Conceptual artist-photographer Vik Muniz is intent on meaningful engagement. “Art is not something you can make yourself,” he says, “— you need a spectator, a viewer, an audience. It is a collaboration.”

In an influential 1967 article titled Paragraphs on Conceptual Art, Sol LeWitt proposed a definition of conceptual art that was widely accepted as doctrine. “In conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work,” he said, meaning that “all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair.” (my italics)

Keeping this in mind whenever I can’t make sense of a piece of conceptual art helps me feel less dense. It reminds me that the problem may not be my lack of perception, but rather that the artist simply lacked a meaningful idea.

In my view, good conceptual art allows that the idea must be accessible to the viewer, and not solely existing in the mind of the conceptualizer. Producing a work that lacks meaning to anyone but the producer seems to me to be nothing more than an act of self-pleasuring.

In an article titled If You Don’t Understand Conceptual Art, It’s Not Your Fault, Isaac Kaplan says, “A bad conceptual work makes you feel that the idea isn’t worth finding. A good one spurs you to keep searching.”

And therein lies the marvel of Vik Muniz’ work.

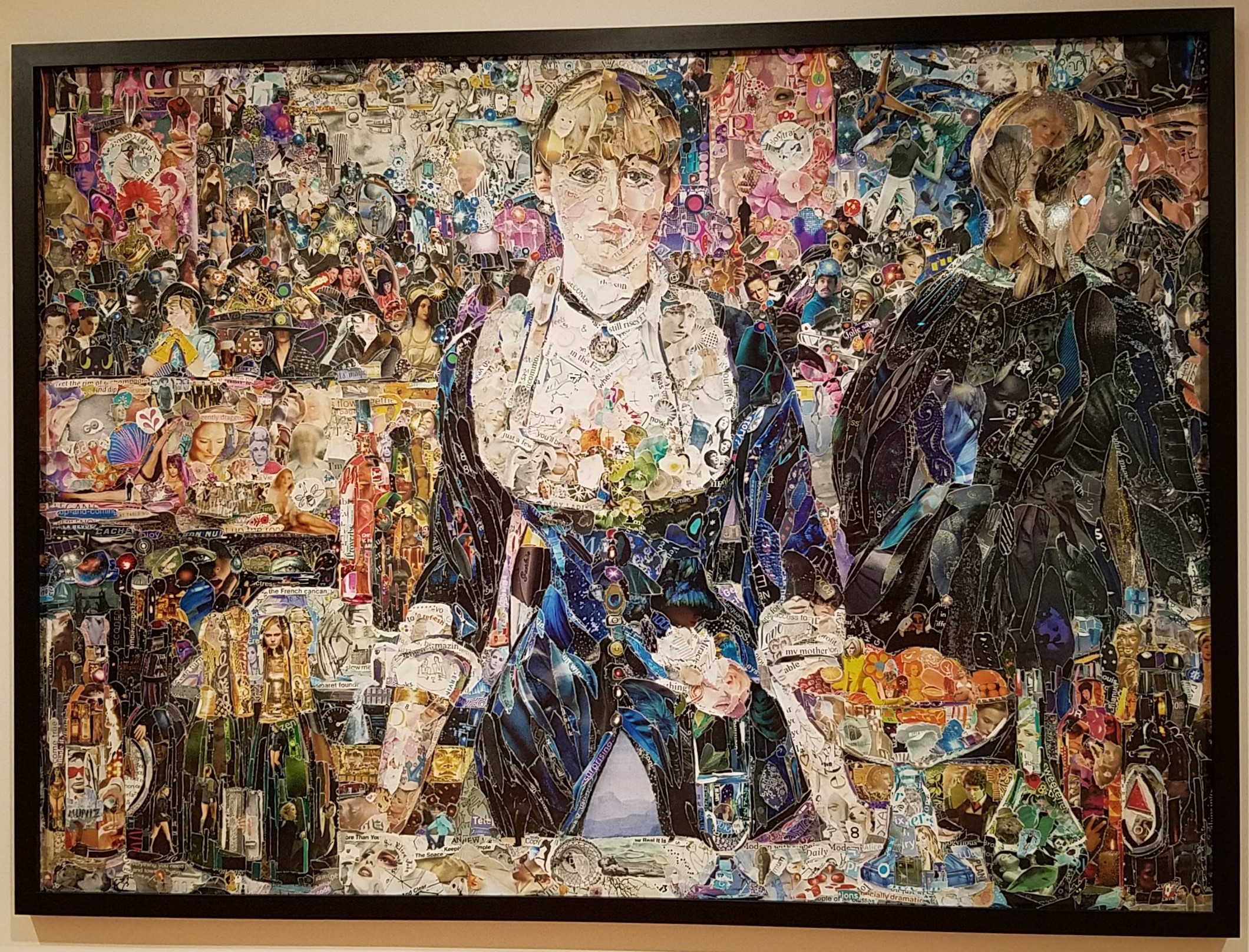

I’m never happier than when I’m completely immersed in art in a conducive museum space. And happy I was, recently, when I had the opportunity to explore Muniz’ work at a mid-career retrospective show at the new Sarasota Art Museum. (Vik Muniz, on through March 8, 2020).

Labelled a “conceptual artist-photographer,” Brazilian-born Muniz believes that “Art has the power of changing the way you look at things and challenging your vision of the world.”

With this as a motivating precept, it comes as no surprise that Vik Muniz’ art communicates. His concepts don’t need tortuous explanations to redeem meaning. They instantly engage, emerging with wit or poignancy or reference to the familiar.

Art Historical Quotations

Throughout time, artists have copied the work of artists who came before, and Muniz carries on this tradition, recreating well-known paintings by some of art history’s great artists. He also draws on another tradition, specific to Brazilian art, called antropofagia, which is the “cannibalization” or reference to European subjects and forms.

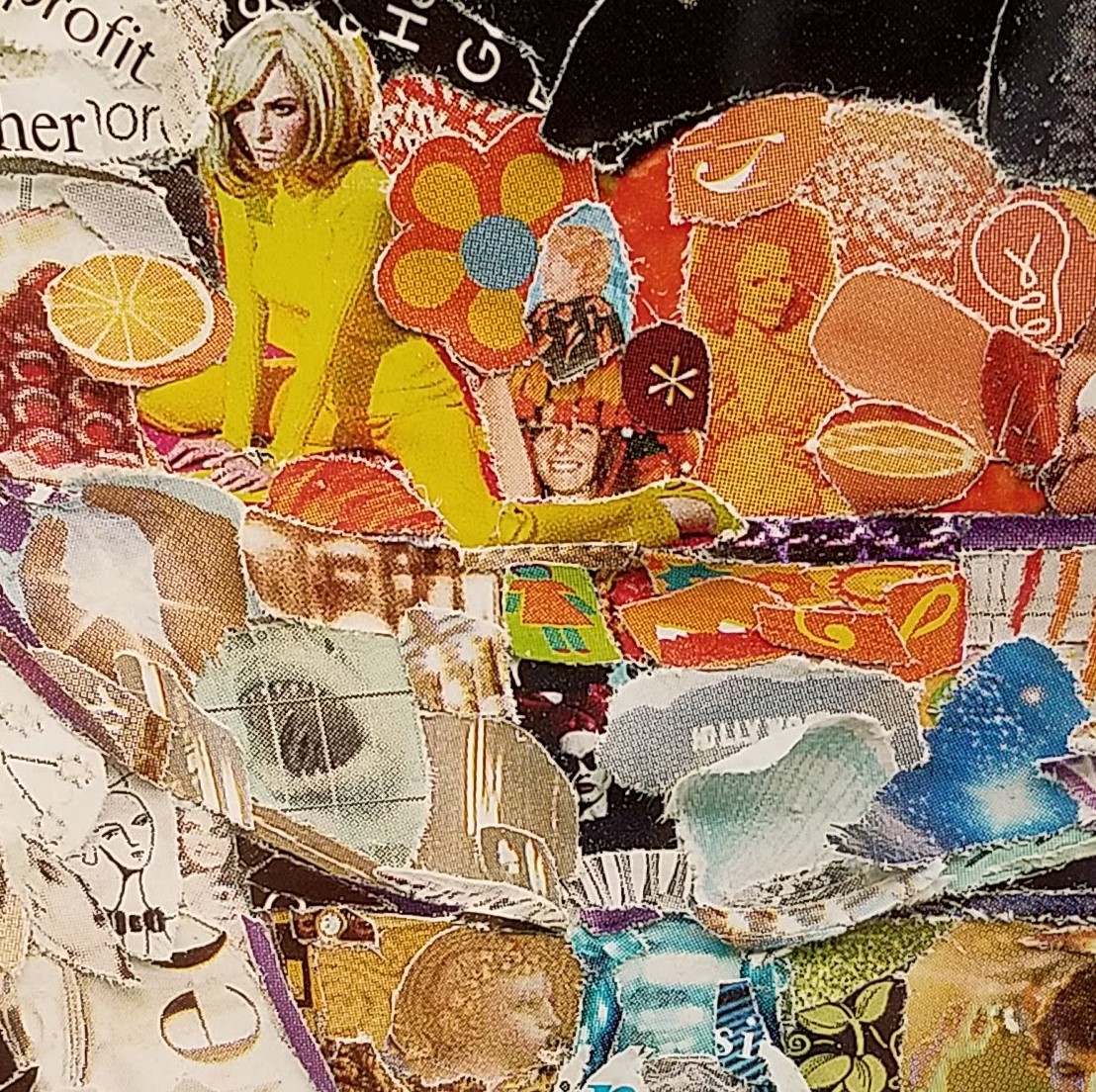

In his From Pictures of Magazines series, original copies reinterpret famous works using a unique and diverse mix of materials.

Courtesy of Galerie Xippas, Paris

In Zebra, after George Stubbs, for example, Muniz copied Stubbs’ 1763 painting, Zebra, creating a collage with images clipped from magazines, which he then photographed and enlarged. Seen together, the two are not at all the same, yet the Muniz Zebra immediately conjures an image of the Stubbs painting to anyone who is familiar with it. The original and the recreation connect in the visual memory of the observer.

“One thing that is important is that when you are working towards this meeting point you have to be perfectly aware of what the viewer is bringing to the bargain,” Muniz says. “In this sense, working with archetypes, stereotypes or icons is very useful because you know people have at least seen things that look like that before. […] The picture is just a composite of everything you’ve ever seen that is zebra-like or zebra-related so when you look at this picture you are looking at it through the filter of every single zebra you’ve seen in your entire life, and it’s still hard to focus because the picture is composed of a myriad of little distractions that are non-zebra-like.”

Indeed, as you look closely, you see more familiar images, smaller snippets of recognition that recompose your thinking about what you’re looking at. In this dizzying array of details, you begin to sense the degree to which your personal memories are born of a collective cultural history.

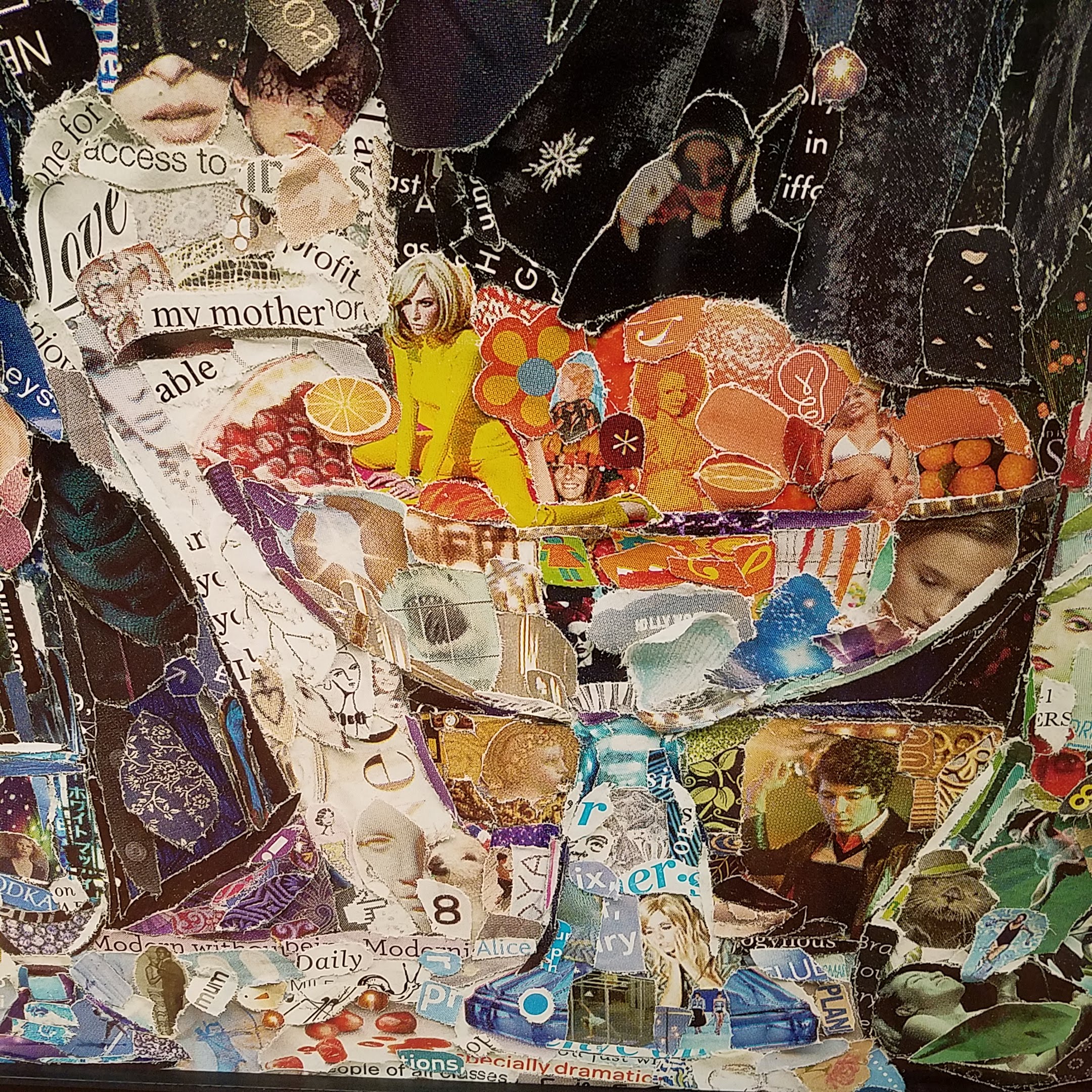

Not familiar with Stubbs’ Zebra? Here’s perhaps a more familiar recreation: A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, after Edouard Manet.

Again so similar and so much not the same. Again replete with small snippets of recognition that refocus your concept of what you are seeing.

Clearly, a bowl of fruit is not always just a bowl of fruit.

From the larger art-historical quotations — which seem, as one critic put it, “like some kind of rag picker’s folk art” — to the profusion of detail, Munoz’ collages are comforting, stimulating, amusing … and somewhat unsettling.

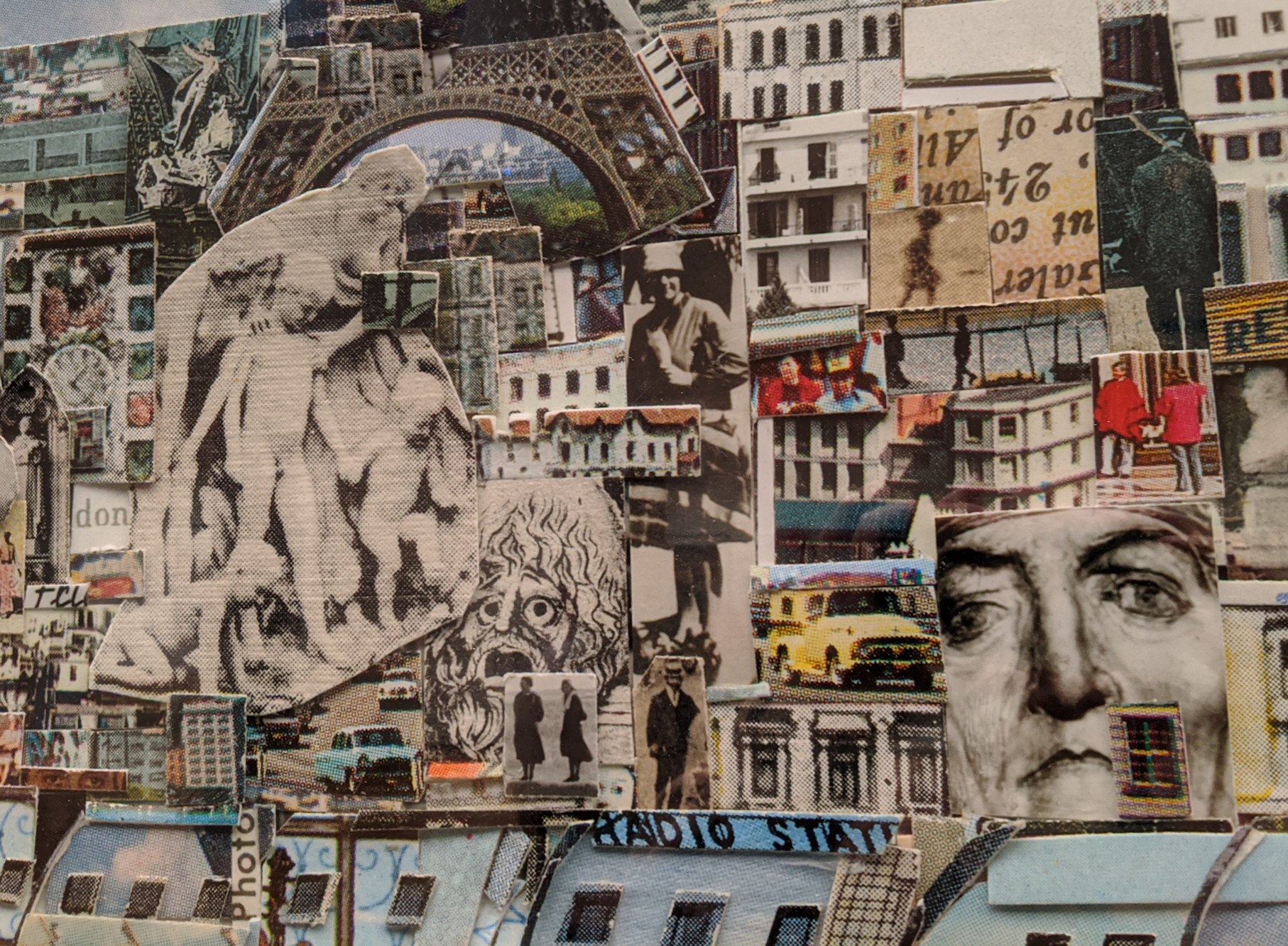

Pictures of Garbage

Having grown up in poverty in Brazil, Muniz is now actively involved in educational and social justice intiatives there. Sensitive to the plight of the catadores (trash pickers) in the world’s largest landfill, in Rio de Janeiro, he collaborted with them to create a powerful series of portrait images. The pictures reveal both the dignity and despair of these impoverished people, and transform documentation into art.

The catadores helped select garbage to arrange into portraits of themselves. Muniz created the portrait compositions on the floor of a large warehouse, and — with his camera on a platform raised high above by a crane — he then created a permanent record of each of them.

Vik Muniz, Marat (Sebastiao) Pictures of Garbage, 2008 Chromogenic print

Jacques-Louis David,

The Death of Marat, 1793

Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium

Again, some of the poses recall iconic art images, like Jacques-Louis David’s 1793 The Death of Marat.

Proceeds from the sale of the Pictures of Garbage prints were donated to the catadores and to the co-operative they founded to improve life in their community.

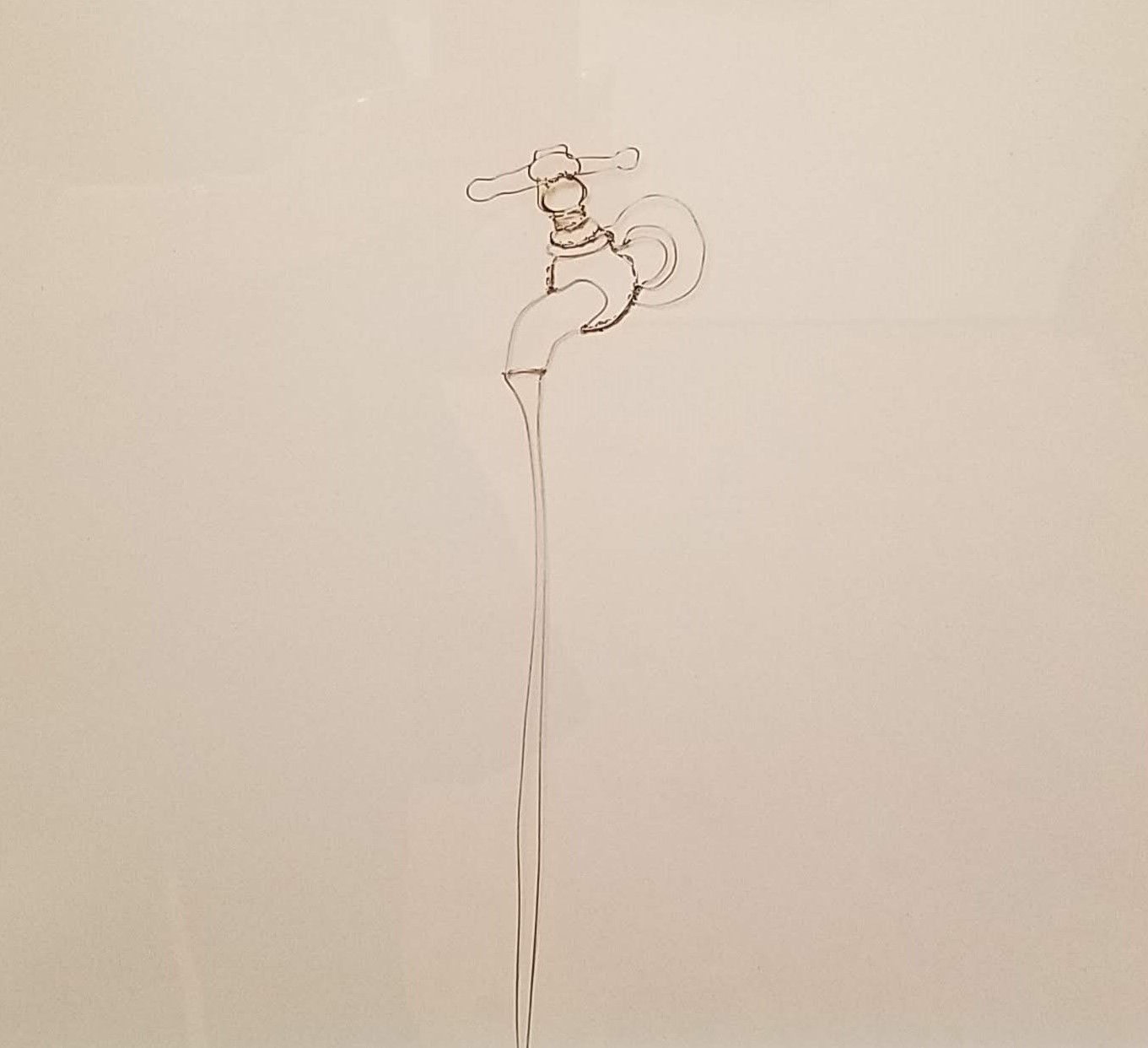

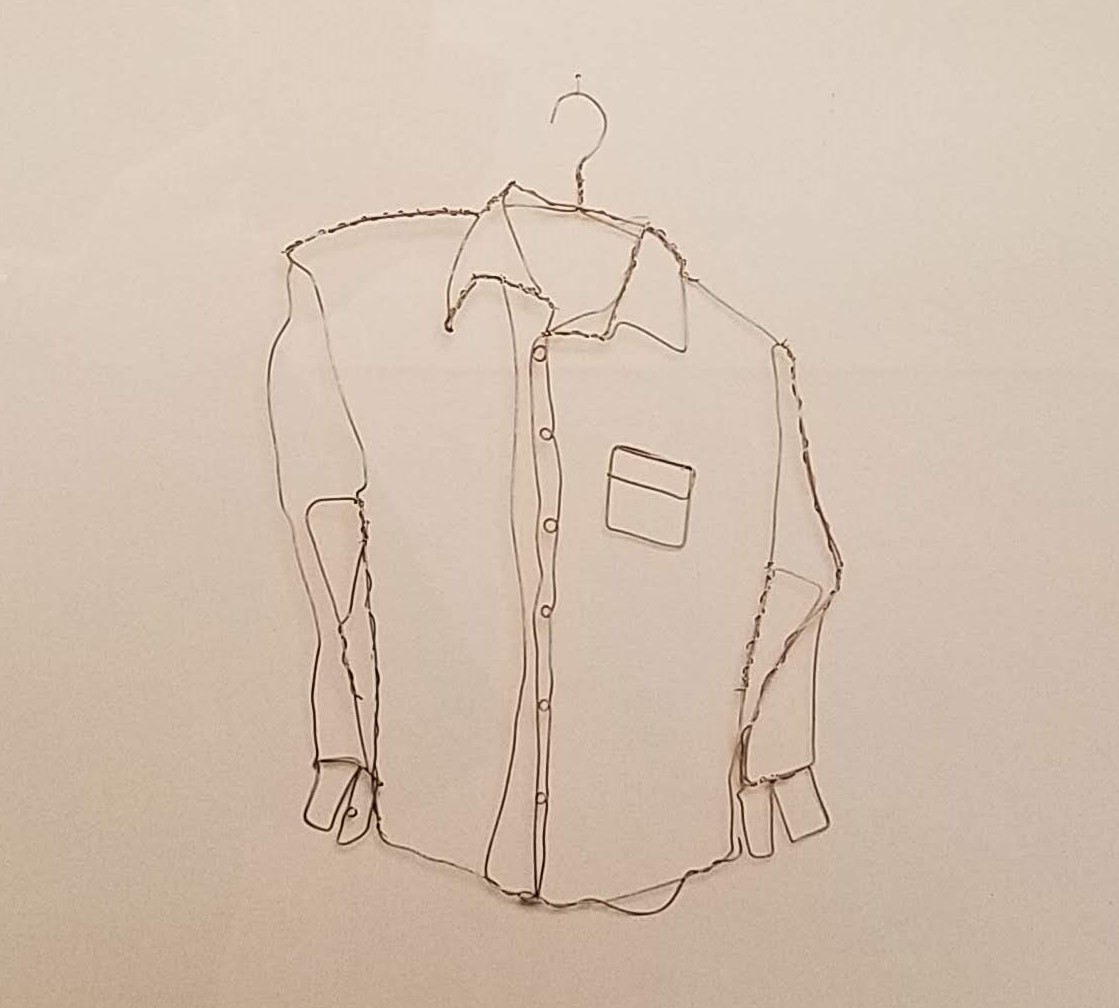

In a 2016 interview, Muniz said “I want to create the worst possible illusions so it doesn’t really fool people, but give people a measure of their own belief. It makes them aware of how much they need to be fooled in order to understand the world around them.” And so, he created these lovely little line drawings — which aren’t line drawings at all.

Vik Muniz, Faucet from Pictures of Wire, 1994; Toned gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the artist

Vik Muniz, The White Shirt I from Pictures of Wire, 1995; Toned gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist

Vik Muniz loves to play with scale, to produce illusions and create metaphors to provoke the questioning that’s necessary to really understand what you’re looking at. His are not pictures to look at passively. He says about his images, “when you look at them, the important thing is that the picture in your head and the picture that I made meet halfway.”

This bit of curatorial text is a nice way to wrap up: “Vik Muniz’ unparalleled mind is like a magical curiosity cabinet, endlessly gathering interesting things and generating new perspectives. He helps us see the world anew. Few artists embody such a playful sense of wonder and discovery as Vik.”

Indeed, Muniz’ textured photographs transform one thing into another, taking us from the moment to the memory and back again.

Vik Muniz, on through March 8, 2020

The Sarasota Museum of Art

891 S Tamiami Trail, Sarasota, FL

941-309-7662

Hmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a little trip?

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the search engine that makes it easy to discover more than 1300 art museums, historic houses & artist studios, and sculpture & botanical gardens across the US.