Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss began acquiring Byzantine art in the early 1920s. Within a single decade — as a result of their pioneering interest, their refined taste, and the connoisseurship of their advisers – the importance of their collection was already such that they were invited to lend numerous objects to the first major international special exhibition of Byzantine art, which took place in Paris in 1931.

Sharing a taste in both Byzantine and Pre-Columbian art, the Blisses developed two unique collections, acquiring artwork “in a new pattern, where quality and not number shall determine the choice.” Although far-reaching in scope and wide-ranging in stylistic expression, the collections are unified by the objects’ rare beauty and refined craftsmanship.

The Blisses continued to build their art holdings throughout their lives. As their knowledge deepened, they moved beyond the private collectors’ passion to the insightful establishment of specialized collections that appeal equally to amateurs and research scholars alike.

Today the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection is a Harvard University research institute. It attracts researchers to study its books, objects, images, and documents, and it attracts art geeks like us to explore the museum galleries.

These world-class collections of Byzantine and Pre-Columbian art and an historic Beatrix Farrand-designed garden are hidden behind high brick walls in residential Georgetown (Washington, DC). We recently had the good fortune to visit Dumbarton Oaks. In this article, we focus on our experience of the Byzantine arts collection. We write separately about gardens here and the Pre-Columbian art here.

Today the Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Collection comprises more than twelve hundred objects from the 4th-15th centuries, representing the imperial, ecclesiastical, and secular realms. Among the most important objects are vessels in precious metals, treasures used in the celebration of the Eucharist. Other outstanding objects are late Roman and Byzantine jewelry, cloisonné enamels, glass and glyptics, ivory icons, and illuminated manuscripts. A purposefully curated selection of these objects is on display in the small Byzantine Gallery and the elegant Courtyard Gallery.

The exhibit covers five main overlapping themes: the spiritual realm, personal adornment, imperial imagery, icons, and funerary practice. Throughout, an emphasis on precious materials—silver, ivory, gold, and gemstones—underscores the luxurious nature of Byzantine art. Beautifully decorated functional objects also are shown to have been important in Byzantine life.

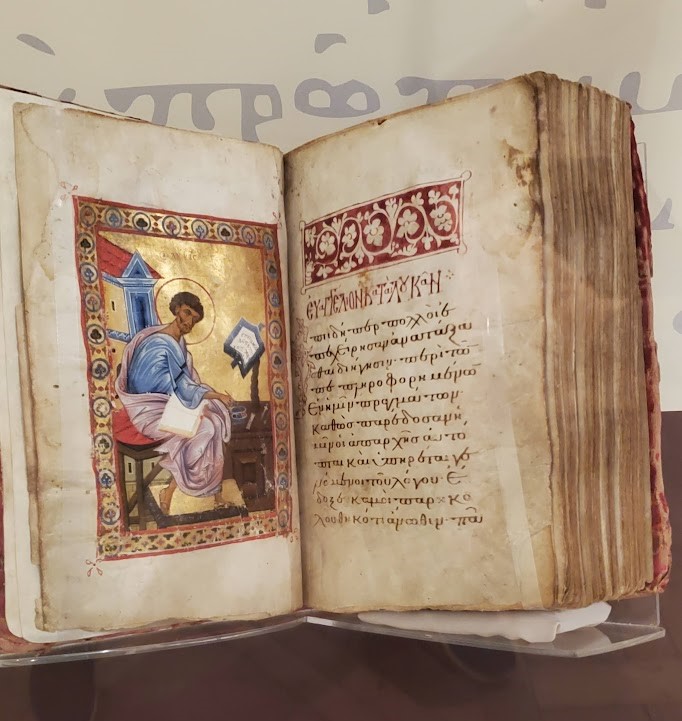

We are always drawn to illuminated manuscripts, charmed by the idea that their creation was a protracted, exacting, and reverential labor of faith, each book a unique jewel to be used as a tool of sacred ritual. A stunning example on display was a Gospels of Luke and John which contains two full-page illuminated author-portraits of Saints Luke and John. It was written on parchment — probably in Constantinople in the second half of the thirteenth century — “by one scribe in an archaizing Greek liturgical miniscule script.”

Tempera, gold leaf and ink on parchment

The manuscript is open to the portrait of St. Luke. Adjacent text tells us, “The book is open to the first words of his gospel. The real aim of this author portrait is not to present an historical act of writing, but rather to illustrate the moment of divine inspiration.” And the details of the image are described: “Luke sits working with his tools in front of him, including a dual ink well with red and black ink (red for emphasis), scissors for trimming his reed pen, and a bookstand holding finished pages.” Of course, these are the same tools the monk illuminating this manuscript would have had on his own work-table.

Another shining example of the art of illumination was a manuscript leaf picturing St. John and Prochoros. Although the Gospel writers are usually shown inside a study, at a writing desk, on this leaf the artist instead depicts John in a mountainous landscape, dictating his Gospel to his secretary Prochoros. We’re told that this suggests the island of Patmos in the Eastern Aegean, where, according to tradition, John was exiled by the Emperor Domitian, a fervent persecutor of the Christians.

Initially we were perplexed by the strange construct on the left side of the image until we found this interpretation: A furry animal with short ears, holding a codex, emerges from the top of the mountain. Though it may appear more like a bear than a lion, it almost certainly is a lion. (How does one paint a lion if one has never actually seen a lion?) The prophetic book of Ezechiel begins with a vision of four beasts; a man, a lion, a calf, and an eagle (Ez. 1:1-21), which were linked early on to the four Evangelists. John is traditionally paired with the lion. The codex held in the lion’s paws suggests that this is a moment Godly inspiration, inducing John’s dictaton of divine words to Prochoros.

Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss acquired their first manuscript for the museum in 1939. Over the years, the holdings have come to include four Greek manuscripts, one Georgian manuscript, three illuminated leaves from Greek manuscripts, one illustrated leaf from an Armenian manuscript, and four papyrus fragments with Greek writing.

Another object that particularly appealed to us was the ivory and bone Rosette Casket with Deesis, Apostles and Saints from the second half of the 10th century. Not only is it an example of refined craftsmanship, but it is also extremely rare. Boxes clad in ivory and bone were seldom decorated with Christian imagery: of the approximately 65 extant ivory and bone boxes known from Byzantium, only four have Christian figures.

Another intriguing piece was the top section from a niche in a tomb in late Roman Egypt, deeply carved in a soft limestone. The pagan god, Dionysos, is shown returning to his temple, both his home and place of worship. The scrolls of leaves, lotus buds and a vine with ripening grapes that surround him refer to the autumnal season, the time of year that anticipates the cycle of death and future rebirth. These symbols which were widespread in the ancient world, were naturally associated with the idea of resurrection, making this image an appropriate theme for a tomb.

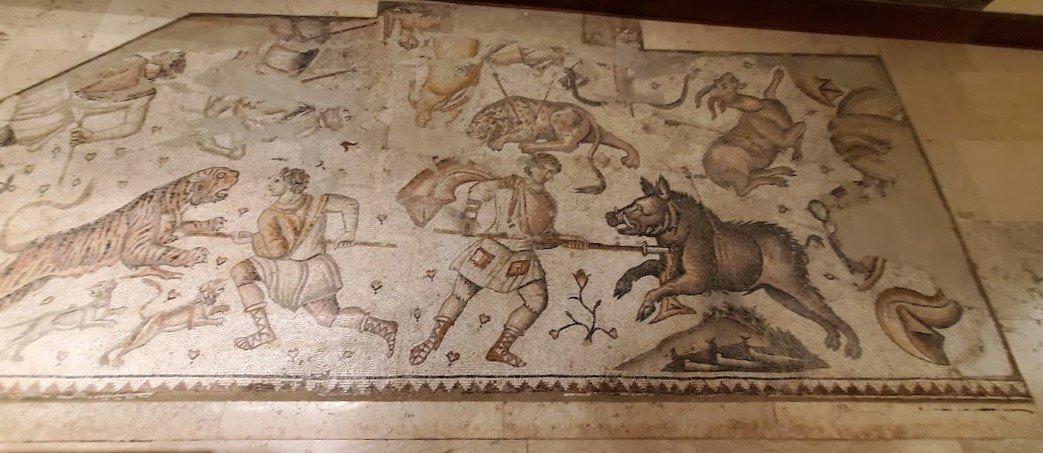

A small but significant collection of art from the ancient Mediterranean was acquired to complete Dumbarton Oaks’ documentation of the history of artistic styles, techniques, and iconographies. Viewed alongside Byzantine art, these objects offer an opportunity to consider the continuities and changes in artistic production from the classical to medieval periods.

To this end, we encountered a fragment of a delicate relief carving as well as some wonderful figurative mosaics installed throughout the museum.

Lasting Impressions: People, Power, Piety (on through Dec 4, 2022)

A real surprise for us was our engagement with the special exhibition of seals mounted in the courtyard, Lasting Impressions: People, Power, Piety. For more than a millennium Byzantines from every walk of life used lead seals to guard and authenticate documents and objects, and to identify themselves and present their credentials to the world.

These tiny objects at first seemed to us too esoteric to be interesting, with the obtuse assumption that “if you’ve seen one you’ve seen them all.” That proved not to be the case.

The exhibition promised to reveal the narratives that are told by the intricate impressions on Byzantine lead seals, and — due to the excellent supporting text — it delivered. As it turns out, each lead seal is a small witness to an individual Byzantine and how he chose to present himself (and occasionally, herself) in society.

The designs and inscriptions pressed into seals were personalized by their owners to present information about their status, position, piety, and family. By tracking the seals of individuals, researchers have pieced together their lives, relationships and family histories, learning a great deal about the times in which they lived. The images and inscriptions on seals illuminate developments in popular piety, the evolution of concepts of status in the empire, and the inner workings of the Byzantine state. This is art history!

Dumbarton Oaks is home to the most important collection of Byzantine lead seals in the world, numbering some 17,000 specimens, providing a rich source of information about the Byzantines and their empire. Ranging from the fourth to fifteenth centuries and covering a wide swath of Byzantine society, seals provide a unique lens through which to view social, institutional, religious, and artistic developments in the empire. Now we understand why someone would dedicate him/herself to studying Byzantine seals!

Not one of DC’s better-known museums, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection is a proverbial hidden gem. The museum is in a beautiful, walkable part of town, and it provides an exceptional art history experience. While there is a fee to enter the garden, the museum itself is free — and it would be well worth it a twice the price! Highly recommended.

Hmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a little trip …

Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

1703 32nd Street, NW, Georgetown, Washington DC

202-339-6400

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the only search engine that makes it easy to discover more than 1600 art museums, historic houses & artist studios, and sculpture & botanical gardens across the US.

Just go to ArtGeek.art and enter the name of a city or state to see a complete catalog of museums in the area. All in one place: descriptions, locations and links.

Use ArtGeek to plan trips and to discover hidden gem museums wherever you are or wherever you go in the US. It’s free, it’s easy to use, and it’s fun!

© Arts Advantage Publishing, 2022