Icons are not intended to be viewed in Western art-critical terms. Iconographers create them as sacred objects of Orthodox Christian devotion. Nonetheless, these stylized ritual artifacts can be appreciated for their aesthetic qualities as well as their spiritual essence.

The separation of the Western and Eastern Mediterranean churches began very early in the history of Christianity as a result of theology, politics, and culture. Over the centuries, West and East — Pope and Patriarch — became increasingly isolated from each other because of language differences (Latin versus Greek), and, more importantly, oppositional doctrinal beliefs. The Great Schism of 1054 formally split medieval Christianity into two branches: Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism.

One significant difference in theology is made visible by depictions of Christ in the art of the two Churches. The Latin Church, while believing in the divinity of Christ, emphasizes His humanity. Conversely, the Greek Church, while fully believing in the humanity of Christ, focuses on the mystery of His divinity.

Icons – along with chanting and choral singing, incense, vestments and the ritual motions of the Orthodox priest and acolytes — are integral aspects of the liturgical event, together revealing and celebrating apostolic meaning.

The word “icon” simply means “image” in Greek (eikṓn). Given the Greek foundations of the Eastern Church, the term “icon” has come to refer to the sacred images that are venerated by Orthodox believers.

Icons act as a conduit between the worshiper and the holy personage depicted. Icons are revered because their inherent sanctity sets them apart from other material objects. There is no distinction between the spiritual and the aesthetic nature of an icon, as it imparts God’s presence through the senses: the experience of glory and beauty.

Enameled frame with silver loop at top for a neck chain.

“The honor which is paid to the image passes on to that which the image represents, and he who does worship to the image does worship to the person represented in it.”

The Council of Nicaea (787 A.D.)

Russia, Rostov School

Museum of Russian Icons

In that context, then, icons are not intended to be viewed in Western art-critical terms.

If your exposure has been primarily to Western art, it can be difficult to fully appreciate the artistry of icons. They can seem flat, the figures distorted. Stylized images of the Virgin and Child seem repetitive, in a “you’ve seen one, you’ve seen ‘em all” sort of way.

Inevitably, though, the intrinsic grace of icons often does appeal to non-Orthodox devotees of beauty. This is not unprecedented, by any means. It’s true of many cultures whose unique ritual objects are appreciated by others for their aesthetic rather than their spiritual essence. Think of the African tribal masks, for example, and Native American ceremonial objects that are prized in the collections of many museums.

While there has been change and development over the centuries, since the Byzantine Iconoclasm of 726–842 icons have had a far greater continuity of style and subject than have images of the Western church.

Beginning around 600 A.D. the Roman Catholic Church began to use imagery as a “bible of the poor,” from which those who could not read could nonetheless learn. Gradually the Western tradition allowed artists greater flexibility in the representation of figures, settings, and narrative. Eastern icons can also depict narrative Biblical scenes, but they are less common. Icons primarily represent “portraits” featuring one or two main figures.

As the Byzantine Church expanded through Moravia and into the Balkans and Russia in the 9th century, styles evolved as indigenous art traditions were absorbed into the production of icons. But within those various local schools, there was little room for artistic license.

Virtually everything in the image symbolizes something. Angels — and often John the Baptist — have wings because they are messengers. Figures have consistent facial appearance, they hold personal identifying attributes, and they are placed in a few conventional poses.

British Museum, London

13th century; Saint Catherine’s Monastery Mount Sinai, Egypt

Color speaks. Gold represents the radiance of Heaven; white is the revealed Light of God, representing the resurrection and transfiguration of Christ. Red is divine life, while blue is the color of human life. For example, an icon in which Jesus wears a red garment beneath a blue outer garment represents God become Man.

Iviron Monastery, Mount Athos

Letters are symbolic, too. Most icons incorporate some calligraphic text naming the person or event depicted. Even this is often presented in a stylized manner, and in Greek.

Orthodox believers are familiar with these conventions and are thus equipped to receive the devotional message.

The Virgin Mary and Christ are the two holy figures most frequently depicted, each with stylistic prescriptions.

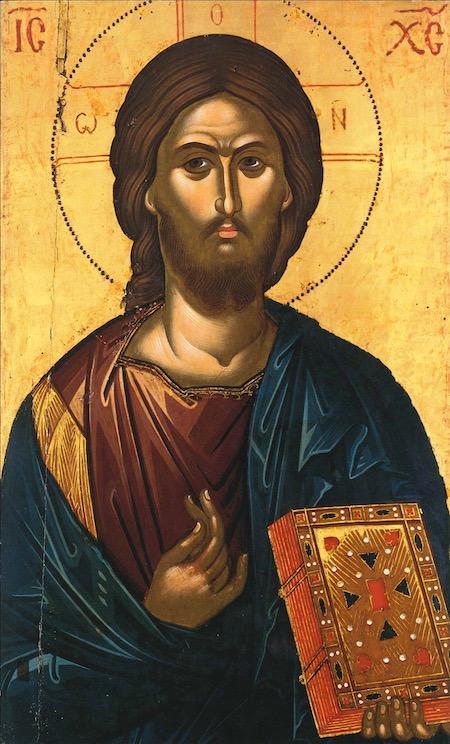

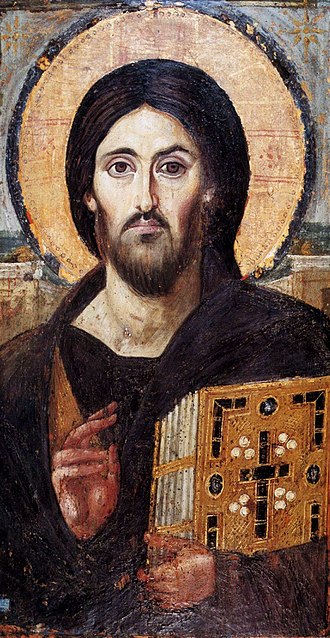

The icon of Christ Pantocrator is one of the most common religious images of Orthodox Christianity. The term Christ Pantocrator — derived from one of many names of God in Judaism – is most commonly translated as ” All-powerful.” The traditional iconography shows a God-like Christ in frontal half-length, holding a closed book of Gospels in the left hand while the right hand is raised in blessing. The face is often painted with a rather melancholy or stern aspect.

In Deisis depictions the Virgin and John the Baptist appeal to Christ on behalf of humanity for mercy at the time of judgment.

Christ is bearded, his brown hair parted in the middle, his head encircled by a halo. It is often a cruciform halo, inscribed with the letters Ο Ω Ν, meaning “He Who Is”.

The icon is usually shown against a gold background. Often a monogram of Jesus’ name is written on each side of the halo, as IC and XC. This Christogram is made up of the first and last letters of ‘Jesus’ and ‘Christ’ in Greek.

A variant of the Pantocrator icon is Christ the Teacher, showing an open book in the left hand.

The image above shows clearly the iconic gesture of blessing. In what amounts to an ancient form of sign language, the position of the fingers configures the Christogram letters IC XC — so the hand that blesses speaks the Name of Jesus, “the Name above every name.”

These conventions evolved over centuries, but the way was not always smooth. Very early on, for example, there was controversy over whether Jesus should be represented in “Semitic” form, eg, with short and wavy hair, or – in the way the god Zeus had always been depicted — shown bearded with longer hair parted in the middle. Asserting that short kinky hair was “more authentic,” Theodorus Lector told of a pagan who painted an image of Jesus using the “Zeus” form instead of the “Semitic” form — and then his hands withered by way of punishment.

Despite this apocryphal warning, it seems the center-part prevailed.

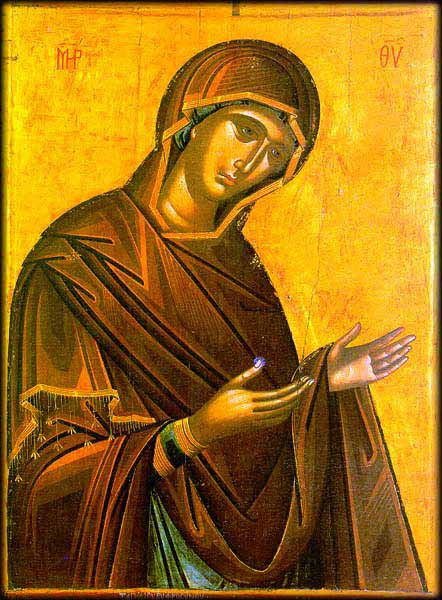

The Virgin Mary is referred to as Theotokos, which is translated in numerous ways, including Mother of God, God-bearer, and Birth-giver to God. Theologically, icons of the Theotokos represent the first human being who realized the goal of the Incarnation: the deification of man.

Iconographers strive to impart gentleness, dignity and grandeur to Theotokos. She is sometimes shown grieving, but always radiant with spiritual strength and wisdom.

She is shown with her head covered with a veil which falls to her shoulders, according to the traditional mode of Jewish women. This head covering is usually colored red to show her suffering and her acquired holiness, while under the veil, her clothing is blue, symbolizing her humanity — or vice versa. Often there is just the merest peek of the contrasting-color sleeve at the wrist to convey the message.

There are three golden stars, one on the forehead and one on each shoulder of the Most Holy Theotokos. These stars are symbols of her virginity before, during, and after the Nativity of Christ, and they also point to the Holy Trinity. Sometimes the third star is masked by the figure of the Christ Child, the second person of the Holy Trinity.

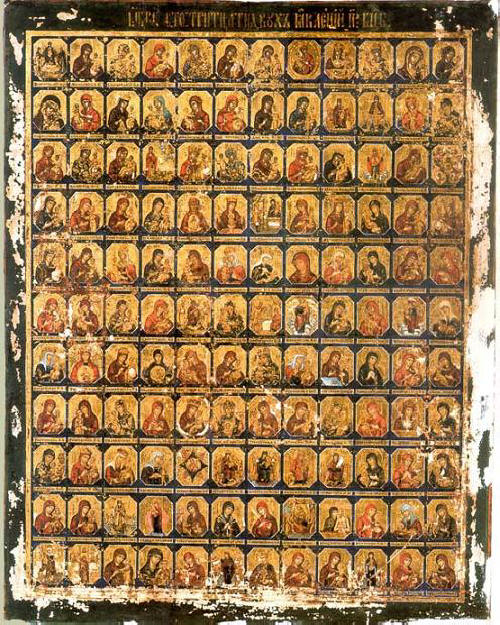

There are five main types of the Theotokos in Orthodox iconography.

The Museum of Russian Icons. Clinton MA

One of the most prevalent types, is The Guide, or Hodegetria, in which the Theotokos holds Christ and, gesturing toward Him, points to Him as the source of salvation for humankind.

In another type, known as Tender Mercy, or Eleusa, the Theotokos holds her Son as he touches his cheek to hers and embraces her with an arm around her neck. This Theotokos represents the Church of Christ, projecting the fullness of love between God and humanity, a love that is achieved within the Church, the Mother. Some of these icons project a sublime tenderness.

In the All Merciful / Panakranta type, Theotokos is enthroned, holding her Son on her lap, both facing the viewer. The throne symbolizes her royal glory, she alone is perfect among those born on earth and, according to the Council of Chalcedon in 451 a.d., she presides with Christ over the destiny of the world.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

by Euphrosynos, 1542

As the Intercessor, or Agiosortissa, Theotokos is shown alone, turned to the side with her hands held out in supplication, usually addressing a separate icon of Christ. She is often shown in full height, sometimes carrying a scroll.

In the fifth type, called Praying, Oranta or Panagia, Theotokos is usually shown full-length, facing the viewer with arms in orans (open prayer) position. The image of Christ appears within a circle that represents her womb.

“Those who see in a secular way say that it [Western art] progressed, but those who see in a religious way say that it declined.”

Photios Kontoglou (1896-1965)

While icons are not intended as art in the usual sense, those of us who do not practice Orthodox Christianity can better appreciate these sacred images by knowing something about the underlying iconography and typologies. These deeply symbolic images can be more accessible to us if we lay aside expectations of artistic originality and realism.

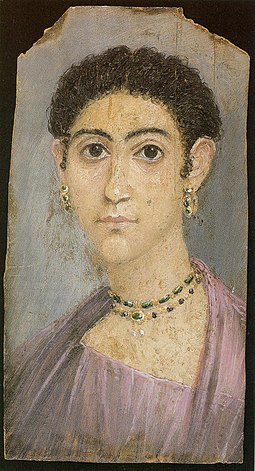

c. 100 AD

Hawara, Egypt

British Museum

In many ways, icons reveal the world into which Christianity was born – an intersection of Greek and Roman culture, Judaism and the religion of Egypt. The earliest icons reflect an evolution out of Classical and Egyptian art.

Note the similar stylistic convention in this mummy portrait of a young woman, painted in Egypt at the end of the 1st century AD.

“Where is the perspective?” you may ask. “Why is there no vanishing point to provide the illusion of depth on the flat plane?”

Consider that perhaps the vanishing point is to be found in the heart of the viewer — an “inverse perspective” by which the space between the icon and the viewer is charged with a Divine Presence.

Every icon is an interaction between heaven and earth.

St. Catherine’s Monastery at Sinai has remained intact since it was built by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian in the early 6th century, and it can be said to have preserved the distinctive qualities of its Greek and Roman heritage. By virtue of an isolated location and dry climate, St. Catherine’s holds more than half of all the Byzantine icons that survive in the world today.

The image at the top of this article, the Christ Pantocrator of St. Catherine’s Monastery at Sinai, is one of the oldest surviving Eastern religious icons, dating from the 6th century.

But there’s no need to travel to far-away lands to see sacred Orthodox Christian icons. Many US museums — like New York’s Metropolitan Museum and the National Gallery in Washington DC — hold at least a few icons in their collections. The Museum of Russian Art in Minneapolis exhibits icons, among other art forms. For the most in-depth exposure to be found in the US, the Museum of Russian Icons in Clinton, MA holds the largest collection of Russian icons outside Russia.

Hmmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a little trip?

This is very helpful in understanding icons. Thanks!