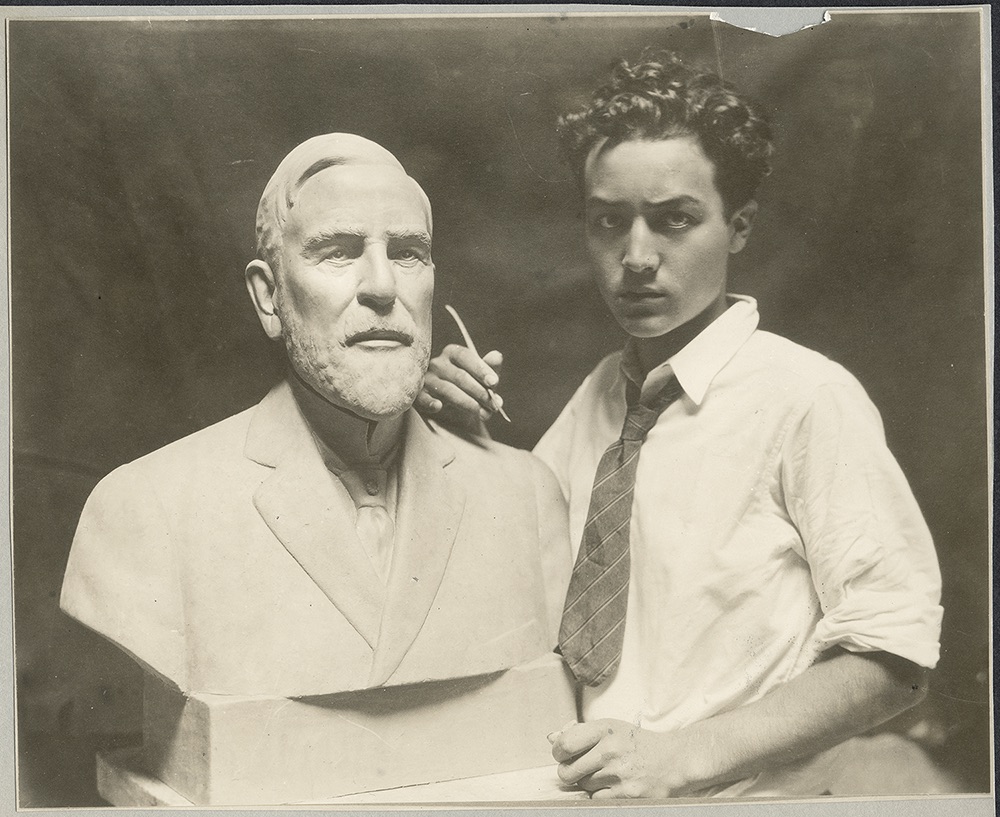

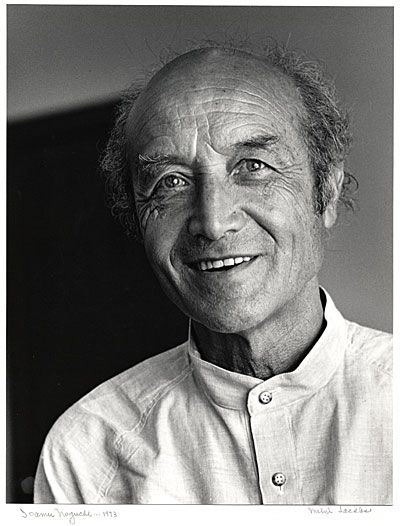

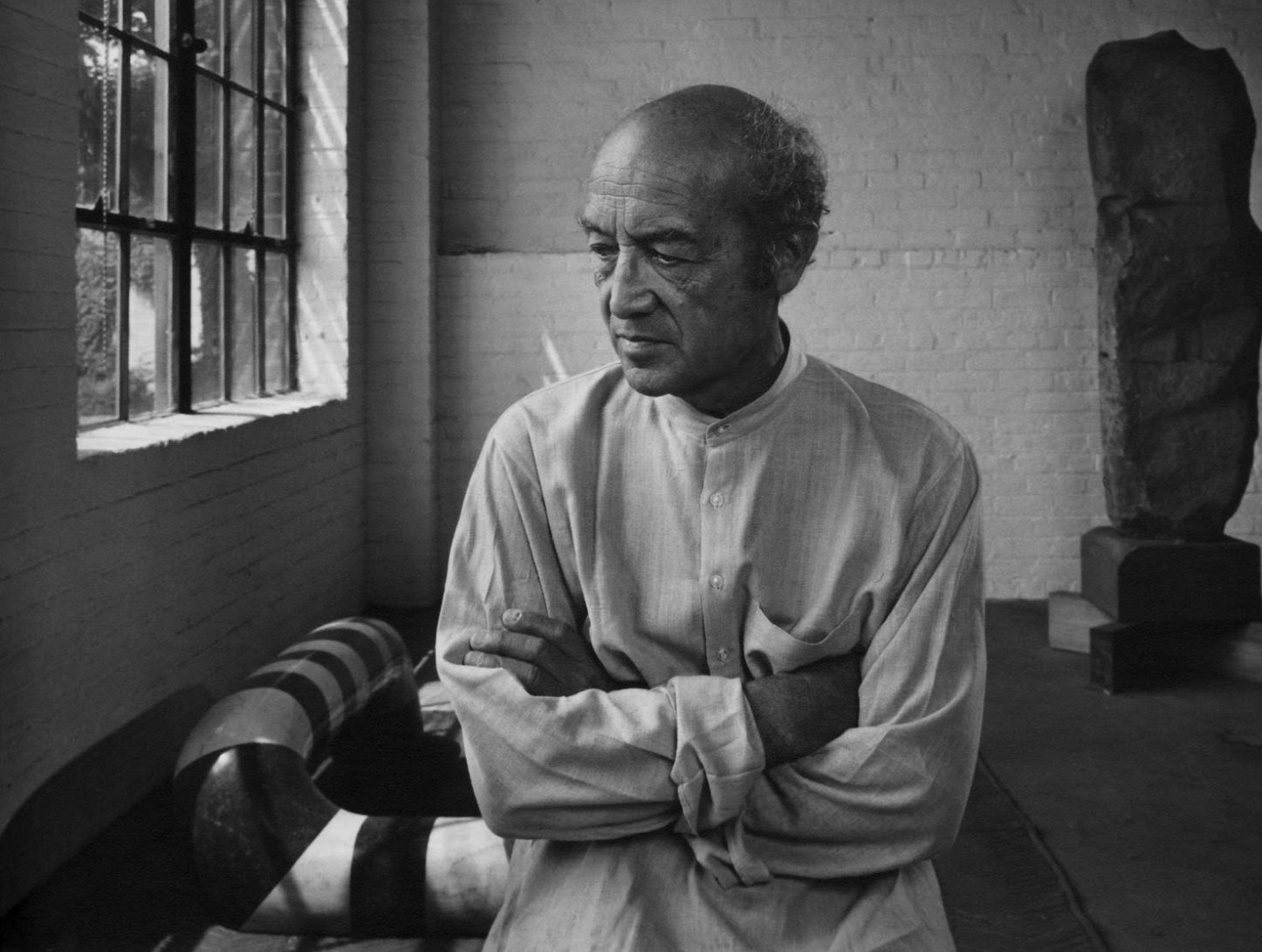

As a young man, the great American sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988) was almost diverted from the path of his true calling, his artistic aspirations squashed by really bad advice from a very big name in the field.

After completing high school, Noguchi apprenticed to Gutzon Borglum — the well-known American sculptor who is best known today for the four presidential portraits of Mt. Rushmore. The relationship didn’t last long; Borglum—old-school, opinionated and authoritarian—told Noguchi that he was not talented enough to become a sculptor. Discouraged, in 1923 Noguchi enrolled in the pre-med program at Columbia University.

Luckily—while most parents are more likely to encourage their son to become a doctor over becoming an artist—his mother urged him not to give up his dream. Four years later he was moving to Paris on a Guggenheim scholarship where he gained an apprenticeship to work with the abstract sculptor Constantin Brancusi. That relationship was a far better match and Brancusi became a major influence on Noguchi.

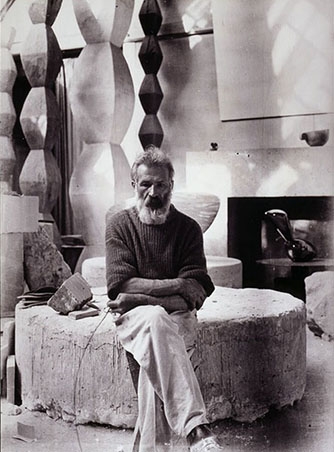

Brancusi installation, 2017

Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY

Constantin Brancusi

Autoportrait dans l’atelier, c.1933-34

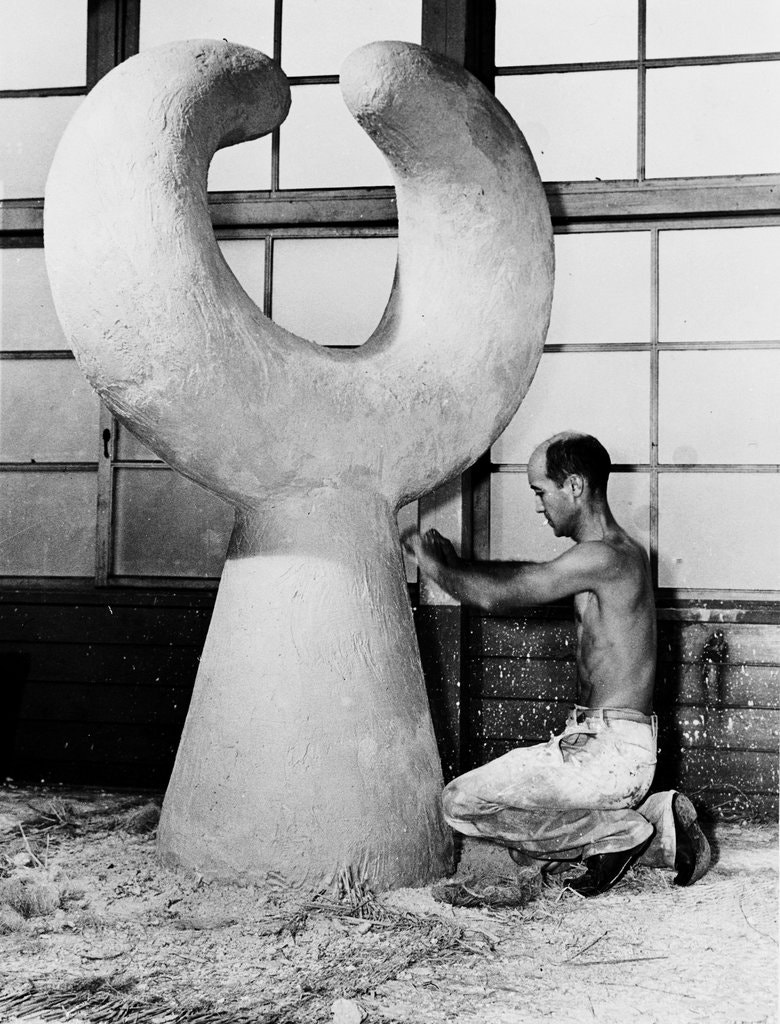

Two years (1927-29) in Brancusi’s “laboratory for distilling basic shapes” caused the young artist to turn away from academic sculpture toward modernism and abstraction. This he blended with a traditional Japanese sense of what he referred to as the “value of non-assertiveness.” His own language of simplified form began to emerge.

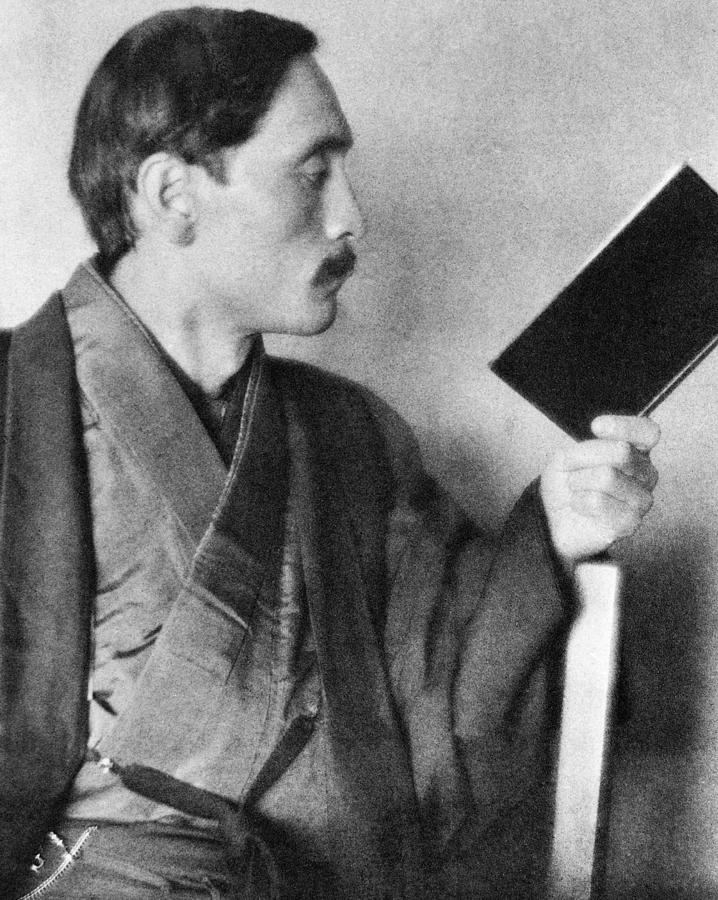

Noguchi’s Japanese father was a rising young literary figure in New York City. Yone Noguchi met Isamu’s American mother, Léonie Gilmour, when she answered his classified ad for freelance editorial work in 1901. They had a brief affair towards the end of his time in the US, and when he returned to Japan he left Léonie behind—six months pregnant.

Yone was prominent enough that when Isamu was born, a Los Angeles Herald headline read, “Yone Noguchi’s Babe Pride of Hospital. White Wife of Author Presents Husband With Son.” It would seem, however, that the “husband” was unimpressed with this gift. Although he contributed financially, Yone was quite absent as a father to Isamu.

Yone Noguchi (1875-1947)

Léonie Gilmour (1873-1933)

Léonie followed Yone to Japan, but life as a family did not come to pass. But it did mean that Isamu’s early upbringing was in Japan, and—before returning to the US to complete his secondary education—he apprenticed to a local carpentry artisan and cultivated an appreciation for the Japanese aesthetic.

As an adult he studied Japanese gardens, realizing that land, too, could be approached as a sculptural medium. Living in Japan, he said, made him “knowledgeable in the ways of nature” and instilled in him “respect for materials and how things are made.”

In 1988, the year he died, Noguchi recalled, “For one with a background like myself the question of identity is very uncertain. It is only in art that it was ever possible for me to find any identity at all.”

Thirty-five years ago Noguchi founded a museum to display what he considered to be representative examples of his life’s work. As the artist’s estate, the museum holds the world’s largest, most extensive collection of Isamu Noguchi’s sculptures, drawings, models, and designs.

In 1961 Noguchi had relocated to Queens from Manhattan, purchasing a single-story commercial building in a Long Island City neighborhood of skilled artisan shops and suppliers of stones and metals. He found it highly conducive to his studio practice. Unlike his Greenwich Village space, the remote location discouraged drop-in visitors and allowed him to maintain the monastic lifestyle he desired. Although he continued to travel extensively and had other studios in Italy and Japan, it was in this building that Noguchi created and stored most of his artworks for more than a decade.

He was so prolific that by 1974 he needed more space. Fortuitously, a building became available directly across the street from his current live-work space that would give him 10-times the square footage.

The property included a derelict enclosed yard and he saw its potential, envisioning a sculpture garden where he could display larger works. In transforming the courtyard, Noguchi brought in an abundance of trees and plants, which he selected for their texture and form.

Enclosed yard, c. 1931

Isamu Noguchi Garden, 2019

By 1980 he had decided to create a museum at this location, and the Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum officially opened to the public on May 11, 1985. It was the first museum in America to be established by a living artist for the display of his own work.

There is perhaps no more serene space in New York City than the Noguchi Museum and Garden, just across the East River, a few blocks north of the Queensboro Bridge. It is a place to appreciate — as the artist himself did — the Zen Buddhist concept of void (mu), which sees substance and nothingness as interdependent states of reality.

To visit the museum is to understand this idea that Noguchi once expressed: “If sculpture is the rock, it is also the space between rocks and between the rock and a man, and the communication and contemplation between.”

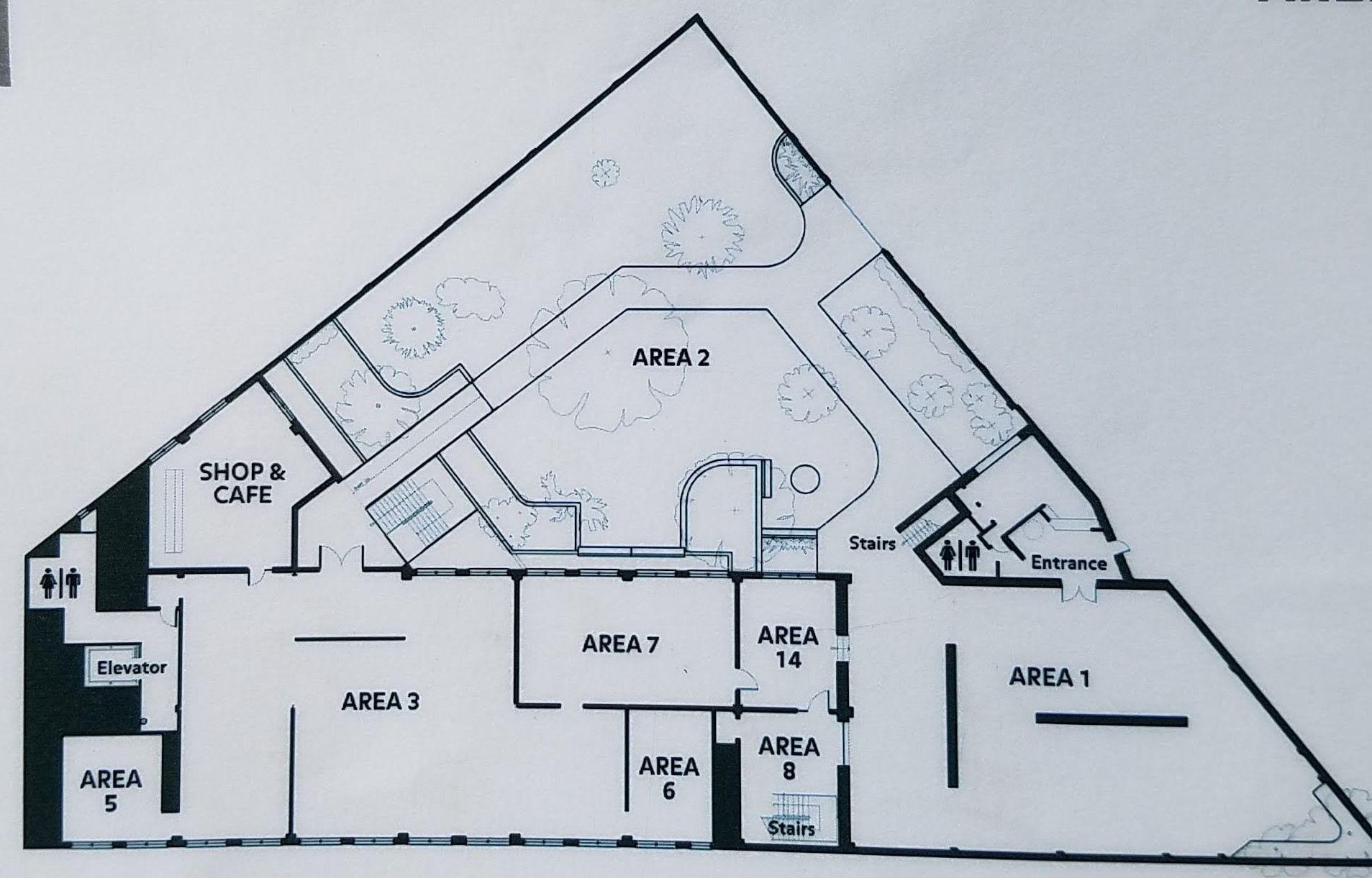

The two-story repurposed 1920s red brick industrial building contains approximately 27,000 square feet of exhibition space, including the arcadian sculpture garden. It also includes an “indoor/outdoor” attached pavilion (Area 1) that Noguchi added — after demolishing an old gas station that occupied this corner lot — to display his large basalt pieces. These are late career works, so our introduction to Noguchi’s work begins in reverse chronological order.

Mountain Breaking Theater (1984) basalt

Give and Take (1984), basalt

Some of these basalt pieces are monolithic statements of form. Others, besides being formally interesting, provide a repertoire of the textures that can be wrought from the fine-grained mineral-streaked matrix of this volcanic rock.

Much of the museum is washed with natural light that pours in through large windows overlooking the courtyard. The light, high ceilings, large rooms with white walls and gleaming wood floors create a tranquil environment that allows each piece to make its own stand-alone statement.

Right: Downward Pulling #2 (c.1972), red Alicante and black Marquinia marble

The light plays on the more polished works, drawing attention to the highly-refined finishes that Noguchi achieved.

Heart of Darkness (1974), obsidian

Sun at Noon (1969), French red marble, Spanish Alicante marble

Noguchi travelled throughout his life, absorbing aesthetic values wherever he went. In Mexico, it was large-scale pubic works; in China, ink-brush calligraphy; the appeal of marble in Italy; earthy ceramics in Japan, as well as garden and architectural design.

In a 1960 magazine profile of Noguchi, R. Buckminster Fuller wrote, “… Isamu has always been inherently at home—everywhere. He has to-and-froed in his great back and front yards whose eastward and westward extensions finally merged in world encirclement … it is safe to say that Isamu Noguchi is history’s most traveled artist.”

Dedicated to artistic experimentation and the integration of all the arts, in addition to sculpture he created gardens, playgrounds, furniture and lighting, ceramics, architecture, and set designs — of which he created several for Martha Graham.

“Everything was sculpture. Any material, any idea without hindrance born into space, I considered sculpture.” Isamu Noguchi

In the 1950s Noguchi designed the first of a series of lamps that would be produced by the traditional Gifu methods of construction, using the inner bark of the mulberry tree wrapped around bamboo ribbing. He called these works akari, meaning both light as illumination as well as conveying the idea of weightlessness. These paper lamps are still ubiquitous in Japan-inspired settings. (And many styles can be purchased in the Museum shop.)

There is a room in the Museum that originally functioned as an Akari showroom, in which are installed examples of these “light sculptures” along with some of Noguchi’s furniture designs.

When Isamu Noguchi was selected to represent the US at the 1986 Venice Biennale, he chose a large work in Carrara marble, Slide Mantra, as the centerpiece of the exhibit. One of his last major public works, the 29-ton Slide Mantra has been a favorite feature of Bayfront Park in Miami Beach since 1991. (There’s another in Sapporo, in black granite).

82 year-old Isamu Noguchi tests his

Slide Mantra, 1986 Venice Biennale

Slide Mantra maquette, (195-85)

Botticino marble

The small smooth white marble maquette (working model) for Slide Mantra is displayed at the museum in a ground-level space that was Noguchi’s garage, where he used to keep his beige Volkswagen Rabbit.

“I am ever mindful of the notion that to discover or rediscover the true meaning of sculpture, the experience of sculpture has to be expanded. Here the tactile quality of sculpture is paramount—a chance for people to slide!” Isamu Noguchi

The Noguchi Museum and Garden attest to his interest in making sculpture everywhere out of everything. He was completely in sync with America’s mid-century belief that design had the power to shape the modern world, and he brought a dual-cultural sensibility to his lasting contribution to Modernism.

Rocks have profound meaning in Japanese philosophy. Longevity. Strength. Permanence. Like the rock he turned to repeatedly as a medium of expression, Isamu Noguchi’s aesthetic is innately timeless.

Noguchi Museum and Garden

9-01 33rd Rd, Long Island City, New York City, NY

718-204-7088

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the search engine that makes it easy to discover more than 1300 art museums, historic houses & artist studios, and sculpture & botanical gardens across the US. Just enter the name of a city or state to see a complete catalog of museums in the area. All in one place: descriptions, locations and links.

Thank you much for this post. I would like to cite the author.

Glad you liked the post, David. You are welcome to reference it.

hi Jane

got some unknown pencil drawing that is signed by Noguchi

how could I contact you?????

Lucky you, Jenny! Unfortunately, we at ArtGeek are not qualified to comment on your Noguchi drawing. I’d recommend that you contact the Noguchi Museum and Garden (info@noguchi.org or 718-204-7088)