Not unlike Grandma’s curio cabinet, a 16th- and 17th-century ‘cabinet of curiosity” was filled with a collector’s treasures. Although a small collection might have been laid out in a drawer, or arrayed on shelves, the term cabinet originally was defined as a room rather than a piece of furniture (think water closet and the Italian equivalent, gabinetto).

It became popular among the European monied classes — from royalty to merchants — to collect objects that said something about the world and its history — the exotic, the esoteric, the beautiful as well as, occasionally, the repulsive. They also were intended to say something about the collector’s intellect, erudition, wealth, and taste.

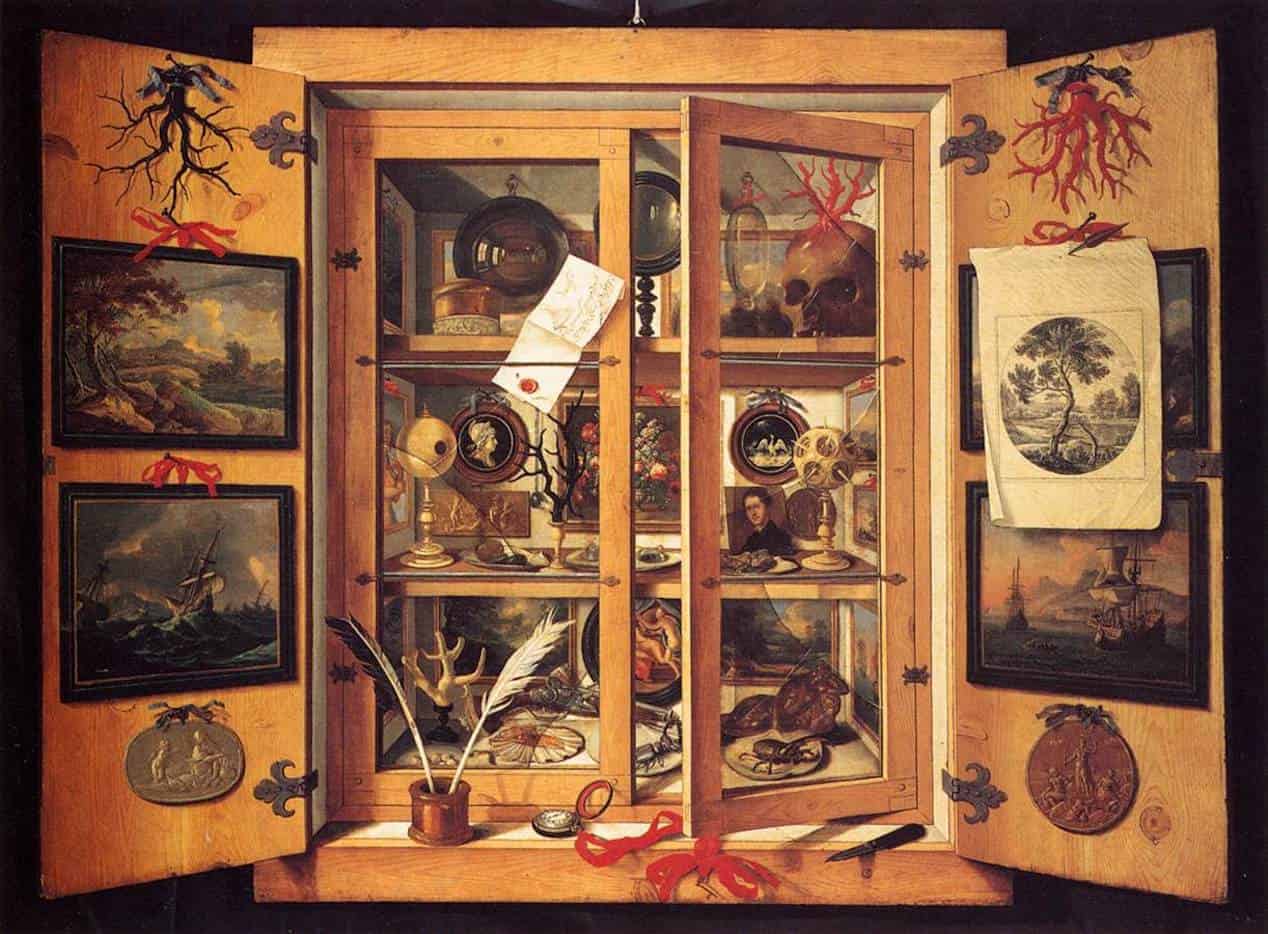

Fans Francken II, Kunst- und Raritätenkammer

(Chamber of Art and Curiosities), 1636

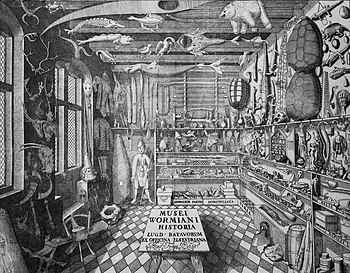

“Musei Wormiani Historia” frontispiece, depicting Wormius’ cabinet of curiosities, 1655

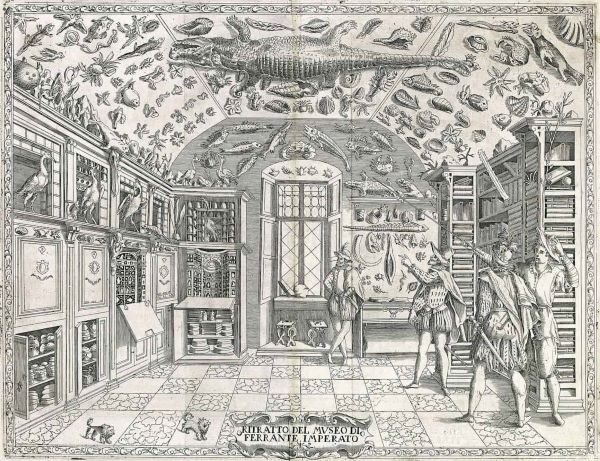

Fueled by increasingly global trade and exploration, cabinets of curiosity commonly featured antiques, objects of natural history (such as taxidermized animals, dried insects, shells, skeletons, shells, herbarium, fossils) as well as works of art. Also known as wundercammer, they were constructions of the collector’s personal version of the world.

Ferrante Imperato, Dell’Historia Naturale (Naples, 1599)

Although the distinction between art objects and natural objects was quite fluid, these collections were often organized into categories. One categorizing system that was detailed in 1565, called for, in Latin: Naturalia (created by the earth and drawn from nature), Mirabilia (unusual natural phenomena), Artificialia (made by man),

Ethnographica (from the wider world), Scientifica (items that expanded understanding of the universe) and Artefacta (relating to history).

Another, perhaps simpler, system proposed: Artificialia; Naturalia; Exotica (exotic plants and animals); and Scientifica (scientific instruments).

By the early decades of the 18th century, curiosities and wondrous specimens began to lose their influence. A new scientific emphasis on patterns and systems within nature caused anomalies and rarities to be regarded as potentially misleading objects of study. By the 18th century, specialized disciplines of study were emerging (e.g. art history, archeology, geography, ethnology), and collections became less exotic and more oriented toward study.

The most widely known and best documented cabinets of rulers, aristocrats, merchants and early practitioners of science held significant collections that were precursors to today’s museums.

And, speaking of museums …

Just after I’d made my way into the European Art Galleries at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, I caught a peripheral glimpse through an open doorway of something unexpected and truly wunderbar. “STOP” I almost shouted to my companion, who was ahead of me. “Come and look at this!”

Cabinet of Curiosities, installation view

MFAH has recreated a cabinet of curiosities, and to enter is like stepping into a treasure chest!

Installation view

Installation view

Treasures, from a van Dyck, a Brueghel, a Chardin, a Fragonard and a Rubens (attrib.) to small bronze sculptures, Egyptian amulets, sundials, a pocket globe, skeletons and fossils, small ceramic and glass objects. Treasures, stacked salon-style and displayed in gleaming glass vitrines.

In the early days of wunderkcammern, there was a certain amount of truth-stretching and spoofery, unintentional and otherwise. For example, it was not uncommon for a Narwahl tusk to be touted as a unicorn horn. When the curator of this MFAH cabinet of wonders, James Clifton, was asked if he was pulling any legs here, he admitted that one of the books, a Royal Society catalog from 1681, was opened to a page titled “Skin on ye Buttock of a Rhinoceros.” Another book, titled “The Microscope Made Easy,” Clifton described as “Microscopes for Dummies in 1744.” He also shared that the natural objects on view—shells, mostly—came from Ebay!

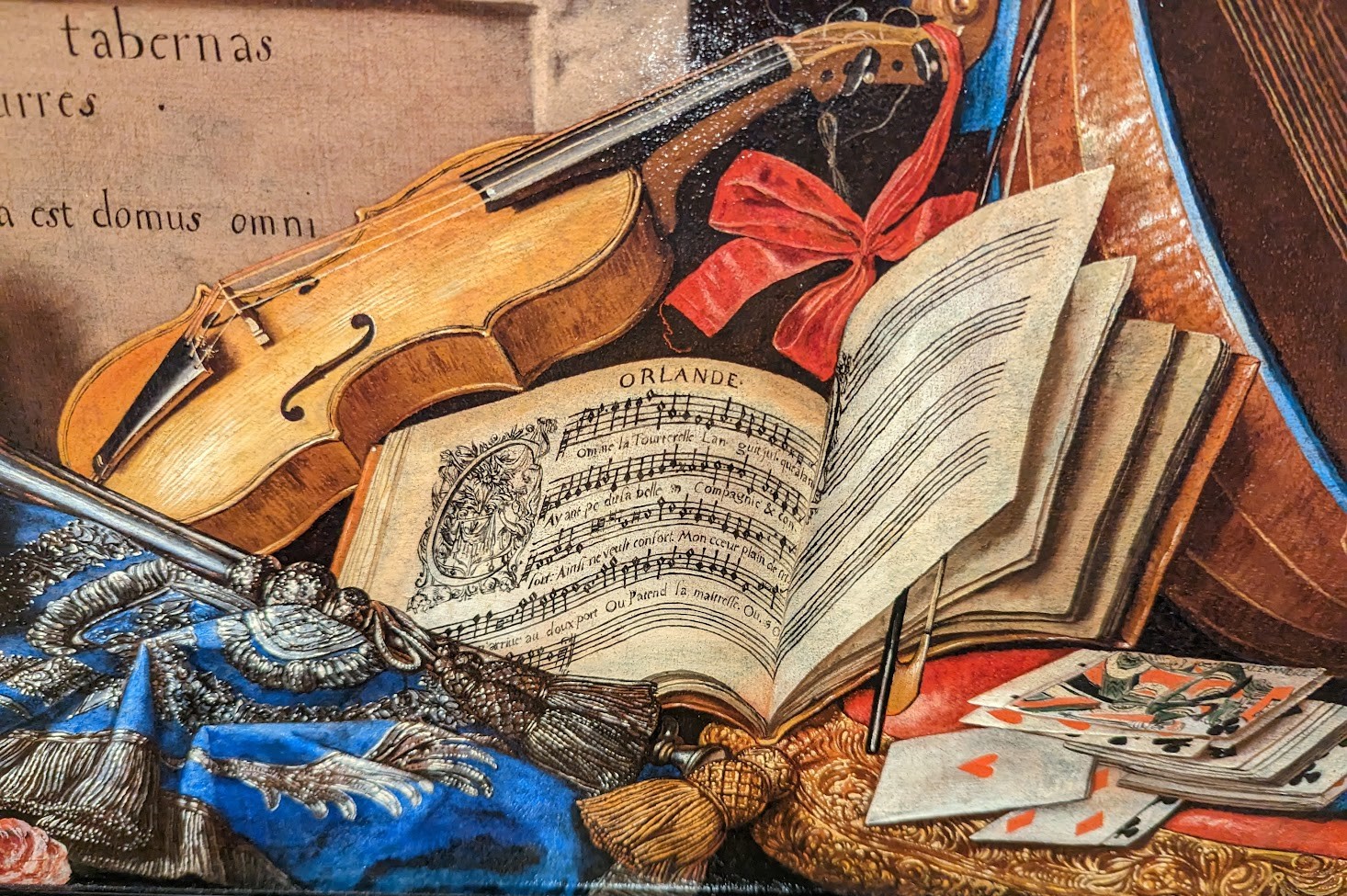

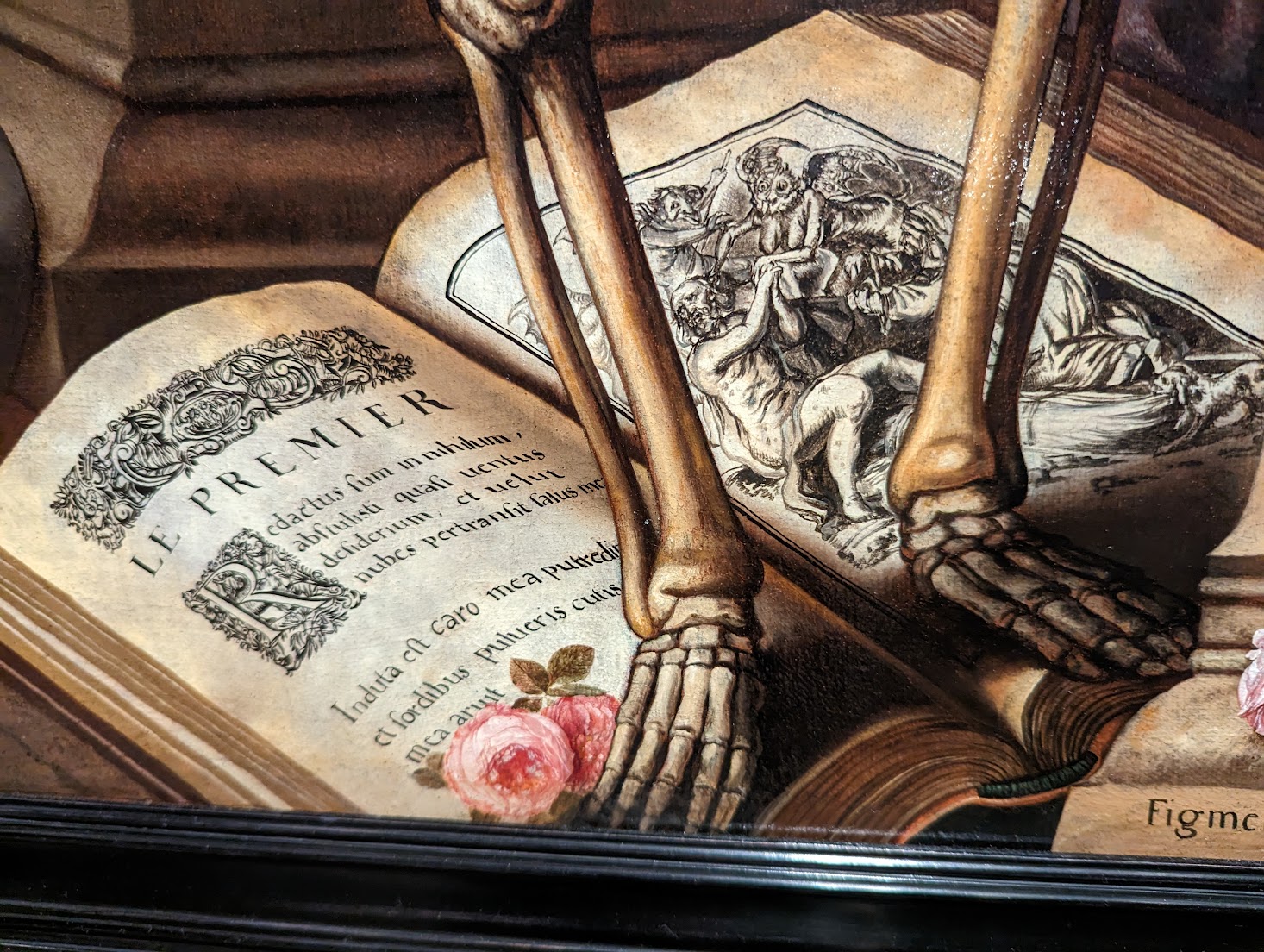

One favorite piece for me was Christian Luycks’ c. 1653 A Vanitas Still Life with Musical Instruments, Sheet Music, Books, a Skeleton, Skulls and Armor, bursting with story-telling details…

Christian Luycks, A Vanitas Still Life, c. 1653

Luycks, A Vanitas Still Life, detail

Luycks, A Vanitas Still Life, detail

Some time ago, Clifton removed the descriptive labels from the exhibit and rehung the paintings to more accurately resemble the cabinet of a gentleman collector of the 18th century. The labels have been replaced with a stack of take-away menus which illustrate and describe the objects, numbered wall by wall.

A real surprise came the following day, when we came across another cabinet of curiosities in Houston, at the Menil Collection!

In 1999, the Menil Collection opened an installation called Witnesses to a Surrealist Vision, which remains on view today. True to the cabinet of curiosities concept, it’s a collection of exotic, mostly anthropological objects that was inspired by the collections of Surrealist artists including, apparently, some pieces that actually belonged to André Breton. (A writer and poet, Breton is considered to have been a founder, leader, and principal theorist of Surrealism.)

Witnesses to a Surrealist Vision, installation view

Image courtesy of the Menil Collection

“Filled with paintings, sculptures, masks, musical instruments, curios and other things, the gallery emulates the interiors of Surrealists’ studios and homes as well as the Wunderkammer, or cabinet of curiosities, in early natural history museums. During the first half of the 20th century, Surrealist artists and authors were avid purveyors of the “arts premiers,” arts of Indigenous people […]

“A general lack of concern for an item’s original cultural use or history allowed the Surrealists to expropriate these objects to explore their interests in accessing the power of the unconscious, the legitimacy of dreams, and the universal significance of mythology,” according to the Menil Collection website.

Installation view

Installation view

This delight-filled, culturally heterogeneous display of more than 150 objects was put together under the direction of anthropologist Edmund Carpenter (1922–2011). Ritual and everyday objects, primarily from the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Islands and the Americas, are shown side-by-side with 19th-century European anamorphoscopes, astrolabes, and other devices that offer alternative ways to perceive and understand reality.

Installation view

Perhaps the most bizarre item in the Menil wunderkammer is the extraordinary spiked body suit that stands proud, center-stage. Sometimes referred to as a Siberian bear-hunting suit, it consists of leather pants and shirt, and a spiked iron helmet. The suit is covered top to bottom with one-inch iron nails spaced roughly ¾ inch apart. In her 2014 Masters thesis, Kristen Strange of Arizona State University wrote: “While it is now thought to have originated in 18th- or 19th-century Germany or Switzerland, this costume presumably represents a folk figure seen in the Vogel Gryff Festival in Basel, but it has also been considered a bear hunting costume.“ The Menil description says, ‘Wildman’ costume, 18th or 19th century, Germany or Switzerland. Two-piece leather hunting suit with wood spikes and iron chain.“

‘Wildman’ costume

Asmat, Body Mask

Courtesy of Menil Collection

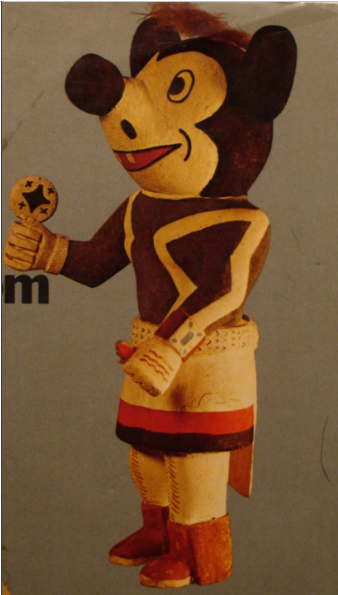

Hopi, Mickey Mouse Kachina

Giuseppe Arcimboldi (attrib.), Winter (L’inverno)

Courtesy of Menil Collection

Three favorites, besides the extraordinary spiked body suit, were an Asmat Body Mask from Papua, New Guinea, a 1950 Mickey Mouse kachina from the Hopi in Arizona, and Giuseppe Arcimboldi’s 16th-century Winter (L’inverno) (attrib.).

Morian Cabinet of Curiosities at the Houston Museum of Natural Science

It was only after I sat down to write this article that I discovered that there is yet another wunderkammer in Houston: a permanent display at the Museum of Natural Science, called the Morian Cabinet of Curiosities. And, I’m told, the gift shop sells plenty of items for those who are inspired to head home and set up their own wonder cabinet.

Of course it makes sense that a natural history museum would want to tip its hat to historical collections of natural objects, which reflected man’s desire to find his place within the larger context of nature and the world. Many of these private collections were ultimately institutionalized and became the first public museums, and they might have looked very much like this — although not as well lit!

Installation view

Installation view

All this makes me wish I had a child of an age to start a Cabinet of Curiosities project. It would make gift giving fun and easy for the next few years!

Hmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a little trip …

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

1001 Bissonnet, Houston, TX

713-639-7300

Read about our visit to the MFAH in our Art Things Considered blog.

Menil Collection

1533 Sul Ross St., Houston, TX

713-525-9400

Houston Museum of Natural Science

5555 Hermann Park Dr., Houston, TX

713-639-4629

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the only search engine that makes it easy to discover almost 1700 art museums, historic houses & artist studios, and sculpture & botanical gardens across the US.

Just go to ArtGeek.art and enter the name of a city or state to see a complete interactive catalog of museums in the area. All in one place: descriptions, locations and links.

Use ArtGeek to plan trips and to discover hidden gem museums wherever you are or wherever you go in the US. It’s free, it’s easy to use, and it’s fun!

© Arts Advantage Publishing, 2023