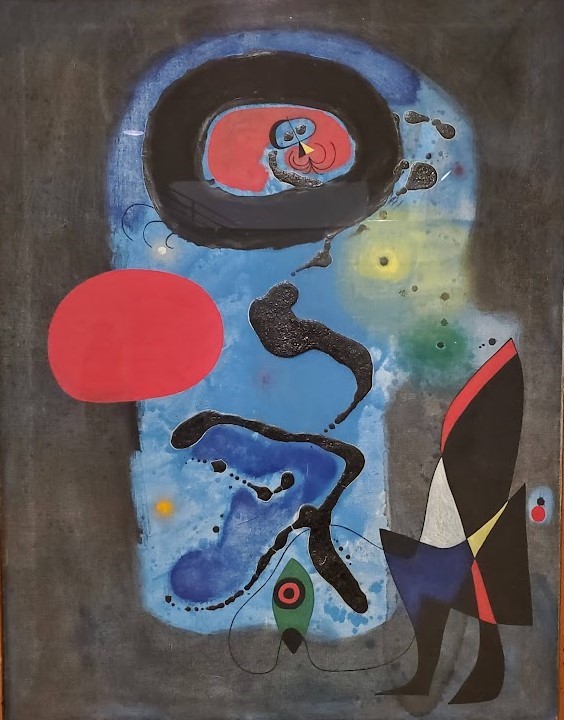

From the outset, the vision for The Phillips Collection was “an intimate museum combined with an experiment station.” As a collector, Duncan Phillips was noted for his willingness to deviate from the museum norm of displaying works together based on shared nationality and geography. He preferred to interpret modernism as a dialogue between past and present. He collected the work of his contemporaries at a time when art that did not follow traditional, academic standards was not widely accepted as aesthetically and culturally valuable. This resulted in Phillips being the first to collect and exhibit artists who were not well known at the time, such as Milton Avery, Pierre Bonnard, Georges Braque, Jacob Lawrence, Grandma Moses, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Rufino Tamayo.

Rufino Tamayo, Mandolins and Pineapple, 1930. Acquired 1930

Georgia O’Keeffe, Large Dark Red Leaves on White (1925). Acquired 1943

Joan Miro, Red Sun, 1948. Acquired 1951

Milton Avery, Pink Still Life, 1938.

Acquired 1943

Maurice Pendergast, Under the Trees, c.1915

Acquired 1921

Our recent visit confirmed that Duncan Phillips’ collecting philosophy continues to this day. He never sought to establish a comprehensive survey of styles or movements. Rather, he looked for what he called “rivers of artistic purpose,” envisioning his museum as a place where the pictures would be allowed to speak for themselves, and he saw the gallery as “a meeting place of many minds, harmonized by a genuine respect for the spirit of art.” The Phillips continues to follow the practice of creating “visual conversations” in the galleries by frequently rotating the works from the permanent collection into new arrangements, often featuring more recent acquisitions alongside older favorites. This encourages the curators to create interesting dialogs about color, form, and narrative between modern and contemporary art.

Left: Frank Stella, Stellar’s Albatross (From The Exotic Bird Series), 1977

Epitomizing that dialogue between past and present, Richard Diebenkorn acknowledged that Henri Matisse’s Studio, Quai St. Michel had been “coming out in his work for decades” after having studied while stationed at Quantico during WWII. He spoke reverently about his visits nearly every weekend to the Phillips which he stated was “a refuge, a sanctuary for me to absorb everything on those walls.” The museum holds two paintings and four works on paper by Matisse, and five paintings and six works on paper by Diebenkorn.

Henri Matisse, Studio, Quai Saint-Michel, 1916, Acquired 1940

Richard Diebenkorn, Girl With Plant, 1960. Acquired 1961

Two rooms dedicated to a single artist have been maintained, although relocated, through the years.

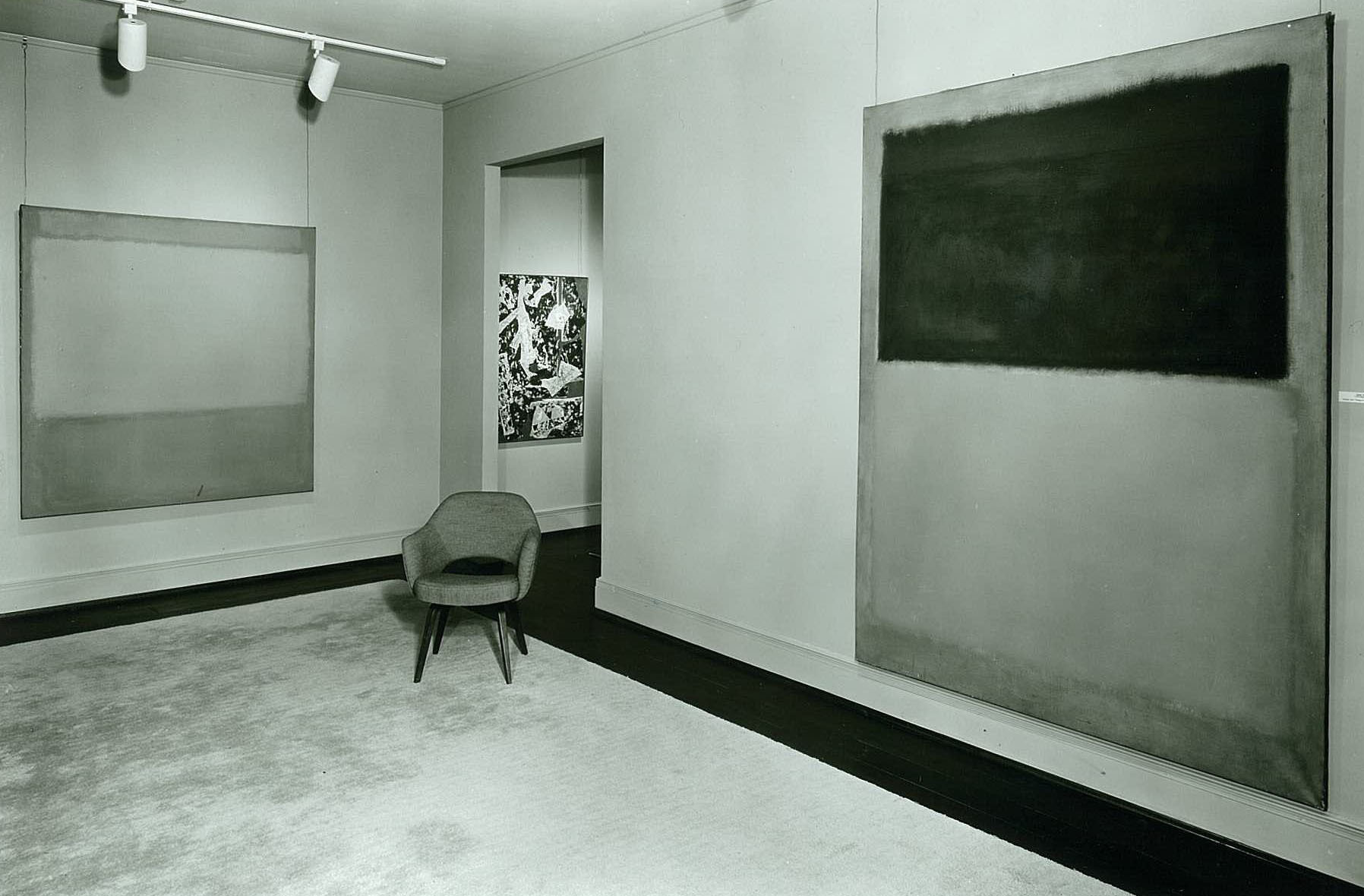

The Rothko room, now on the second floor, is an intimate sanctuary featuring four of the artist’s large color-field paintings. In 1960, as Phillips was working with the architects designing the building expansion, he designated a special room to display Rothko’s paintings. Rothko wished his largest canvases to be installed “so that they must be first encountered at close quarters, so that the first experience is to be within the picture.” With one painting on each wall, low lighting to enhance the resonance of the colors, and a single bench for quiet viewing (and no photography allowed), the room is, as intended, a meditative space. Duncan Phillips referred to it as a “chapel.”

The Rothko Room in 1960 annex

Rothko Room, 2012. Photo: Klaus Ottmann

Duncan Phillips was an enduring supporter of the Swiss-born German artist, Paul Klee. He appreciated Klee’s experiments with surface and texture and his precedent-setting use of banding, central images, and geometric motifs. So much so that Phillips maintained a constant display of Klee’s work over several decades in what became known as “The Klee Room.” From 1948 to 1982, the Klee Room was located in a former sewing room on the second floor of the house. Today, nine of the fifteen Klees in the collection were on display in a “new and improved” dedicated gallery.

The Klee Room, 1963

The Klee Room, 2022

Paul Klee, Arrival of the Jugglers. 1926

Paul Klee, Little Regatta, 1922

There is a third gallery showing the work of a single artist, Jacob Lawrence. In 1942, The Phillips Collection acquired the 30 odd-numbered panels of Lawrence’s powerful narrative, The Migration Series (The even-numbered panels were purchased by the Museum of Modern Art, New York). The series of 12″ x 18″ paintings portrays the movement between 1914 and 1930 of over a million African Americans from the rural South to the industrial North in search of work and a better life. The historical narrative is a sobering reminder of the hardships faced by refugees the world over.

PANEL #1. DURING WORLD WAR I THERE WAS A GREAT MIGRATION NORTH BY SOUTHERN AFRICAN AMERICANS.

PANEL #55. THE MIGRANTS, HAVING MOVED SUDDENLY INTO A CROWDED AND UNHEALTHY ENVIRONMENT, SOON CONTRACTED TUBERCULOSIS. THE DEATH RATE ROSE.

Going to the Phillips is like visiting old friends. Of course, there was Renoir’s The Luncheon of the Boating Party.

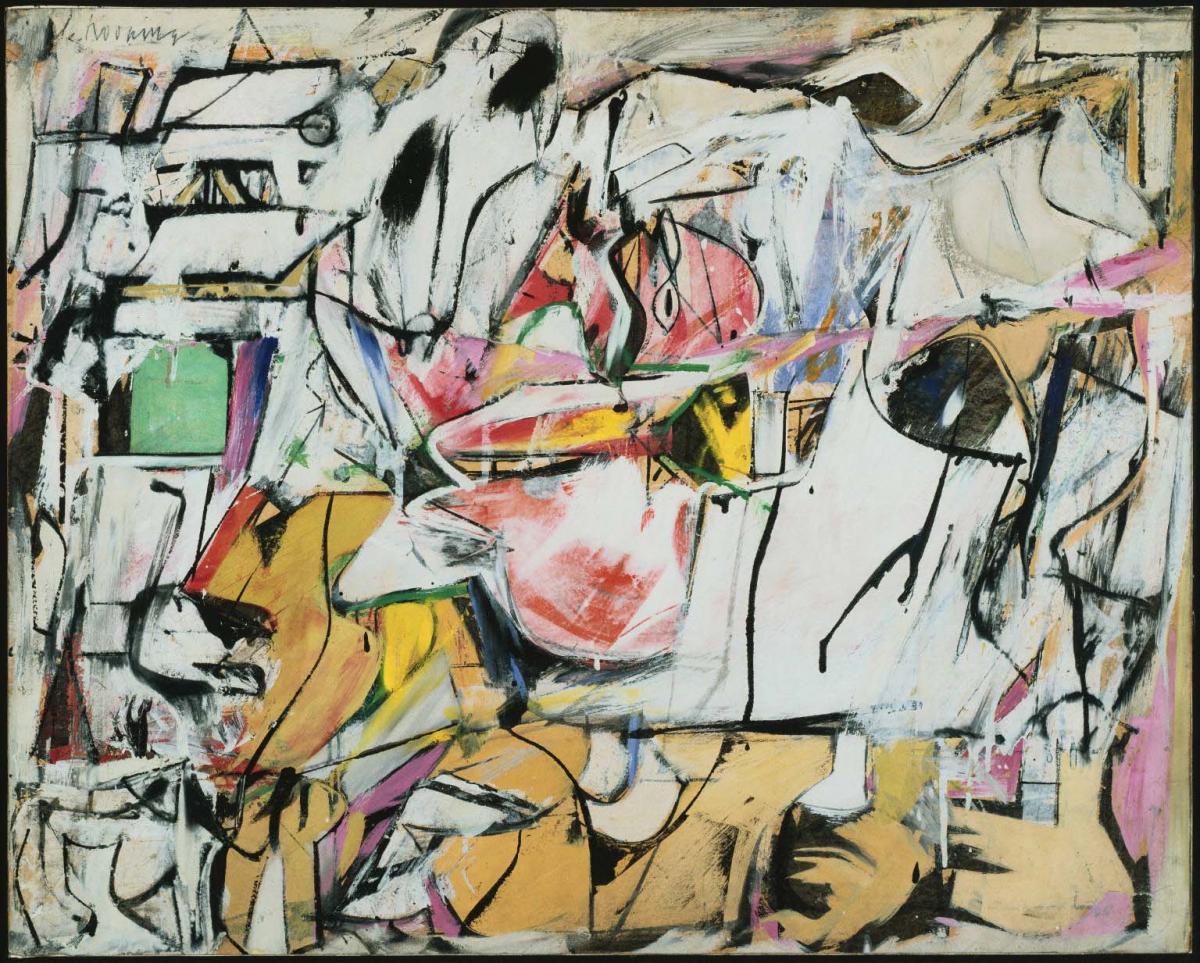

And we encountered Calders, a Lichtenstein, a Mondrian, a couple of Joseph Albers, Bonnards, a Vuillard, a Stuart Davis, a De Kooning …

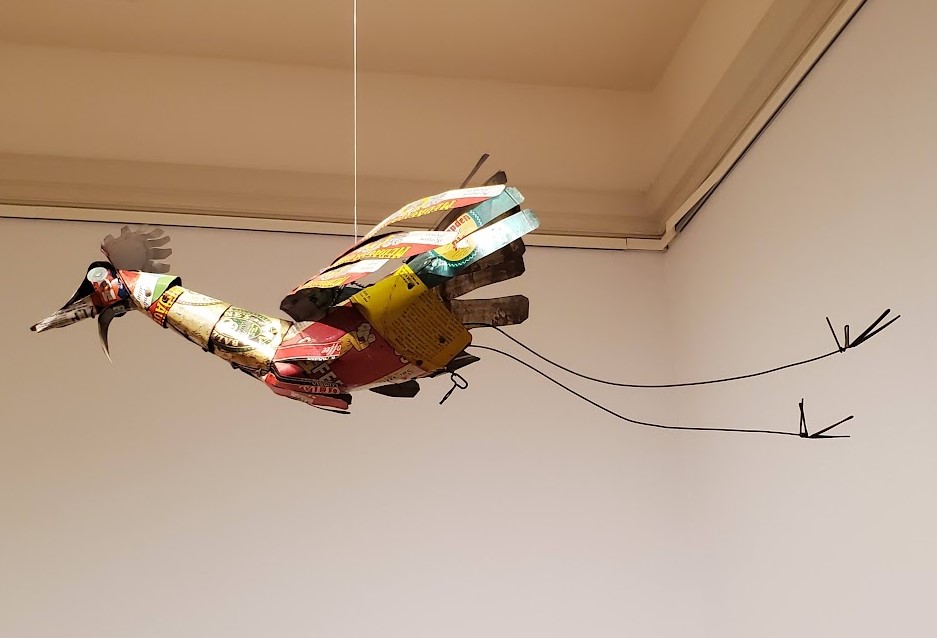

Alexander Calder, Only, Only Bird (1951)

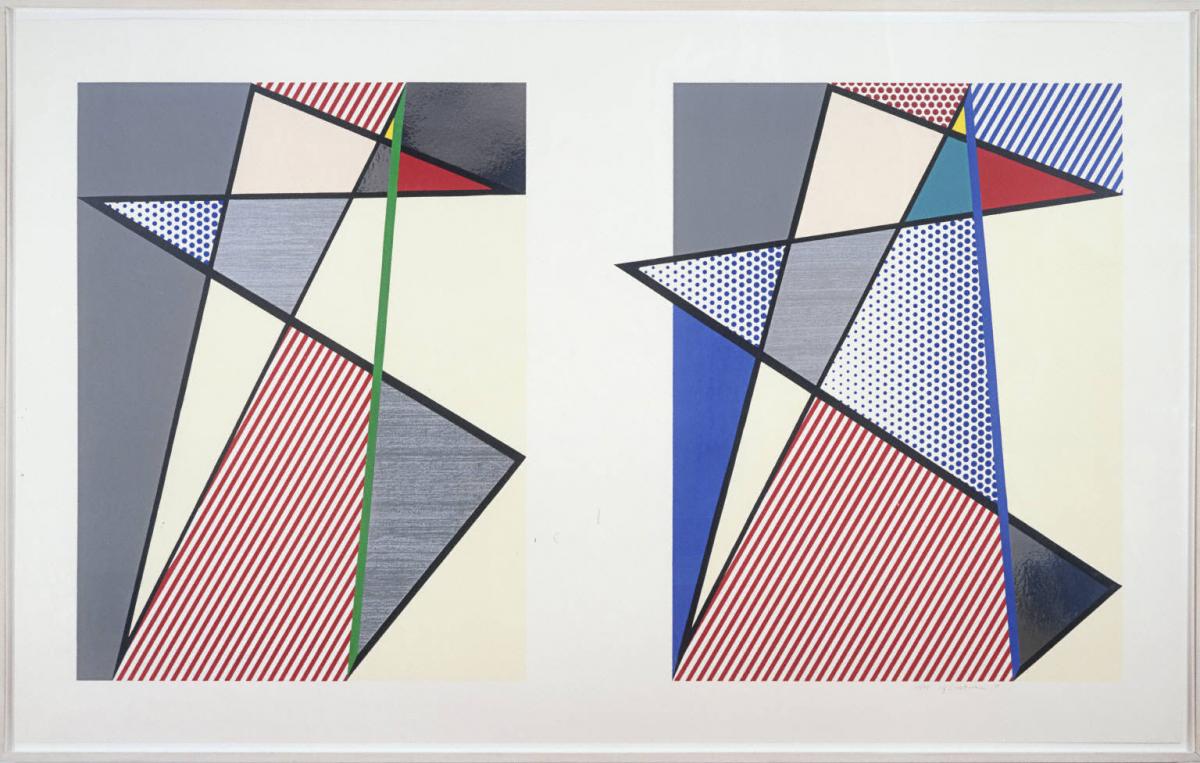

Roy Lichtenstein, Imperfect Diptych (Imperfect series) (1988)

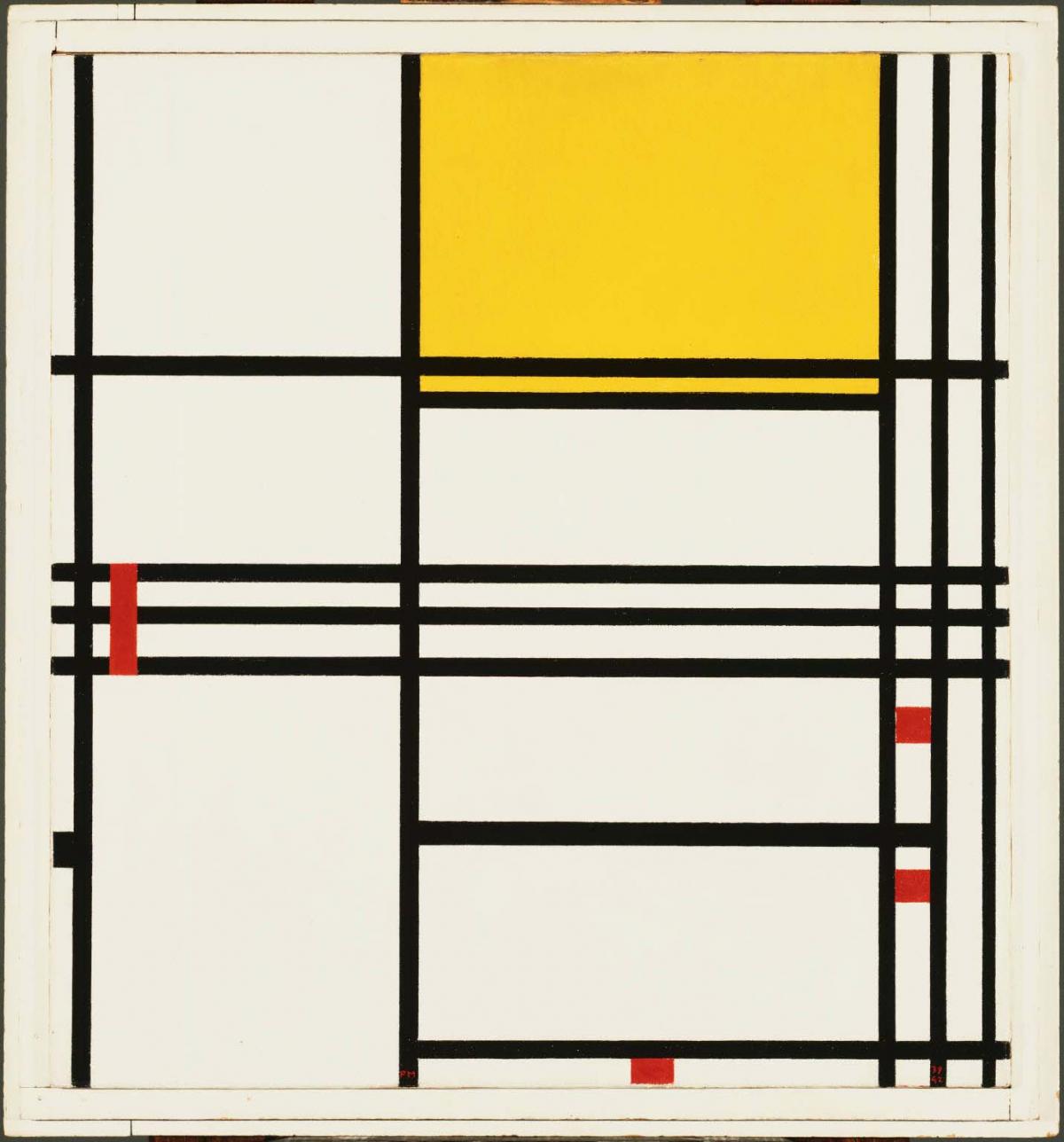

Piet Mondrian, Painting No. 9 (between 1939 and 1942)

Josef Albers, Homage to the Square: Temprano (1957)

Pierre Bonnard, Bowl of Cherries (1920)

Edouard Vuillard, Woman Sweeping (c. 1900)

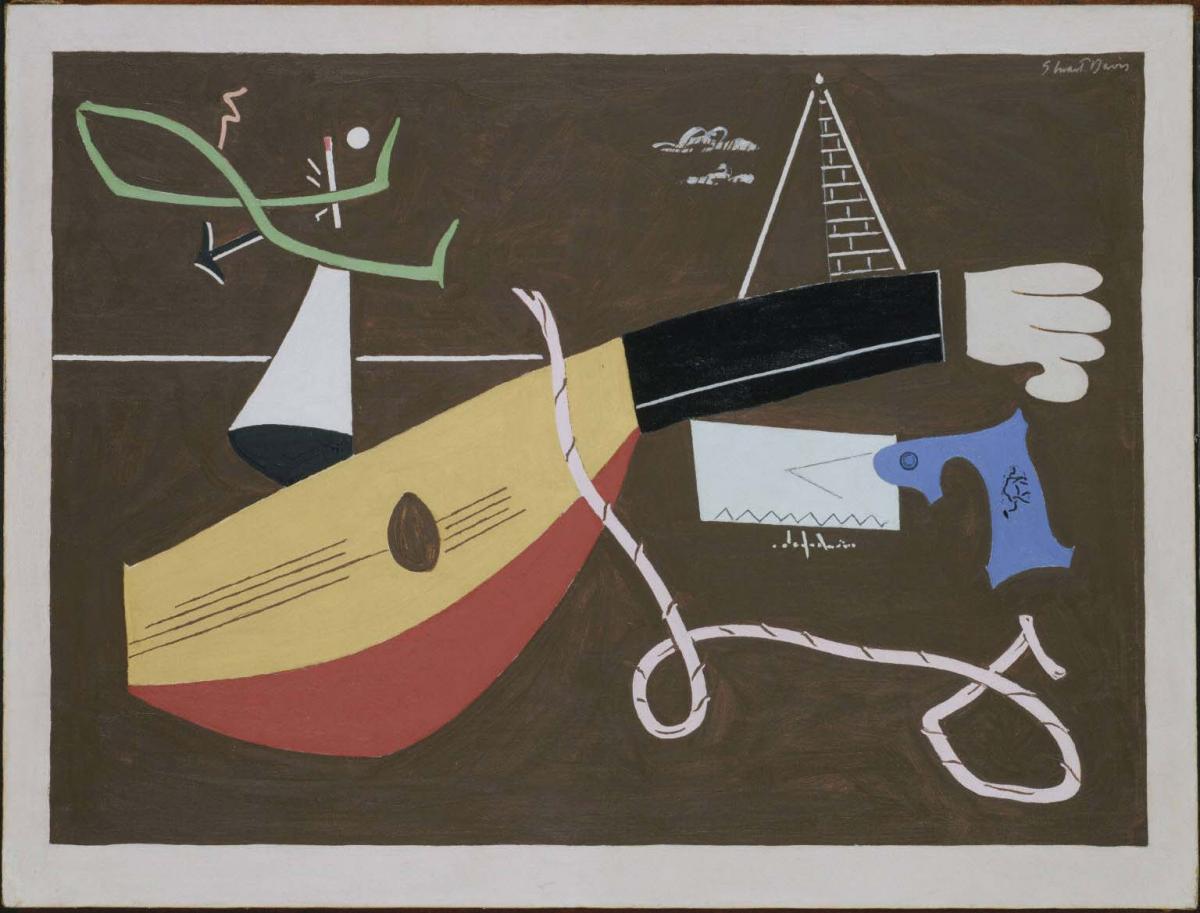

Stuart Davis, Still Life with Saw (1930)

Willem de Kooning, Asheville (1948)

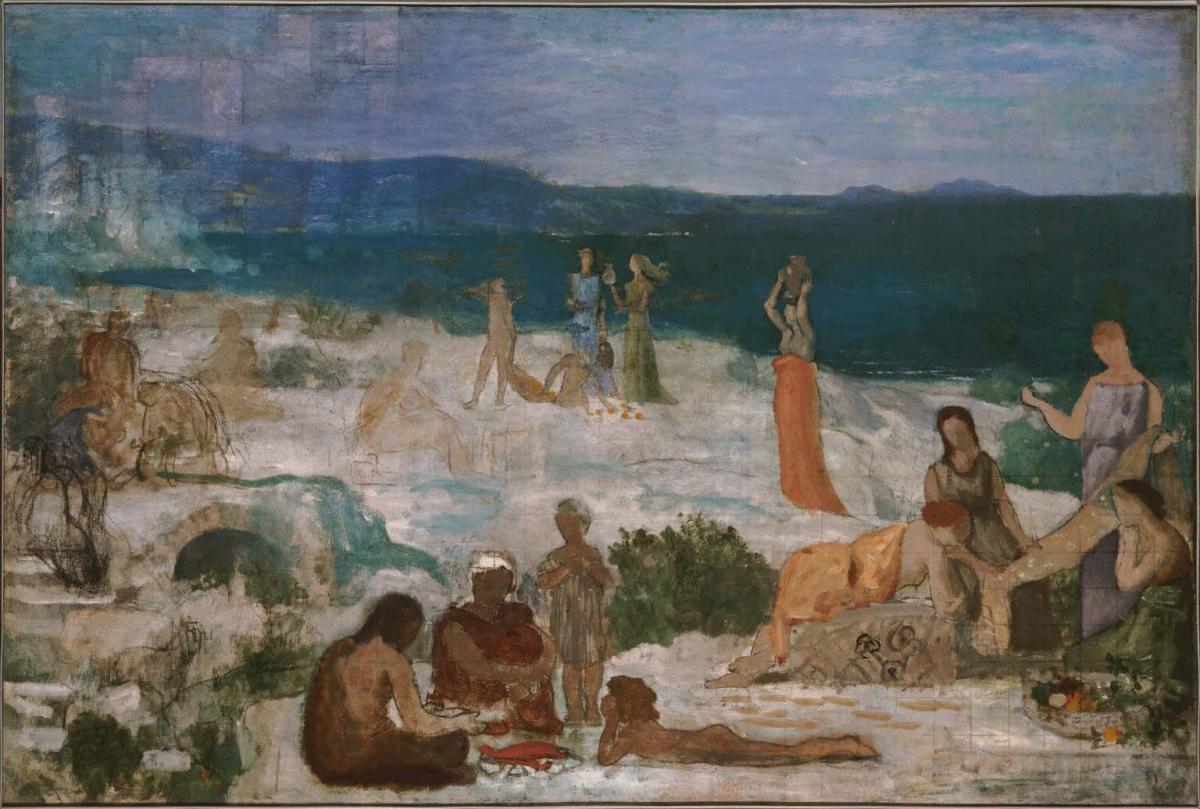

In the oak-paneled Music Room alone were a Gericault, a De Chirico, and two Puvis de Chavannes …

Installation view, the Music Room

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Massilia, Greek Colony (ca. 1868-’69)

Giorgio De Chirico, Horses (ca. 1928)

Theodore Gericault

Two Horses (ca. 1808-’09)

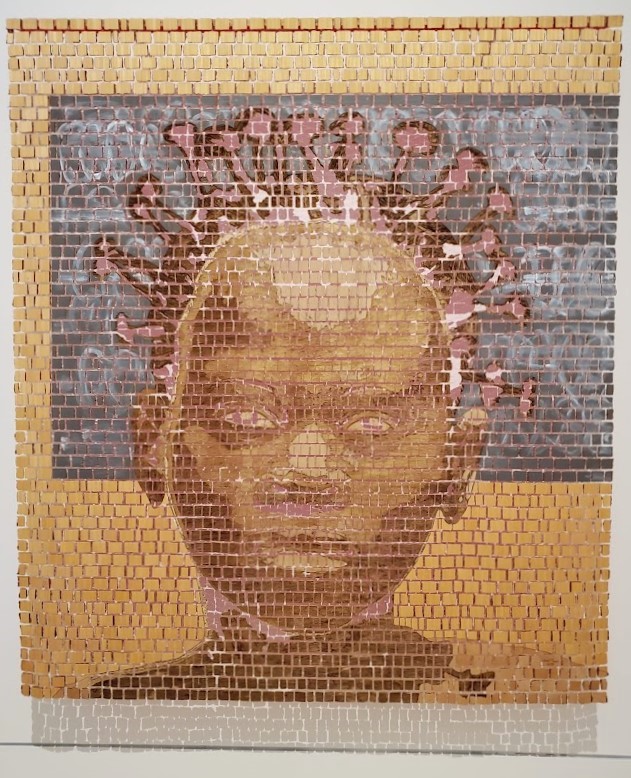

And we met a few new (to us) artists, too. Karel Appel’s found object and wood Roman Soldier sculpture drew a long look, but it was Aimé Mpane’s Maman Calcule (2013) that really intrigued us. So much so that the gallery guard asked us not to look so closely!

Karel Appel, Roman Soldier (2000)

Aimé Mpane, Maman Calcule (2013)

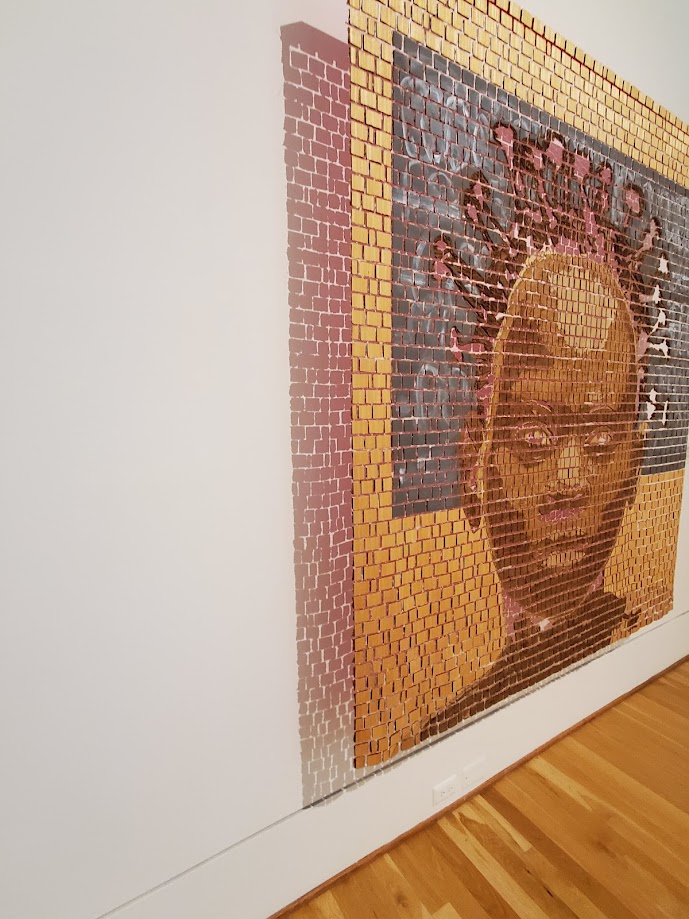

Maman Calcule, almost seven by six feet, is a penetrating portrait of a girl who stares, challenging, directly at the viewer. The intricate construction of acrylic and mixed media laid on shaved plywood was meticulously tied together with a network of monofilament. Backed with red pigment, a checkered red-tinted silhouette is cast on the wall directly behind the image, while angled shadow casts gradually lightening grey blocks. These simple optics, the physics of light, cause the small voids that surround the scalp to fill with color, causing the traditional Congolese hair style to become a non-traditional pink. The piece seems to vibrate with amplifying energy.

Angled view of Maman Calcule

Close-up of hair voids

Rear view of Maman Calcule

The Phillips Collection is a unique museum, with extraordinary art holdings, that has stayed true to the vision of its founder over the course of a century. The series of expansions connecting buildings along the block has created a few interior oddities, but the overall atmosphere maintains the sense of a small museum, without feeling cramped.

It’s not a small museum. It’s collection numbers on the multiple thousands … which leads to our one disappointment. Aside from the Jacob Lawrence Migration Series gallery, the display of artworks often struck us as rather sparse. So much empty wall space where more of the superb collection could be shown. We wanted more!

Hmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a little trip …

The Phillips Collection

1600 21st St NW, Washington, DC

202-387-2151

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the only search engine that makes it easy to discover more than 1600 art museums, historic houses & artist studios, and sculpture & botanical gardens across the US.

Just go to ArtGeek.art and enter the name of a city or state to see a complete catalog of museums in the area. All in one place: descriptions, locations and links.

Use ArtGeek to plan trips and to discover hidden gem museums wherever you are or wherever you go in the US. It’s free, it’s easy to use, and it’s fun!

© Arts Advantage Publishing, 2022