Rediscovered after nearly 170 years missing, an important Delacroix painting has found a new home.

The whereabouts of a masterwork by 19th-century French painter Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) were unknown between the time of its recorded sale in 1850 until 2018, when it was discovered in a Paris apartment. Of course the owner knew it was there, but she didn’t really know what she had. The excitement of discovery began when she invited gallerist Philippe Mendes to have a look at it for authentication.

After extensive research and radiographic study, the painting was authenticated by Delacroix expert Virginie Cauchi-Fatiga. It was shown publicly for the first time in June 2019 at Galerie Philippe Mendes, Paris.

It turns out that the work is the first of three versions of Women of Algiers in Their Apartment that Delacroix painted. The second version, his acclaimed masterpiece Femmes d’Alger (1834) held by the Louvre, toured last year as part of the Delacroix retrospective exhibition which was co-organized by the Louvre and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The third painting of this scene — created fifteen years later — is held in the collecton of the Musee Fabre in Montpellier, France.

The former owner of the rediscovered canvas decided to sell it, and “after months of speculation about the destination of this truly extraordinary painting, Delacroix’s first, long-lost Femmes d’Alger will have a public and permanent home in Houston,” said Gary Tinterow, Director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. “Women of Algiers in Their Apartment is a landmark addition to our collections,” he added.

The painting showing two women in an ornate, dimly lit interior, is from a pivotal period in Delacroix’s evolution as one of the great Romantic artists of his time. Shortly after France invaded North Africa in 1830, Delacroix, then 32, joined a diplomatic mission that was intended to establish friendly relations and negotiate a treaty with the Sultan.

Arriving in Tangiers, Morocco in January 1832, Delacroix was captivated by the atmosphere, the colours, the objects, the people, and the architecture of this exotic world. He recorded everything he saw in his journals, and during the six-month trip he filled seven large sketchbooks and created an album of eighteen watercolours.

King Louis Phillipe assigned the young diplomat Charles de Mornay to head the mission. At that time it was common to take artists along to visually document the journey.

Delacroix’s participation came about by virtue of his social connections. When Delacroix was studying under Pierre Guérin, he had become friends with Henri Duponchel, a fellow student who ran in the same circle as Mornay’s mistress, the actress Mademoiselle Mars. Unable to go himself, Duponchel recommended Delacroix for the assignment, in what proved to be a major turning point in Delacroix’s career.

Although he was invited into Jewish households to sketch, and his journal recounts in detail the clothing, interior décor, and festivities of the Jewish community, he found it significantly more difficult to sketch Arabic women, due to religious restrictions. He attempted to sketch them from a distance, but was often seen by women hanging washing on roof terraces who quickly alerted their husbands.

Delacroix returned home via Algeria, where he stayed for only a few days. By a stroke of good fortune, he met a merchant who gave him brief access to his private harem. Delacroix was able to create two small sketches while inside the inner sanctum.

The head of the dipomatic mission, the Comte de Mornay, would subsequently commission Delacroix to paint his portrait, and he acquired the first version of Women of Algiers. He sold it in 1850, after which it disappeared from public record.

The scene in the first Women of Algiers shows a woman at the left of the canvas seated on the floor, reclining with her right arm propped on a patterned cushion. Her draped robe is set off by a jeweled necklace and rings. The woman’s maidservant, at right, turns back as she strides past, as if to glance at or respond to her mistress. The golden ochre of the maidservant’s skirt and turban echo the other woman’s robe.

The surface of the painting glints with passages of greens, auburn, and sapphire blue, colors that attest to the profound and enduring influence that the light and colors of North Africa had on Delacroix’s imagination.

These two figures, who are alone in the Houston painting, reappear in the larger, horizontal composition of the Louvre painting along with two more women of the harem.

Despite having spent only four days in Algiers, during his brief stay there Delacroix created numerous sketches and watercolors, noting details of the interiors, the names of the people he painted, and descriptions of clothing. Upon returning to Paris, he used these sketches to inform the oil paintings he produced in his studio, including the Women of Algiers.

The third painting of this scene — the one in Montpellier, France — was created between 1847 and 1849. The composition of the figures is the same as the Louvre version, but the black slave is now lifting away the curtain to reveal the three seated women to the viewer.

The figures here are smaller, pulled from the dimness by a shaft of light entering from behind the drape, and the handmaid is virtually lost in shadow. The melody of gold, burnt umber, and red tones blending together creates a hazy, dreamlike setting. The woman on the left wears a more deepy-plunging neckline, revealing her décolletage, and she gazes provocatively at the viewer. This version of the theme objectifies and eroticizes the Algerian women to a greater extent than the original two.

Both the Louvre and Montpellier paintings were famously admired by Van Gogh and Gauguin, and by Picasso who, in homage, produced his extensive 1954–55 series of 15 paintings and numerous drawings and prints of the same title .

114 cm × 146.4 cm (45 in × 57.6 in) Private collection

Delacroix’s first Women of Algiers in Their Apartment (1833–34) will go on view on October 3 at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston.

Hmmmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a little trip?

Museum of Fine Arts Houston

1001 Bissonnet, Houston, TX

713-639-7300

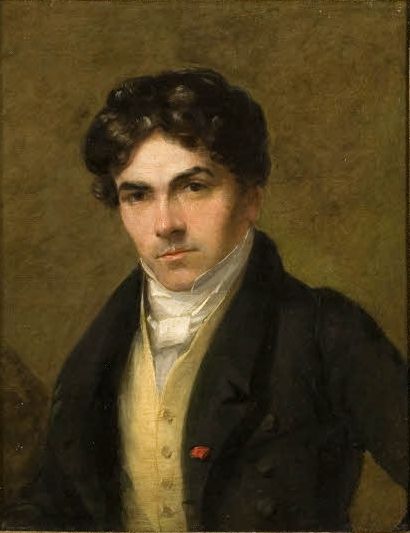

Featured headline image: Portrait of Eugène Delacroix, c. 1825 by Thomas Fielding, Musée Delacroix , Paris, France

Art Things Considered is an art travel blog for art geeks, by ArtGeek.art — the search engine for finding more than 1300 art museums, historic houses and artist studios, and gardens across the US.

My partner and I stumbled over here coming from a different web address and thought I

may as well check things out. I like what I see so now i am following you.

Look forward to exploring your web page again.

we’re happy to hear that you like our Art Things Considered blog and the ArtGeek.art website. You must be fellow art geeks!

I read this article fully about the difference of latest and earlier technologies, it’s a remarkable article.

Dear artgeek.io administrator, Your posts are always thought-provoking and inspiring.

To the artgeek.io administrator, Keep sharing your knowledge!

Dear artgeek.io owner, Thanks for the post!

To the artgeek.io admin, You always provide great examples and real-world applications.

Hello artgeek.io owner, Thanks for the great post!

Dear artgeek.io owner, Thanks for the well-organized and comprehensive post!

Hi artgeek.io owner, Keep it up!

Dear artgeek.io administrator, Thanks for sharing your thoughts!

Hello artgeek.io administrator, Keep up the good work!

Hi artgeek.io owner, Thanks for the well-researched post!

To the artgeek.io owner, Keep the good content coming!

Dear artgeek.io owner, Thanks for the post!

Hello artgeek.io admin, Thanks for the informative and well-written post!

Hi artgeek.io owner, Thanks for the well-structured and well-presented post!

Dear artgeek.io webmaster, You always provide useful information.

Hi artgeek.io admin, Thanks for the informative post!