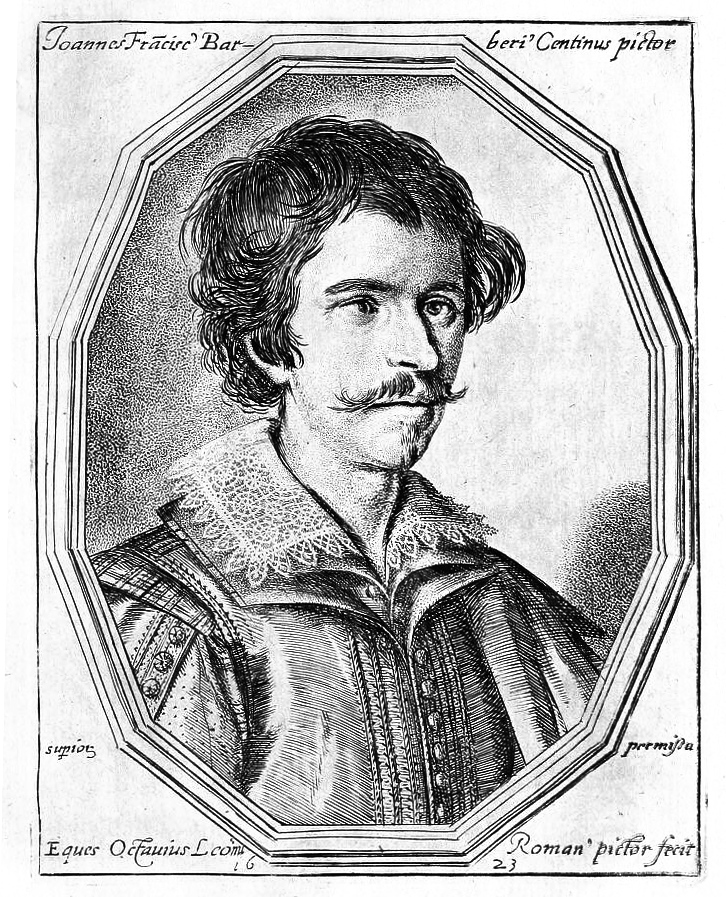

Depending on the dictionary you use, his nickname translates to either “Squinty” or “Cross-Eyed.” His contemporary biographer claims that this condition was caused by having been awakened as an infant by a sudden loud noise, and it “left one of his eyes permanently fixed at an angle in its socket.”

In spite of his in-turned eye – or perhaps because of it? – Guercino is regarded as one of the greatest Italian draftsmen of the 17th century, widely admired for his energetic, probing drawings. He showed a remarkable ability to create a sense of depth in his work, and some speculate that his perception of light and shade was enhanced by a compensating acuity in his healthy eye.

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, known as Guercino (1591– 1666), was arguably the most interesting and diverse draftsman of the Italian Baroque era, a natural virtuoso who created brilliant drawings in a broad range of media.

Bird-catching was sometimes associated with seduction or courtship, and uccello (bird) is Italian slang for penis. The position of the birdcage suggests this is more than just a simple image of a tradesman.

The Morgan Library & Museum owns more than thirty-five works by Guercino. Supplemented by a pair of loans from New York private collections, they are the subject of a focused exhibition at the Morgan. Guercino: Virtuoso Draftsman is on view through February 2, 2020. The exhibition includes sheets of drawings from throughout the artist’s career.

Installation view at The Morgan Library and Museum

Apprenticed at age nine to a local artist in his hometown of Cento, by his late teens he was in Bologna studying the work of the Carracci. The influence of that exceptional family of artists on Guercino is evidenced in the show by the engaging figures he drew from everyday life, as well as his brilliant caricatures.

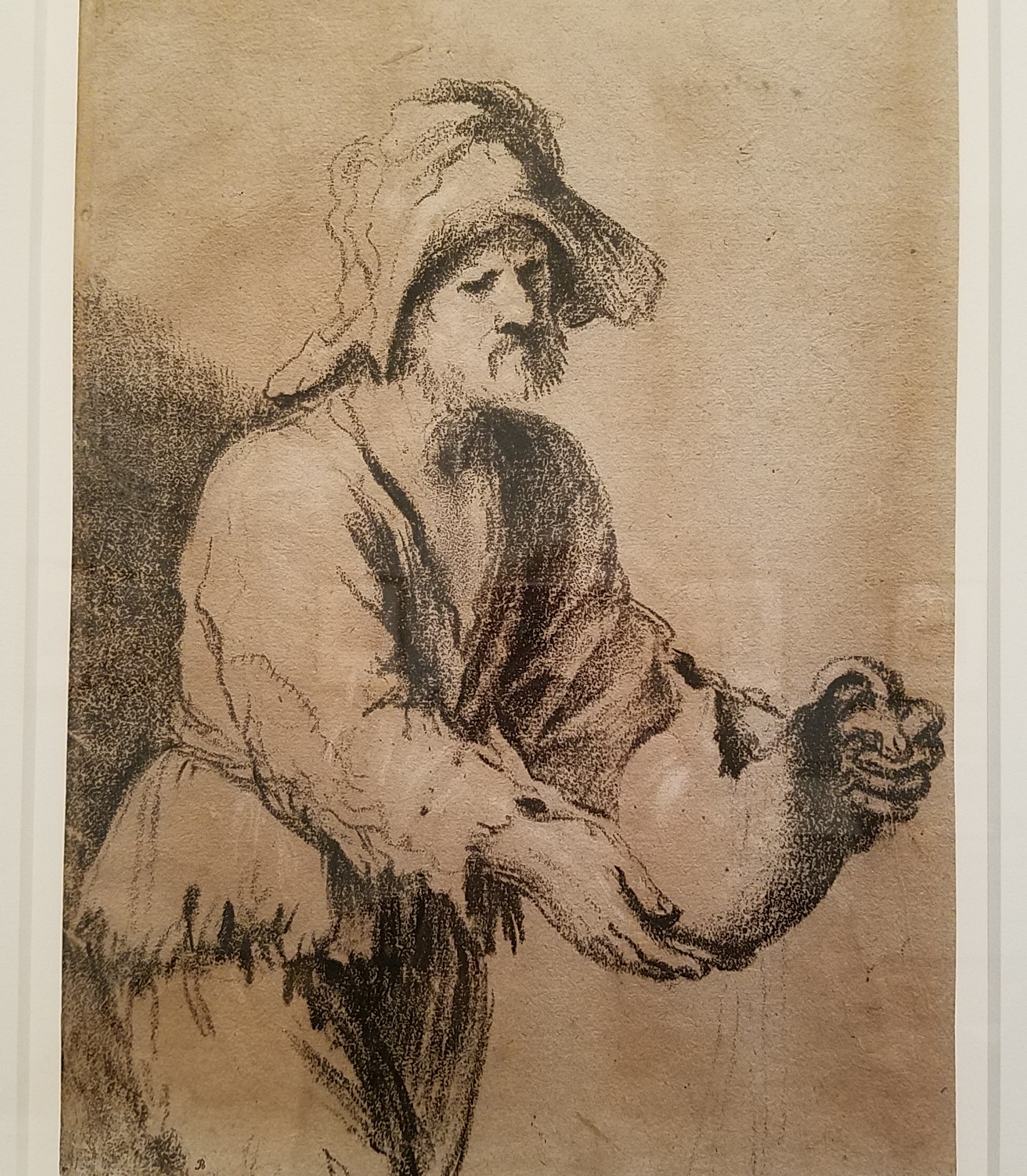

Charcoal, dipped in gum solution, and white chalk, on brown paper

Guercino seems to have shown a paticular kindness toward the less privileged. Adjacent wall text tells us that his biographer, Malvasia, “noted that the artist was ‘affectionate to the poor, who flocked around him whenever he left his house, as if he were their father …'” Malvasia admired Guercino for being “humble, well-mannered, honest, respectful, chaste, and agreeable.” (So unlike his contemporary, Caravaggio!)

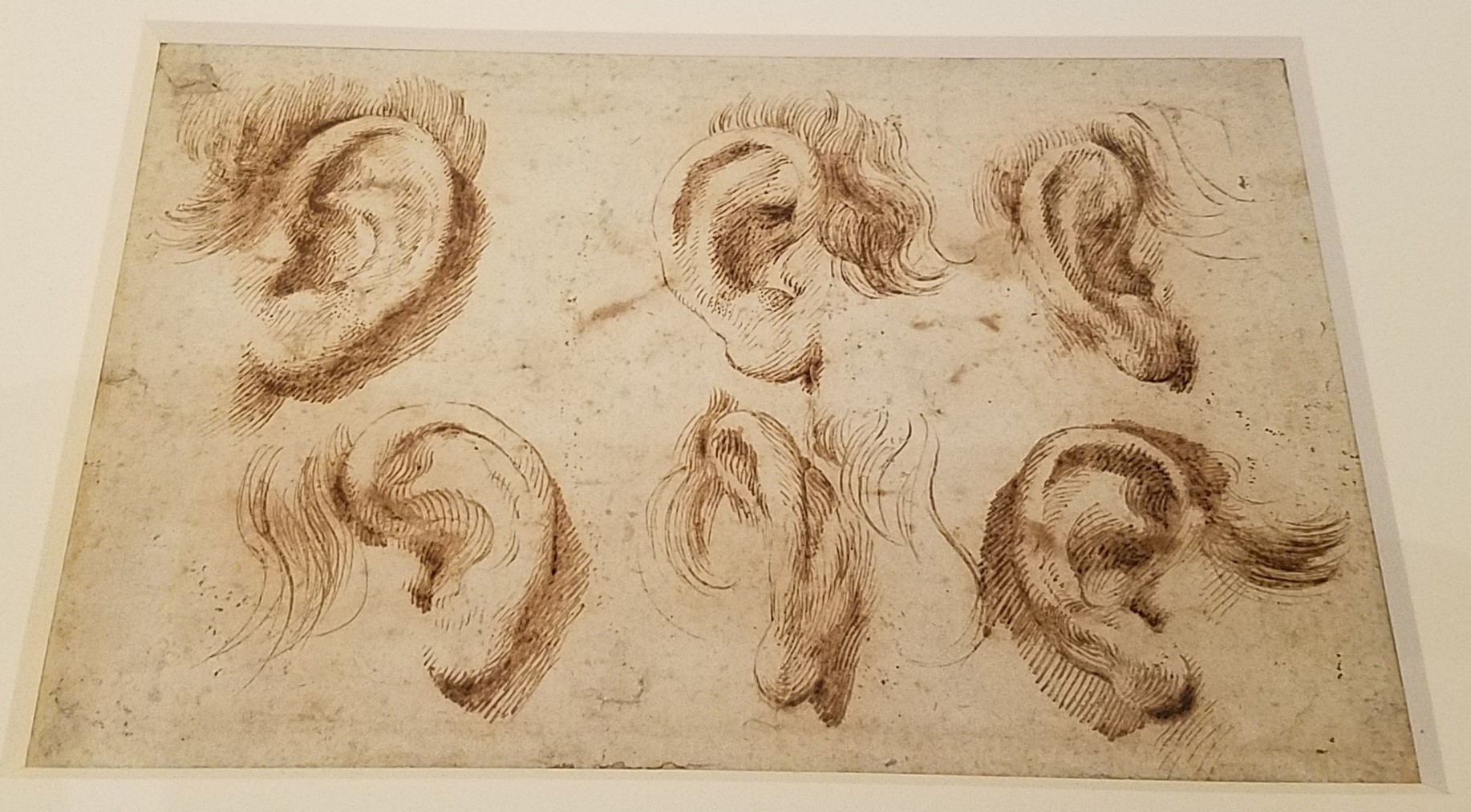

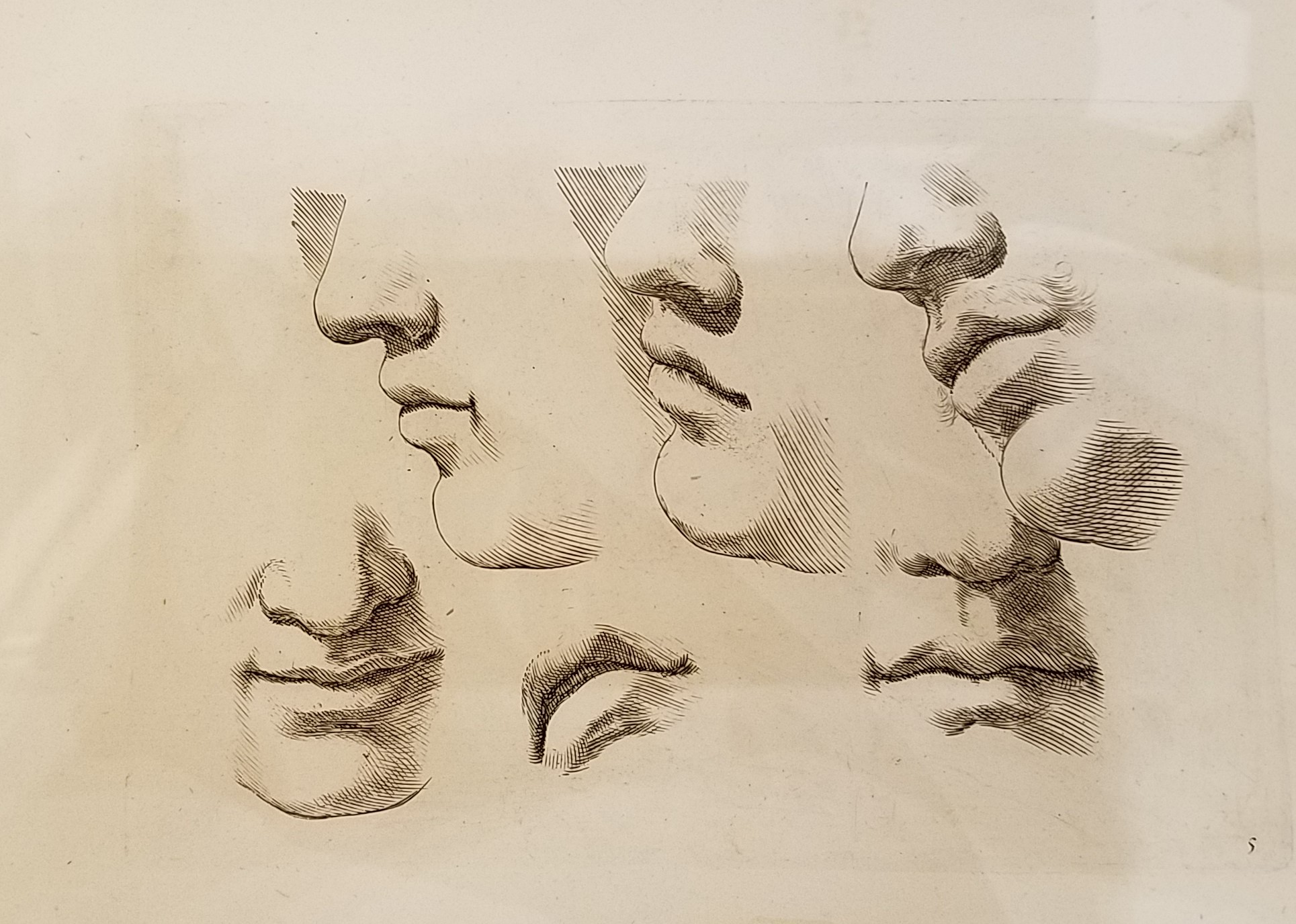

Guercino’s skill as a draftsman was recognized early, and he was soon in demand as a teacher. He opened an Accademia del nudo, which grew to twenty-three students who honed their skill by drawing from nude models. But by 1617 he was accepting so many major painting commissions that he had become too busy to teach. It may have been this that prompted Guercino’s patron, Padre Antonio Mirandola, to suggest that he create a set of drawings for the instruction of young painters. He did so, and in 1619 his series of 22 sheets of anatomical drawings were engraved by Oliviero Gatti. The publication was popular from the get-go and several subsequent editions were produced.

Pen and brown ink on laid paper

Although the volume was not given a formal title, it is known as Guercino’s Libro dei Disegni. The Morgan recently acquired two sheets from Guercino’s original set of drawings, and they are included in the exhibition.

Pen and brown ink on laid paper

A painter by trade, for Guercino drawing was an integral part of his process. When awarded a commission, he would explore the desired subject in a series of studies. He would draw figures in different arrangements, make close-up studies of the principle figures, and explore facial expressions and body language to convey the psychological aspects of the scene. Then, as he put paint to canvas, he would often change everything again. Drawing was for him a way of thinking about the subject and testing ideas, rather than part of a linear compositional methodology.

Tracing his career, the preparatory drawings in the Morgan’s exhibition include studies made in connection with his earliest altarpieces as well as for his later masterpieces. Multiple studies for several individual projects show us the process Guercino went through as he developed his ideas.

Guercino possessed extraordinary talents when it came to the manipulation of materials. The furious vitality of his pen work is his most recognizable stylistic trait, perhaps best seen in looping, calligraphic pen lines that do not depict drapery folds so much as they convey a sense of fluttering cloth.

Pen and brown ink, with brown wash, on paper.

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of János Scholz, 1977.49.

Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2019

After this energetic sketching with the pen, he would typically take up a brush, clarifying a design or even seeming to sculpt forms with multiple layers of wash— sometimes using thin, fluid, transparent washes, and other times thick, more opaque washes. These multiple layers of wash created dramatic chiaroscuro effects.

Red chalk on laid paper. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan in 1909

Later in his career, he more often made use of red chalk, creating luminous, delicate studies. Occasionally, he would combine pen, wash, and chalk in highly finished drawings that were complete works in their own right.

Red chalk on paper

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913) in 1909

Guercino’s fame grew throughout the later decades of his career. Among the drawings at the Morgan are studies for large painted altarpieces that were sent farther afield, to Turin and Verona. He never wanted for work: he continued to receive commissions from the popes and cardinals in Rome and also made paintings for a host of royal patrons.

But drawing remained the basic operative element of Guercino’s artistic output. It is of little surprise that an artist so perpetually engaged in the exploration of the world through drawing has left behind a body of work that continues to delight and fascinate us today.

Despite their fragility, it is estimated that about 40% of Guercino’s works on paper still survive. It is thought that this may be an unparalleled percentage among 16th and 17th century artists. Consider, for example, that only about 1% of Michelangelo’s drawings are thought to survive.

“Guercino was one of the most brilliant draftsman in Baroque Italy, a natural virtuoso whose genius is equally clear in the quickest pen sketch and in the most refined chalk drawing,” says Colin B. Bailey, Director of the Morgan Library & Museum. “I am delighted that audiences will be able to see his talents first hand and explore the Morgan Library & Museum’s unparalleled holdings of Guercino’s work in this exhibition.”

Hmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a little trip?

Can’t make it? Or even if you can — the small (80 pages) companion catalogue, Guercino: Virtuoso Draftsman, delves into this artist’s graphic work, from his early genre studies and caricatures, to the dense and dynamic preparatory studies for his paintings, and on to highly finished chalk drawings and landscapes that were ends in themselves.

An introductory essay on Guercino as a draftsman is followed by entries on his drawings in the Morgan’s collection which have never before been exhibited or published as a group.

“The drawings come from every period of his career and John Marciari writes meticulously on each one.”

(The Art Newspaper)

The Morgan Library & Museum

225 Madison Avenue, at E. 36th St, New York City, NY

212-685-0008

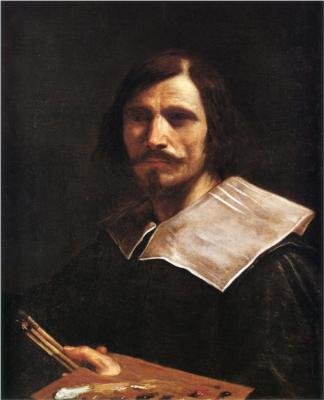

Featured header image: Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, known as Guercino (1591– 1666), Self-Portrait. (circa 1624 -6). Oil on canvas, 641 x 521 mm (25 1/4 x 20 1/2″). Private Collection, courtesy Richard L. Feigen & Co. Sydney

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the search engine that makes it easy to discover more than 1300 art museums, historic houses and artist studios, and gardens across the US.