Asheville is an art town, boasting two separate studio & gallery districts, numerous art and craft-related museums and historic houses … and the recently expanded Asheville Art Museum. The Museum’s collection of American art of the 20th and 21st centuries presents the narrative of art and culture in western North Carolina and Southern Appalachia, within the broader context of American aesthetic development.

This article considers the five special temporary exhibitions which were on view when we visited in early August, 2022. Read our separate article about the Asheville Art Museum and the Museum’s collection.

American Perspectives: Stories from the American Folk Art Museum Collection, on view through September 5, 2022.

Installation view

Installation view

American Perspectives is a thoroughly engaging, comprehensive special exhibition organized by the American Folk Art Museum in New York. By comprehensive, I mean everything I would expect to see in a presentation of works of folk and self-taught art from the 1700s to the present, including a painting by Grandma Moses, one of Edward Hicks’ 62 variations on the theme of Peaceable Kingdom, and an item of so-called “tramp art”. Given that these objects were drawn from the American Folk Art Museum Collection, they are superb examples of their type.

Tramp art, by the way, was the name given to objects made from wooden boxes and crates between the 1880s and 1940s. The Revenue Act of 1865 mandated the use of wooden boxes to pack cigars and tobacco, but did not permit the reuse of these boxes for that purpose. This made raw material freely available to those with the inclination and imagination to use it, even those in straitened circumstances. The clock shown here was given by Joseph Yoges to his landlord in lieu of rent money.

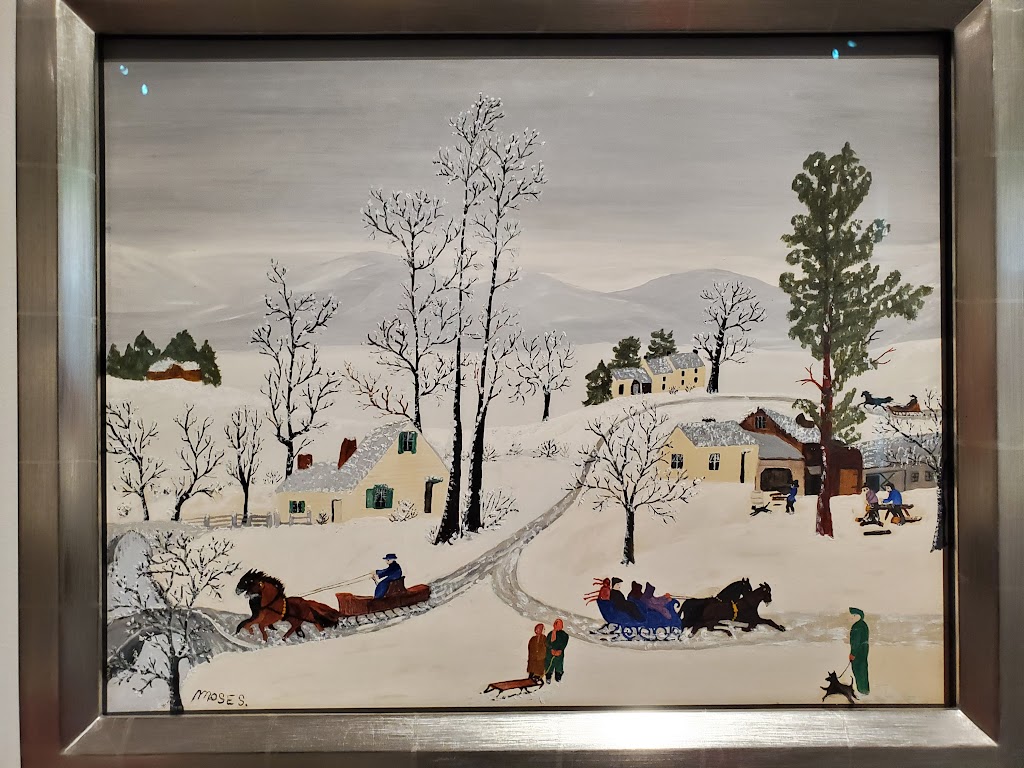

Dividing of the Ways, Grandma Moses, 1947

The Peaceable Kingdom, Edward Hicks, c.1830

Tramp Art Clock, Joseph Yoges, 1930s

The tradition of American folk and self-taught art captures the diverse stories of the American experience in evocative visual narratives. Curation of this exhibition builds on four themes: Founders, Travelers, Philosophers, and Seekers, giving palpable meaning to these firsthand testimonies about the unfolding narrative of our nation.

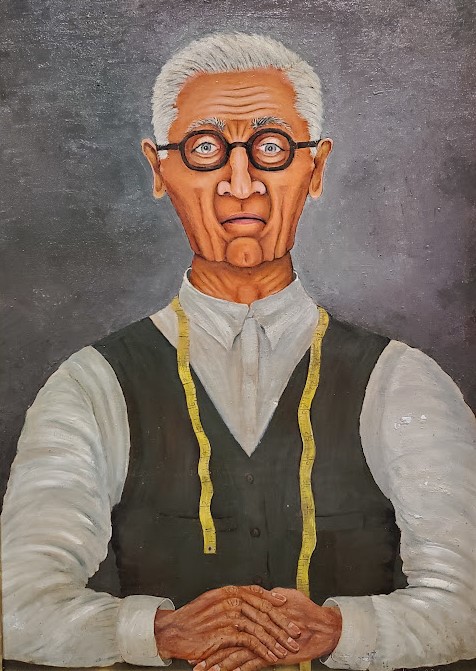

I was struck by the stories told by numerous works of portraiture, both recent and of the past. Two of them were particularly engaging.

In 1965, Joseph P. Aulisio (1910-1974) painted a posthumous portrait of his former employee, Frank Peters, who worked as a tailor at Aulisio’s business, Lease Dry Cleaning. Aulisio, a first-generation Italian-American had worked as a forest ranger before settling down and opening his business, while Peters, a Polish immigrant, was a coal miner before taking up tailoring in Aulisio’s store. The adjacent signage points out that “folds in Peters’ face appear both soft and hard, like molded plastic; each gnarled knuckle and the vein in his hands is delineated.” The tape measure draped around his neck speaks to his vocation.

Joseph P. Aulisio, Frank Peters, 1965

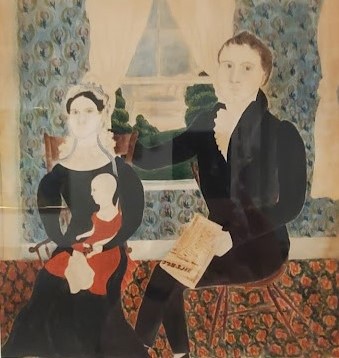

Deborah Goldsmith, Mr. and Mrs. Lyman Day and their daughter Cornelia, c.1824

Almost 150 years before Frank Peters was immortalized in paint, Mr. and Mrs. Lyman Day and their daughter Cornelia were captured in watercolor and pencil on paper by Deborah Goldsmith. Goldsmith was one of only a very few women who worked as a professional itinerant artist in early 19th-century America. Between 1824 and her marriage in 1832, she moved from town to town in western New York state, painting commissioned portraits. The family is shown dressed in their “Sunday best,” and Mr. Day holds a newspaper, perhaps to suggest a certain worldliness despite living in small-town America. The Days were probably among her earliest sitters, and she would have been 15 or 16 years old at the time — which perhaps accounts for the limited detail in facial features.

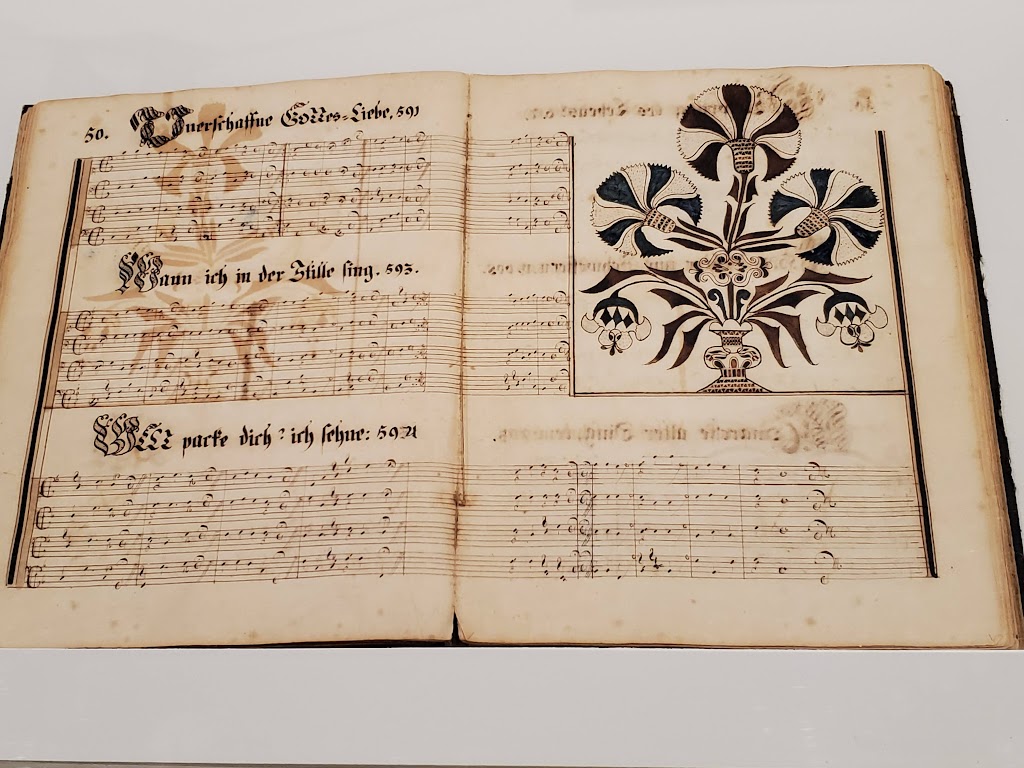

Some favorite objects in this exhibit include the Ephrata Cloister Tunebook, and the Outer Row Jumper Horse carousel figure.

Ephrata Cloister Tunebook, c 1745, by an unidentified artist

Outer Row Jumper Horse, circa 1918, Charles Carmel

The Ephrata Cloister Tunebook (circa 1745, artists unknown) is from the celibate monastery for men and women established in Pennsylvania in 1720. The cloister is celebrated for its original texts for hymns and illuminated books.

Outer Row Jumper Horse (circa 1918, Charles Carmel). Carmel was a Jewish woodcarver who emigrated to Brooklyn NY, home of the most exciting amusement park of the day, Coney Island. Sadly, much of his work was destroyed in a Coney Island fire, but a few of his works survived, including this elaborately outfitted horse embellished with glass “jewels”.

Two other favorites were Two Dreamers and Tiger …

Two Dreamers, 1966, Harry Lieberman

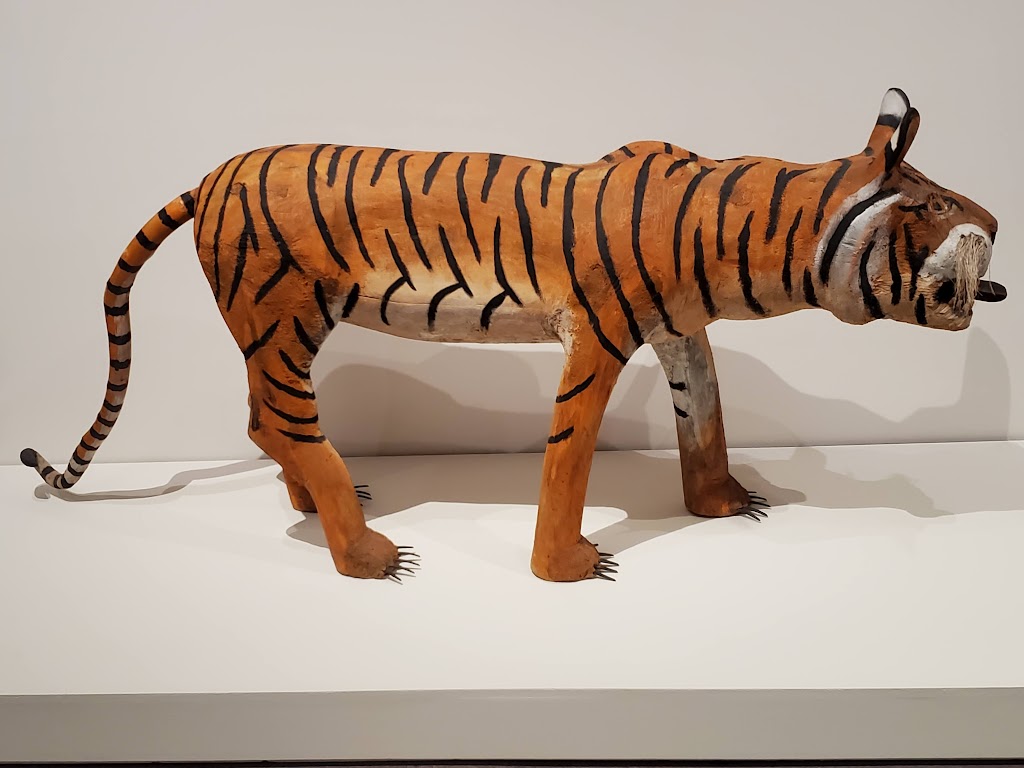

Tiger, 1977, Felipe Benito Archuleta

In 1966, when he was 86 years old, Harry Lieberman painted Two Dreamers, reflecting on the secular and religious paths taken by immigrant Jews. While he lived a largely secular life, working in textile trading and operating a candy store, this painting suggests a certain ambivalence as he neared the end of his life (he lived to 103!).

Felipe Benito Archuleta’s 1977 Tiger, carved from cottonwood, derives from the traditional New Mexican wooden “santo” — a type of simple religious figure carved by a “santero”. Archuleta began carving animal figures after he retired from a career in the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America.

The open areas at the top of the stairs on Levels 2 and 3 are referred to as Core Gallery spaces. When we visited, two 20th-century decorative art exhibits were on view: Studio glass on the 3rd level, and Arts and Crafts silver on the 2nd level.

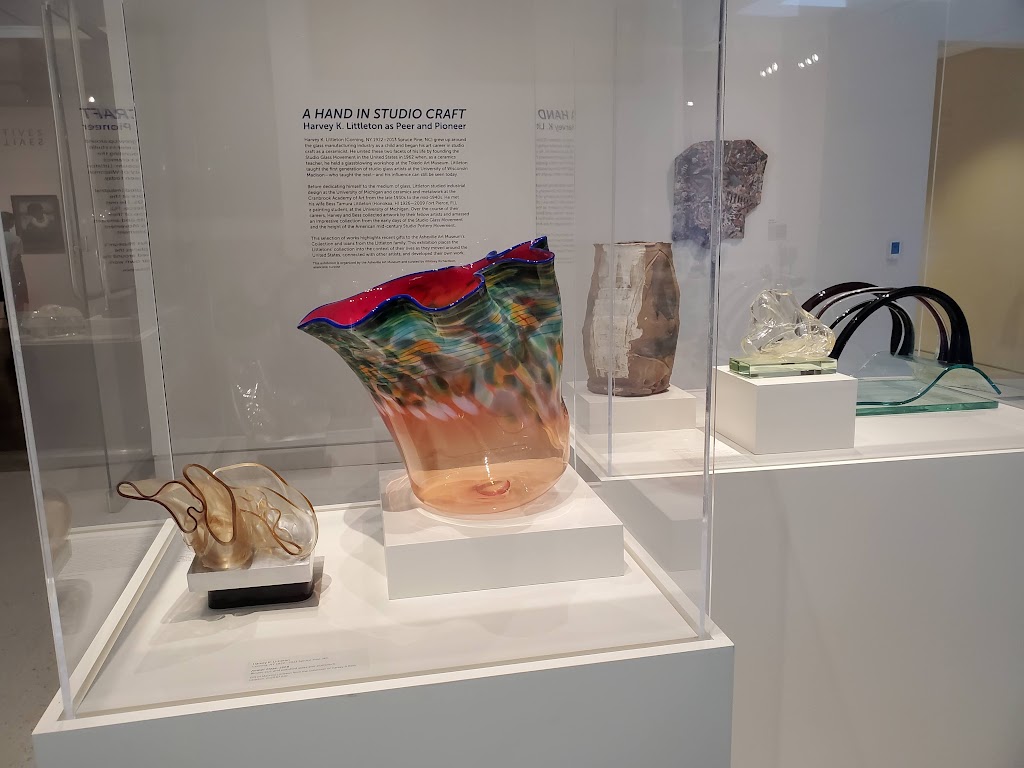

A Hand in Studio Craft, on view through Sept 19, 2022

A Hand in Studio Craft Installation view

Harvey K. Littleton, Amber Maze, 1968

The pieces on display are from the Museum collection as well as the collection of Harvey K. Littleton, the man who founded the Studio Glass Movement in the United States. The emphasis of the movement was on the artist as designer and maker, focused on making one-of-a-kind objects.

As a teacher in 1962, Littleton instituted a glass art program at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, the first of its kind in the US.

Littleton had studied industrial design, ceramics, and metalwork in the late 1930s and early 1940s, all of which informed his work in glass. He taught the next generation of glass artists—who taught the next—and his influence can still be seen today. Among his early students were Dale Chihuly and Marvin Lipofsky, artists who have played seminal roles in raising the awareness of studio glass around the world.

Over the course of their life together, Harvey and his wife, Bess, collected artwork by fellow artists and amassed an impressive collection from the early days of the Studio Glass Movement. This exhibition presents their collection in the context of their lives, as they moved around the United States, connected with other artists, and developed their own work.

Useful and Beautiful, on view through October 17, 2022

Useful and Beautiful installation

William Waldo Dodge Jr., Teapot, 1928

“Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.” So said William Morris, a founding member of the English Arts and Crafts Movement.

The Arts and Crafts design movement began as a reaction against the perceived decline in design standards associated with machinery production, and against the conditions in the factories in which they were produced. Design, it was felt, had become excessively ornate, artificial, and ignorant of the qualities of the materials used.

As a trained architect and a newly skilled silversmith, Dodge moved to Asheville in 1924 and opened a silversmithing business in a true Arts and Crafts tradition.

The aesthetics of his work were dictated by the Arts and Crafts philosophy: an artist’s handmade creation should reflect hard work and skill, and the resulting artwork should highlight the material from which it was made. Dodge’s silver often displayed his hammer marks and inventive techniques, revealing the beauty of these useful household goods.

The silver works in this exhibition are drawn from the Museum’s collection of silver tableware handwrought by William Waldo Dodge. Every piece is beautiful in simplicity and elegant in functionality.

Border Cantos: Richard Misrach | Guillermo Galindo, on view through Oct 24, 2022

Much has been written about this exhibition, which has been touring America’s museums since 2016. It is at once sobering and amusing, political and spiritual, depressing and uplifting.

In this exhibition, photographer Richard Misrach and composer Guillermo Galindo give presence to the thousands of undocumented immigrants who cross into the US each year, and encourage a humanitarian perspective on the plight of all immigrants. They bring the border down to human scale, and place the divisive issue in the context of individual human lives. Border Cantos offers a provocative response to the polarizing discussions around undocumented immigration that have dominated local, national and global politics throughout history.

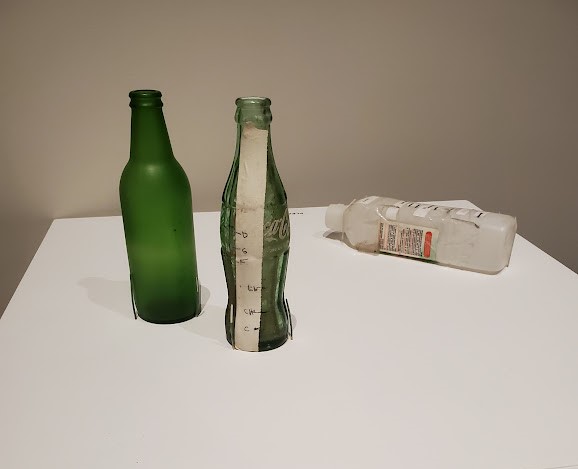

Misrach’s outsized landscape photographs are stark and expressive. The minimalism in his pictures speaks volumes. Their voices are accompanied by an audio installation of Galindo’s non-melodic, somewhat disturbing, original compositions. The sound we hear throughout the exhibition was scored for his “assemblage” instruments — found-object instruments created from refugee detritus — which are on display.

Guillermo Galindo, Cokeflute, Pediaflute, Bottleflute, 2012-14.

Guillermo Galindo, Teclata, 2014

Together the artists bear witness to the human consequences of what is in fact a global problem. Through their art, the artists have brought the intractable border issue into an intellectual and emotional perspective, spotlighting it in the context of individual human lives.

Draped and Veiled, through Oct 10,2022

Working with a large-format Polaroid 20″×24″ camera—weighing 200 pounds and the size of a refrigerator—Joyce Tenneson has produced a poetic series of images featuring partially and fully nude figures that seem to float in a diaphanous layer of veiling. The large dye-transfer prints balance subtlety with boldness, pairing softness with an undeniable presence.

The equipment Tenneson uses creates quite a different relationship between photographer, subject and camera than does the more common method of photography. The unique quality of these images is a result of the 20″x24″ film plates and the rapid development of the Polaroid film. Only six of these enormous cameras were made between 1976 and 1978, and five of them are still in use. Artists rent time and set up their shots in specialized photography studios in order to use one of these cameras.

The 12 large Polaroids in this exhibition are from Tenneson’s Transformations series, which she began in 1985 and continued through 2005. The images feature elements that feel vaguely mythological or symbolic — and certainly lyrical.

The Ashville Art Museum is welcoming, easy to navigate and provides a varied and informative art experience. While special exhibitions will change over time, if they are always of the quality that were on view when we visited, then — in addition to the permanent collection installation — this museum is definitely worth a visit. Recommended!

Hmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a little trip …

Asheville Art Museum

2 South Pack Square, Asheville, NC

828-253-3227

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the only search engine that makes it easy to discover more than 1600 art museums, historic houses & artist studios, and sculpture & botanical gardens across the US.

Just go to ArtGeek.art and enter the name of a city or state to see a complete catalog of museums in the area. All in one place: descriptions, locations and links.

Use ArtGeek to plan trips and to discover hidden gem museums wherever you are or wherever you go in the US. It’s free, it’s easy to use, and it’s fun!

© Arts Advantage Publishing, 2022