Good news for art and history geeks! The superb exhibition, Visions of the Hispanic World: Treasures from the Hispanic Society Museum & Library, originally scheduled to close at Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts at the end of May, has been extended to September 7, 2020.

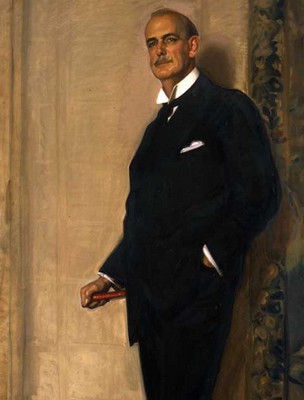

Scholar, patron of the arts, and man of means, Archer Milton Huntington (1870–1955) is today the little-known name behind a legacy of three exceptional museums, including the Brookgreen Sculpture Garden in Murrells Inlet, SC and the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, VA — one of the largest maritime museums in the world.

by José María López Mezquita

But Huntington’s greatest passion was Spanish culture, and it was his extraordinary collection of Iberian and Spanish-Colonial art that became the foundation of the Hispanic Society of America in New York City.

The collections of the Hispanic Society reveal the history of Spain and its place in the world, from antiquity to modern times. Unrivaled outside Spain, the holdings of the “Spanish Museum” focus on all facets of art, literature, and culture in Spain, Portugal, Latin America, and the Philippines up to the early 20th century. The scope and quality of the collections is hard to believe, considering that they were largely amassed by a single inspired collector.

Archer Huntington was precocious. His love of Hispanic culture and language began in childhood, and by age 16 he was a serious student of art history and noted that his “collection now fills four trunks.” Ignoring contemporary public sentiment, in 1904 he founded the Hispanic Society of America, while many Americans still harbored animosity towards Spain. It was just six years after the Spanish American War, which had cost the United States $250 million and taken 3,000 American lives.

Undoubtedly, Huntington spared no expense in the design and construction of the original Hispanic Society building — but that was more than a century ago, and the Museum is now closed for extensive renovations. Rather than putting the entire collection into storage, a exemplary selection of objects has been organized into a travelling exhibition,Visions of the Hispanic World.

Following runs at the Prado in Madrid, and the Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, three US venues were selected to host the exhibition, starting with an almost 5-month stay at the Albuquerque Museum in New Mexico (through March 31, 2019), followed by the Cincinnati Art Museum (Oct 25, 2019 — Jan 19, 2020) and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (March 1 — May 25 Sept 7, 2020).

I spent some truly pleasurable hours, in two visits, at the exhibition in Albuquerque. Comprising more than 200 objects from the Iberian Peninsula and the Spanish colonies, spanning 4000 years, the Visions of the Hispanic World exhibition is — in a word — awesome.

Organized chronologically, the exhibition in Albuquerque was curated to highlight the various cultural influences that merged into an uniquely Iberian creative sensibility, as well as the geographic dispersion of hispanic thought and artistry.

The show begins with a survey of antiquity which includes 2nd millennium BCE pottery and beautiful examples of ornate Celtiberian metalwork, like the choker pictured here.

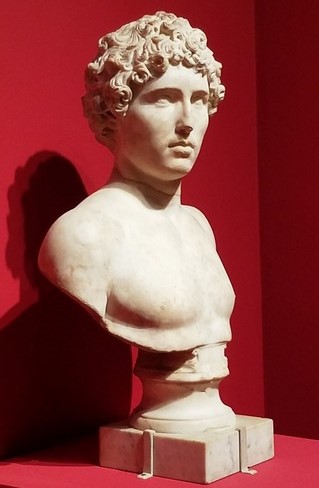

Subsequently, the Romans came to Spain in 206 BC, invading the Iberian Peninsula from the south. They defeated the Iberians and founded the town of Itálica, near today’s Seville.

As they were wont to do, they imposed the Roman way of life on their new colony. The peninsula remained under Roman occupation for seven centuries.

Exquisite works of art and craft were created during that time, and the exhibition provides a few fine examples of sculpture, mosaics, and metalwork.

I was particularly charmed by the large double-wick lamp with a mask in relief representing Pan. The artistic quality compares to the best work created in Herculaneum and Pompeii.

Pan, in Greek mythology — and his Roman equivalent, Faunus — is the god of the wild, and of shepherds and their flocks. He is often affiliated with masculine sexuality … due to a proclivity for pursuing nymphs through wooded glens. Since he is also associated with the god Dionysus, or Bacchus — who shared similar avocations — the mask of Pan could indicate that this lamp served as a ritual vessel for a Bacchanalian cult.

Between the 5th and 15th centuries diverse cultures inhabited the Iberian Peninsula, and the medieval collections reflect these various influences. Contrary to prevailing opinion among his contemporaries, Huntington considered Spain’s Islamic legacy to be as important as its Christian heritage. This informed scholarly view is substantiated by the medieval art objects in this exhibit.

tin-glazed earthenware with cobalt and luster

In addition to “pure” Islamic pieces crafted in the Muslim territories — Muslims in Granada were under self-rule until 1492 — there was a hybridizing receptivity to Islamic influence in the Christian Kingdoms where Muslims lived under Christian rule for generations.

Toledo, ca. 1400–1450

Indeed, Muslim potters dominated ceramic production in Castille through the 15th century.

An octagonal maiolica baptismal font made in Toledo, ca. 1400–1450, shows Islamic motifs embellishing a Christian religious object. In addition to the stylized interlaced banding, the font is decorated with an open right hand — the ancient symbol of the hand of Fatima –a protective talisman against the evil eye in the Islamic world, which was assimilated by the Jewish and Christian communities.

The design of Alhambra silks, also known as “striped Granada cloth,” recall the tile designs of the Alhambra of Granada. An exceptional example in this show is unique in having been preserved in one piece. Given its size, it would have been woven on a very wide loom and possibly served as a wall hanging or curtain. The decorative motifs are in nine parallel bands on a red and yellow background. In the cartouches that form the interlaced design, inscriptions in Nashk and Kufic characters read, “perpetual honor,” “prosperity and good fortune,” and “happiness”.

Moorish art, materials, and techniques engendered a style of elaborate decoration of inlaid bone, ivory, and precious woods. Known as Mudéjar, the style characterized luxury objects. The medieval Spanish term was taken from the Arabic word Mudajjan — meaning “tamed” — to refer to Moors who remained in Iberia, submitting to the rule of Christian kings.

One especially fine example of Mudéjar craftsmanship is a 16th-century walnut chest, encrusted with intricate ivory inlay. Other than a few dings and losses around the base, the inlaid detail looked to me to be virtually pristine.

Moving on chronologically, the exhibition reveals that the Spanish “Golden Age,” was much more than the paintings of Velazquez and Murillo, El Greco and Zurbaran, all of whom are represented here. Clearly, the artistic sensibilities of the era extended into many creative fields, including pottery, glassmaking, precious metalcraft and polychrome terracotta and wood.

glass with enamel and gilt

Perfect condition of works in this collection is not unusual. With a few exceptions, the quality of preservation of most of the objects in the show is stunning. A 16th-century Pilgrim Flask stopped me in my tracks. To my eye it appears flawless, despite being 450 year-old glass!

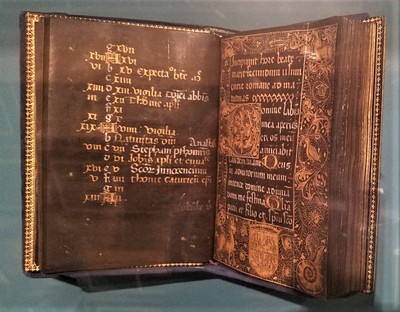

One display case is filled with an extraordinary line-up of illuminated manuscripts. In our era of abbreviated communication and electronic reading, the intricate, florid script and hand-painted embellishment of these beautiful objects underscores how privileged people were — for many centuries — to own a book.

The rarest of all is the 15th century Black Book of Hours, illuminated on black-stained vellum. This Book of Hours is thought to have been commissioned by or for María of Castile when her husband, Alfonso V of Aragon, died in 1458. The use of black parchment supports this theory, as does the fact that María’s Castillian coat-of-arms, which appears on the first leaf, is not shown united with that of Aragon. María died less than three months after her husband, which may explain why numerous miniatures were left unfinished.

The array of objects from the Americas includes maps and other parchments; oil-on-copper paintings and polychrome and gilded wood carvings of religious subjects; Asian-inspired lacquerware from Mexico; ceramics, including black micaceous small clay figures easily mistaken for metalwork, and finely-wrought objects in New World silver. It is in this part of the exhibition that we fully appreciate the global range of Iberian influence.

polychromed wood, glass, and metal

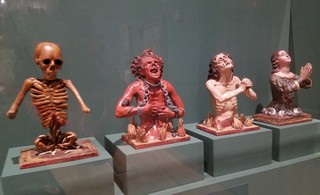

A most arresting item here is the The Four Fates of Man, a group of small polychrome sculptures from 18th century Quito, Ecuador. According to Catholic teaching at the time, death marked the separation of body and soul, and these four figures warned of the fate that awaits after death — the possibilities ranging from the frighteningly macabre to the sublime. Your skeleton will crawl with worms, and your soul will either endure the agonies of hell forever, wait in Purgatory hoping for purification, or be rewarded with the bliss of heaven. The message would not have been lost on an 18th-century believer!

The last segment of the show — Goya through the 1920s in Spain — is equivalent in scope to those that are grouped in Gallery 1. Given the physical separation of this final part of the exhibit (in the Albuquerque Museum), it is easy to overlook — but the paintings and works on paper here are not to be missed.

The knowns — Goya and Sorolla — are well represented, plus there’s a John Singer Sargent, The Spanish Dance (ca. 1880–1881).

Among the Goyas is his prized painting, Duchess of Alba — who had “not a single hair on her head that does not awaken desire,” according to one admirer. The Duchess greets visitors entering the gallery.

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828)

A gallery guide was overheard telling his group that left- and right-foot shoes had yet to be invented — and the duchess does appear to be calling our attention to her aching feet. But she’s actually pointing to words written in the sand, “Solo Goya” (Only Goya). She also wears rings inscribed “Alba” and “Goya” which has led to much speculation about their relationship. At the very least, we can assume that this painting had great personal significance for Goya since he kept it in his studio long after the duchess’s death.

Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (Valencia, 1863–Madrid, 1923),

Archer Huntington discovered the paintings of Joaquín Sorolla just months after the Hispanic Society opened, and he immediately initiated plans for an exhibition the following year. The exhibition was a sensation, attracting nearly 160,000 visitors in a single month, and Huntinton acquired some of Sorolla’s best works from that show, including After the Bath (1908) and Sea Idyl (1908).

Both those works are in this exhibition, along with a 1911 portrait of Louis Comfort Tiffany, himself captured at his easel in a riotously-colorful flower garden. The work demonstrates Sorolla’s approach: “Every effect is so transient, it must be rapidly painted. I could not paint at all if I had to paint slowly,” he once said.

And there are some lesser-known artists here worth meeting.

Hermenegildo Anglada Camarasa (Spain, 1871–1959),

Hermenegildo Anglada Camarasa, for example, was new to me. This picture reflects the avant-garde influence he absorbed in Paris in the 1890s. It is part of a large series he painted on Valencian themes, including falleras, or women associated with the fallas guilds at the famous Valencian March festival. The painting is carefully detailed, depicting all the elements of the traditional fallera costume: the full embroidered skirt, the silk lace shawl with gold embroidery, and the hair adornments and dangling earrings.

Santiago Rusiñol Prats (Barcelona, 1861–Aranjuez, 1931)

Another new-to-me artist was Santiago Rusiñol Prats, whose magnificent Calvario at Sagunto, Day’s End, exudes an appealing delicacy of color and clarity of form. Coming as it does at the end of this very substantial exhibition, I wished there were a bench in front of this large painting — to rest my tired feet and to quietly process the stimulation of the previous hours.

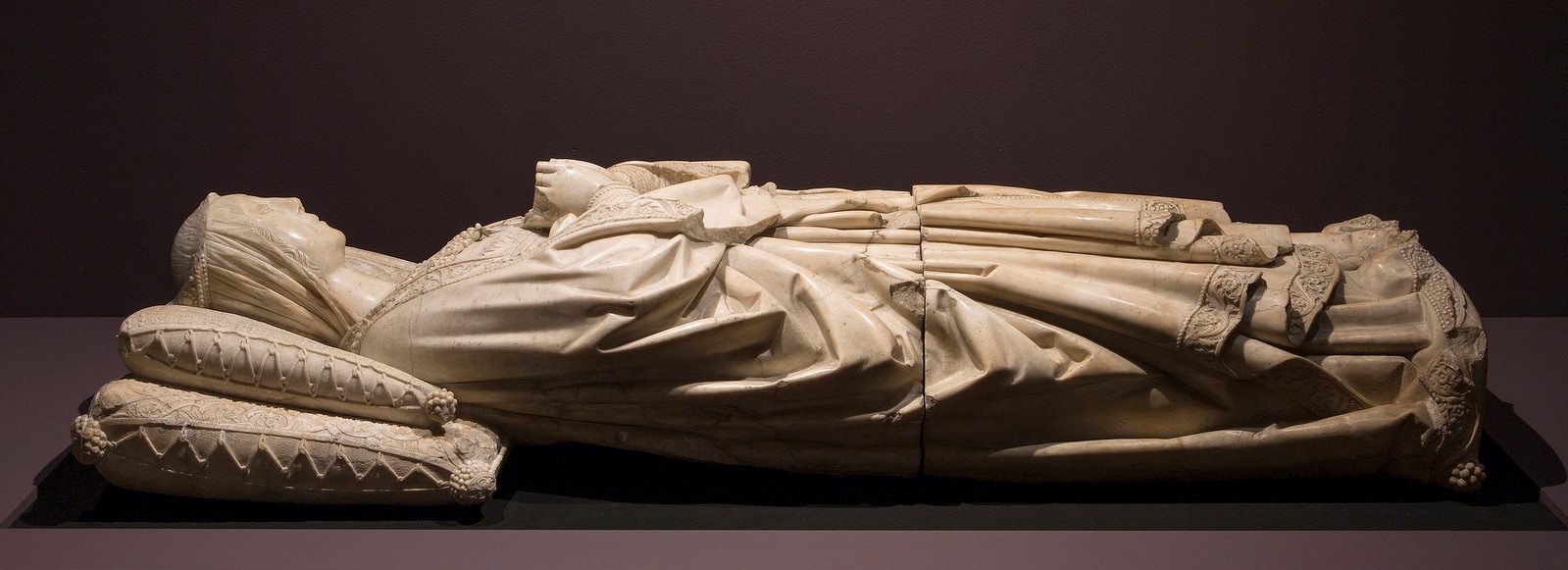

Workshop of Gil de Siloé, San Francisco de Cuéllar, Segovia

Featured banner image: El Costeño, The Young Man from the Coast (detail) Puebla, Mexico, c.1843, oil on canvas, by José Agustín Arrieta (Mexico, 1803–1874)

Visions of the Hispanic World is now at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston through Sept 7, 2020. (Before going, please check to be sure the MFA Houston has reopened.)

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

1001 Bissonnet, Houston, TX

713-639-7300

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the only search engine that makes it easy to discover more than 1300 art museums, historic houses & artist studios, and sculpture & botanical gardens across the US.

Just enter the name of a city or state to see a complete catalog of museums in the area. All in one place: descriptions, locations and links.

Use ArtGeek to plan trips, to discover hidden gem museums, and to find temporary art exhibitions that have special appeal to you — — wherever you are or wherever you go in the US. It’s free, it’s easy to use, and it’s fun!