A major exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum explores Édouard Manet’s later years — after his rise to notoriety in the 1860s and the formal launch of the Impressionist movement in the early 1870s.

Édouard Manet (1832-1883) is best known today for large-scale paintings that once were provocative — paintings which challenged the old masters and academic tradition and sent shockwaves through the French art world in the early 1860s. In the late 1870s and early 1880s, however, he shifted his focus and produced a different — though no less radical — body of work.

Manet and Modern Beauty (through January 12, 2020) features more than 90 of Manet’s later works. On view is an array of stylish portraits, luscious still lifes, delicate pastels, genre scenes of suburban gardens and Parisian cafes, and portraits of favorite actresses and models, bourgeois women of his acquaintance, his wife, and his male friends. The works sparkle with an insistent – perhaps even defiant – sense of life. Many iconic oil paintings — including the Getty’s recently-acquired Jeanne (Spring) — as well as pastels and intimate watercolors, provide a fresh look at this ever-popular artist.

Drs. Robert N. Mayer and Debra E. Weese- Mayer Family Collection, Chicago

“Manet is a titan of modern art, but most art historical narratives about his achievement focus on his early and mid-career work,” says Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. “Many of his later paintings are of extraordinary beauty, executed at the height of his artistic prowess—despite the fact that he was already afflicted with the illness that would lead to his early death.” [Manet died in 1883, at the age of 51. Long suffering with complications from syphilis and rheumatism, in April his gangrenous left foot was amputated, and he died eleven days later.]

Declining health forced him to adjust his working habits: during the last six or seven years of his life his output was generally more intimate in both scale and subject, focusing on fashionable scenes of Parisian life and the stylish women, and sometimes men, of his acquaintance.

Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, H. O. Havemeyer Collection

Too often dismissed as superficial by critics, these later works provide valuable testimony to Manet’s elegant social circle and suggest a radical new alignment of modern art with fashionable femininity while recording the artist’s unapologetic embrace of beauty and visual pleasure in the face of death.

This landmark exhibition is divided into five sections—La Vie Moderne, Portraits of an Era, The Four Seasons Project, Manet at Bellevue, and Flowers, Fruits, and Gardens.

The first of these considers a notable solo show in 1880, when Manet was invited to exhibit in the gallery affiliated with La Vie Moderne, a new fashion and culture magazine. Introducing the public to his provocative cabaret, bar, and boudoir scenes and to his pastel portraits, this exhibition marked a new beginning for Manet. Numerous works shown at the Vie Moderne gallery are on display in this section.

18 5/8 × 15 3/8 in. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD

The following section— Portraits of an Era—demonstrates the importance of portraiture to Manet’s identity as a painter of modern life. Not simply intent on recording individual likenesses, he aimed to capture the essence of his epoch by portraying representative social types—the chic parisienne or fashionable dandy, for instance—in their various modes of dress and deportment.

The ArtInstitute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn Memorial Collection

This section also explores Manet’s emerging practice of portraiture in pastel, a medium closely associated with his Impressionist colleagues Edgar Degas and Berthe Morisot. Using these dry sticks of pure color did not require the same lengthy and laborious studio procedures as oil painting, and between about 1878 and his death, Manet turned out close to 100 pastels, the great majority of them portraits.

“Unlike Titian and Rembrandt—or indeed, his friends Monet and Degas—Manet didn’t live long enough to develop a late style, but the work of his last years is still distinct from what preceded it, characterized by a new lightness of spirit, of palette, and often of touch,” says Emily Beeny, associate curator of drawings at the Getty Museum. “We see a new interest in watercolor and pastel–media that allowed him to work more quickly than he could in oils. But above all we see a new interest in capturing fleeting pleasures on the wing, making permanent the impermanent.

Pastel on canvas, 21 9/16 × 13 7/8 in.

Saint Louis Art Museum, Funds given by John Merril Olin

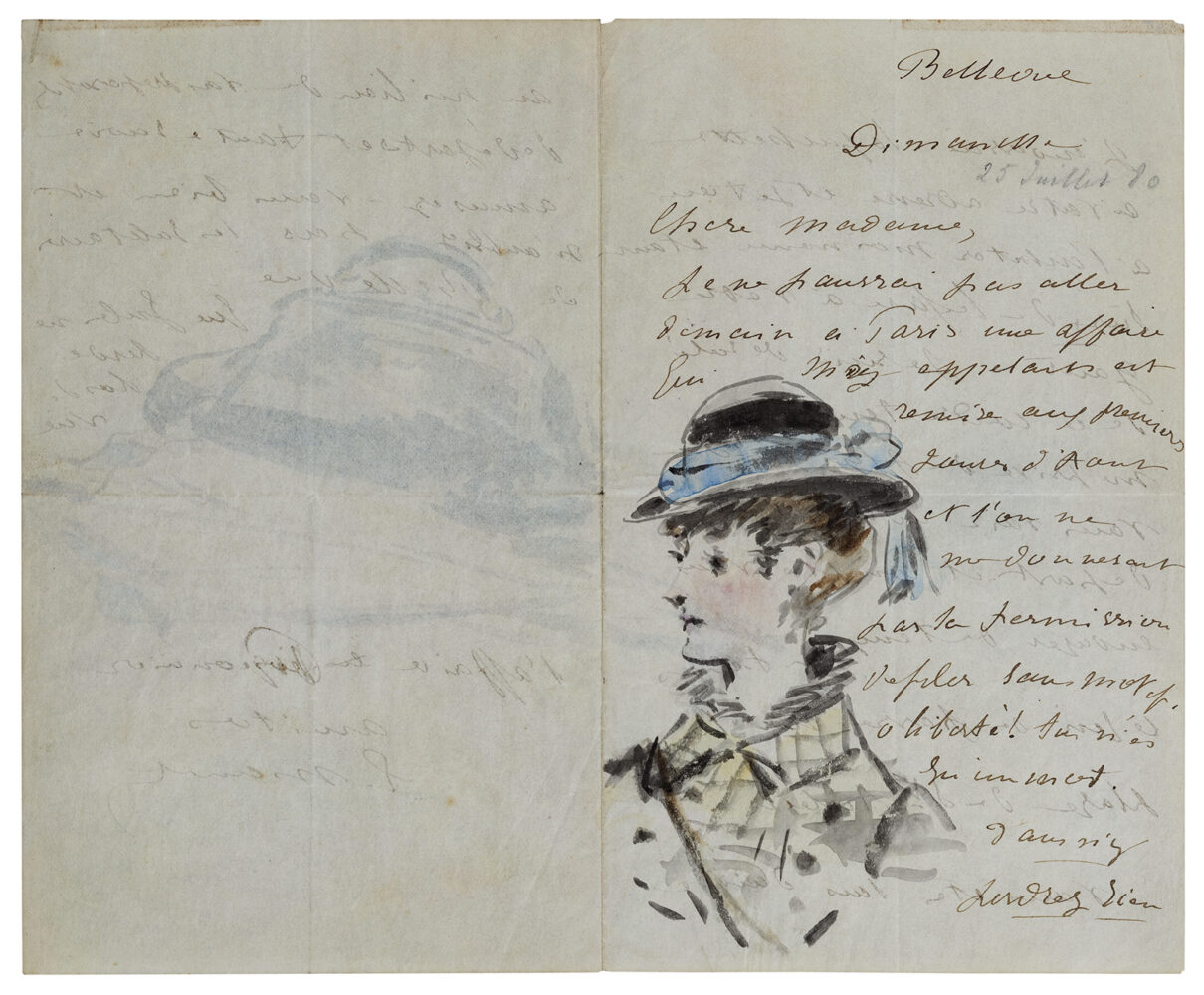

Fashions obviously change; youthful beauty fades; flowers wilt; and in this sense the late production–all those pretty girls and flowers, all those watercolor hats and plums brushed into the margins of his letters, all those bright, little pictures–are also about impermanence. Seen as the work of a dying artist, they give us a vivid sense of beauty snatched from the jaws of time, beauty embraced in the teeth of acute physical suffering.”

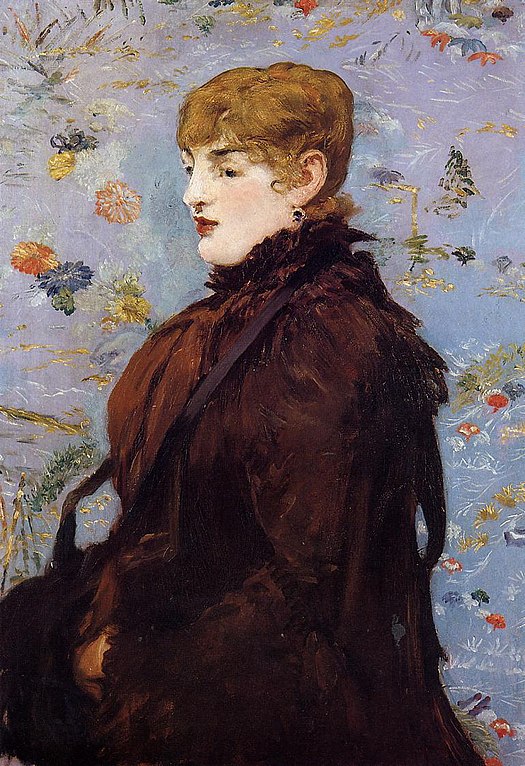

Manet intended for his 1882 Salon painting Jeanne, which he also called Spring, to be the first in a series of four seasons, each in the guise of a stylish parisienne. Responding to trends in contemporary painting, popular illustration, and fashion advertising, Manet modernized a time-honored subject in European art. Doing away with the conventional symbolic trappings (a dove for spring, fallen leaves for autumn, and so on), he focused exclusively on the model, her chic apparel, and her decorative surroundings. More than the perennial rhythms of nature, Manet’s principal concern was the modern fashion cycle. Unfortunately, Manet never completed his seasonal cycle, painting only Autumn (1881 or 1882) after Spring.

28 3/8 × 20 1/4 in. Musée des beaux-arts, Nancy, France. Photo: P. Mignot

This exhibition reunites the two paintings for the first time in nearly forty years. “Jeanne was an unalloyed critical success for Manet, making it a rare exception in a career dogged by scandal, controversy, and disappointment,” notes Scott Allan, associate curator of paintings at the Getty Museum. “Although it has been overshadowed by A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, its famous companion at the 1882 Salon, Jeanne occupies the heart of our exhibition because it perfectly epitomizes Manet’s consuming late-career interest in fashion, flowers, and seductive Parisian femininity, which was absolutely central to his conception of the painting of modern life.

It is worth recalling that Manet’s friend Baudelaire began his famous essay ‘The Painter of Modern Life’ with a section entitled ‘Beauty, Fashion, and Happiness.’ That for us is the perfect epigraph for Jeanne and for this exhibition, which emphasizes the passionate attachments, worldly, sensual and aesthetic, of an ailing artist who would die before his time.”

Manet at Bellevue focuses on Manet’s time in the spa town of Bellevue in June of 1880 where he was sent to undergo a course of bathing treatments prescribed by his doctors. Though accompanied by his family, Manet quickly grew lonely and bored with life in the “country,” as he called it, and began to fill the margins of his letters to friends and colleagues back in Paris or on vacation at the beach in Normandy with watercolor illustrations: plums, cats, flowers, and so on. In this section is the largest group of Manet’s adorned watercolor letters ever exhibited outside France.

Paralysis of his left leg confined him to his apartment and studio; he no longer visited friends or frequented cafes. Instead, café life came to him, as friends and acquaintances flocked to his studio to gossip and watch him work. Visitors came bearing flowers, which Manet adored and painted.

These final still lifes are among the most beautiful pictures in his oeuvre, evidence of his evolution as a painter to the very last.

Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA

The final section—Flowers, Fruit, and Gardens—follows his final years. As Manet’s health continued to deteriorate, the painting of flowers, fruit, and garden scenes increasingly occupied his time. He spent his last two summers outside the city, taking rest cures at Versailles in 1881 and Rueil in 1882 where he painted the gardens of his rental houses and pined for Paris.

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Felton Bequest, 1926 Photo: Garry Sommerfeld

The principal aim of the curators of Manet and Modern Beauty is to present the artist’s late work in a positive light, as an evolution of his practice that merits serious attention and rewards close looking. “We can see in these works a culmination of Manet’s ambition to style himself ‘the painter of modern life,’ as formulated in an 1863 essay by his friend Charles Baudelaire.

The Iris, the Getty newsletter

The critical force of Baudelaire’s essay comes from its upending of hierarchies. Minor genres, marginal modes of illustration, and passing fashions take center stage, replacing dusty academic notions of “ideal” or “eternal” beauty. “Modern” beauty, for Baudelaire, found its vitality and character in the fleeting, superficial, and contingent. Fashion was Baudelaire’s defining metaphor for modernity, and the sheer artifice of the feminine toilette in particular offered an irresistible subject to a new breed of artist, passionately dedicated to the transient beauty of the modern city.

Baudelaire titled the first section of his essay “Beauty, Fashion, and Happiness.” This, we think, is a fine and poignant motto for Manet’s last works too. Fresh, intimate, and unapologetically pretty, the late work demonstrates his defiant embrace of beauty and pleasure in the teeth of acute physical suffering.

Manet and Modern Beauty is on at the Getty Center through Jan 12, 2020

Hmmm …. maybe it’s time to plan a little trip?

J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center

1200 Getty Center Dr, Los Angeles, CA

310-440-7300

Featured headline image: Édouard Manet (French, 1832 – 1883), Jeanne (Spring), 1881; Oil on canvas 74 × 51.5 cm (29 1/8 × 20 1/4 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA

Art Things Considered is an art travel blog for art geeks, by ArtGeek.art — the search engine to easily find more than 1300 art museums, historic houses, artist studios, and gardens across the US.

Enjoyed this sight, but unable to travel there…but have a VERY OLD 12×16 landscape

Heavy paint strokes on very old Canvas in plain wooden frame, looks like could very well be

Ma net signed . Left to me by my brother, who lived in VIRGINIA BEACH , Va…maybe 25 yrs. ago, been in my Attic sense then…given to him as a gift yrs before that…

IF You know of anyone , or an Art Museum that would be interested in it ….at a reasonable price, for them and me …

Brenda, your best bet would be to contact an art museum or a reputable art dealer to ask about this. Or perhaps an art auction house. Good luck.

Was very surprised to learn a lot of the background of both Monet and Manet……

I really enjoyed this sight, I found while browsing , thank you guys. I have an interest now

to learn more about other artists as well. Thanks

Thank you for your comment, Brenda. So pleased that you like our blog!