“This is the greatest exhibition of drawings we’ve ever organized,” says Hugo Chapman, Keeper of Prints and Drawings, at The British Museum.

When did drawing become something just kids do? Yes, I know — lots of artists do draw. But once upon a time — in fact, for centuries — all artists drew. Okay, there were exceptions — like Caravaggio; but he was an “I’ll do it my way” renegade, who just happened to have a super-human natural talent (and who, I believe, developed chiaroscuro so he didn’t have to learn to handle perspective. But that’s another story).

The dissing of drawing as an essential aspect of artistic practice is relatively recent, largely due to the late-19th century rejection of Academic rules and rigor by the young artists who forged Impressionism, craving creative freedom and spontaneity.

A proficiency in drawing was considered to be the foundation of Academic painting. Before being allowed to learn to paint with a brush, art students spent months copying prints after classical sculptures, then drawing from plaster casts of classical sculptures, and finally drawing from life. This was deemed to be the only way to fully understand the principles of contour, light, and shade. The quality of a student’s drawings was the basis for advancement to each successive stage of training.

The impetus behind the Lines of Thought exhibition was to foster a renewed belief in the value of copying and drawing to art education, art practice, and art appreciation. If any presentation of drawings can accomplish that objective, this one can.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Untitled (House and Landscape), 1916. Graphite on paper, 5 x 3 3/8 in. Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum [2006.05.030]

Although it’s pervasiveness waned, drawing as an artistic training and processing tool didn’t completely disappear in the 20th century. For example, in 1912, when she was studying at University of Virginia, Arthur Wesley Dow impressed upon a young Georgia O’Keeffe the importance of drawing, requiring her to draw increasingly simplified compositions. Drawing remained a crucial part of her artistic practice throughout her life. The 700 drawings in the collection of the Georgia O’Keefe Foundation eloquently attest to her 50 years of disciplined exploration and refinement of ideas through drawing.

Many of O’Keefe’s drawings are currently on display, paired with the finished paintings, at her namesake museum in Santa Fe, in a celebratory collaboration with two or three other local venues. Dubbed Art of the Draw, the focus of this summer program is to highlight drawing as the fundamental starting-point for creation: in art, engineering, design and architecture.

The capstone of this collaboration is at the nearby New Mexico Museum of Art, which is hosting an extraordinary, once-in-a-lifetime exhibition from the British Museum, Lines of Thought: Drawings from Michelangelo to Now.

By “extraordinary,” I mean: Hugo Chapman, Keeper of Prints and Drawings for the British Museum, calls it “the greatest exhibition of drawings we’ve ever organized.”

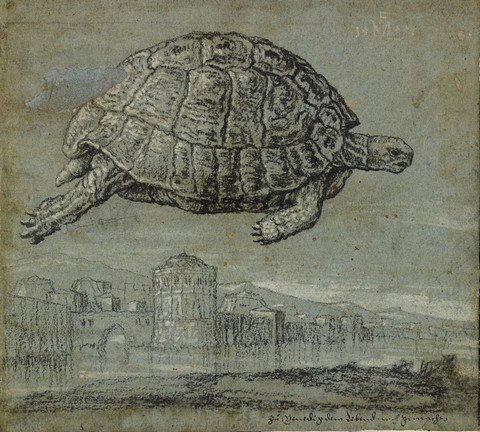

A Clump of Trees in a Fenced Enclosure, c.1645, black chalk. Image ©The Trustees of the British Museum

By “extraordinary,” I mean: this exhibition is a veritable Who’s Who in art history. The show presents 70 drawings by artists including Dürer, Michelangelo, Da Vinci, Raphael, Rembrandt, Rubens, Watteau, Claude Lorrain — to name but a few of the golden oldies — through Cézanne, Matisse, Seurat, Piet Mondrian, Picasso, Henry Moore — to bright lights like Bridget Riley, Michael Landy, and Julie Mehretu.

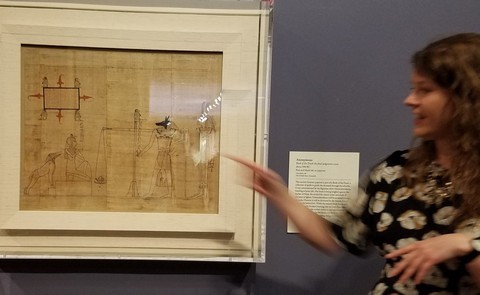

The oldest piece in the show is an Egyptian papyrus made circa 940 BC depicting a final judgement scene from the Book of the Dead. A close look reveals red draft lines created in planning out the composition, and exposes numerous reworkings made by the artist’s hand, 3000 years ago.

In much the same way as drawing served Georgia O’Keefe, to Op artist Bridget Riley “It is [the] effort to ‘clarify’ that makes drawing particularly useful, and it is this way that I assimilate experience and find new ground.” Henri Matisse said that he went to the Louvre to copy the work of others “to understand myself.”

The exhibition is organized thematically, structured around the premise of drawing as a “thinking medium,” underscoring its role in the creative thought process. Isabel Seligman, exhibition curator from the Department of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, explains that the works are “grouped not chronologically, but according to the different types of thought processes that drawing both records and demands. Initial thoughts, brainstorming, inquiry, association, and development are all visible in drawings by artists working centuries apart,” she says, “and bringing their work together demonstrates what can be learned from looking at masters of the past in the context of those working today.”

I dislike being told that I “must” do something, so I generally try to avoid saying “This is a must-see exhibition.” But …. this beautifully-curated collection of drawings really IS a must-see exhibition, whatever your relationship with art. Now’s the time to start planning a trip.

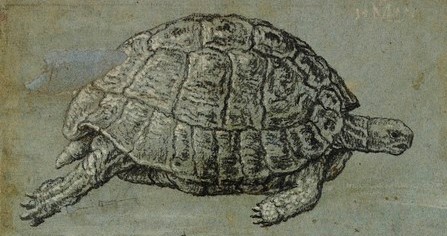

charcoal, heightened with white on blue paper

Image ©The Trustees of the British Museum

Lines of Thought: Drawings from Michelangelo to Now is on at the New Mexico Museum of Art, through September 17, 2017.

The only other showing in America will be on the east coast, at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum of Art, October 6, 2017 — January 7, 2018.

Then the drawings will return to the British Museum to be packed up in boxes and placed back in storage. According to Ms. Seligman, the works featured in this show are only allowed out once a decade because of their sensitivity to light. This may indeed be a once-in-a-lifetime exhibition.

As I said, “Extraordinary.”

Whether you visit the exhibition or not, the companion publication is illustrated by a selection of 120 highlights from the British Museum’s outstanding Prints and Drawings Collection. The text considers the types of thinking that produced these drawings ―brainstorming, inquiry, experiment, association, development and decision― giving us fresh insight into the creative impulse of some of the world’s greatest artists. The book is available here.

By ArtGeek.art on May 28, 2017.

Exported from Medium on January 12, 2019.