This is the first major exhibition since 1925 to explore Sargent’s expressive drawings in charcoal, illuminating the magnitude of his abilities as a portrait draftsman. The drawings in the John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal exhibition at the Morgan Library and Museum represent an important yet often overlooked part of Sargent’s practice.

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) is widely known for his powerful figural paintings, especially his majestic portraits of society ladies. But the arduous sittings – a dozen or more – that were required to complete a single portrait took a toll on both sitter and artist. For the most part, in 1907 he stopped painting portraits (or “paughtraits,” as he called them). “I abhor and abjure them and hope never to do another especially of the Upper Classe,” he wrote in a letter to a friend.

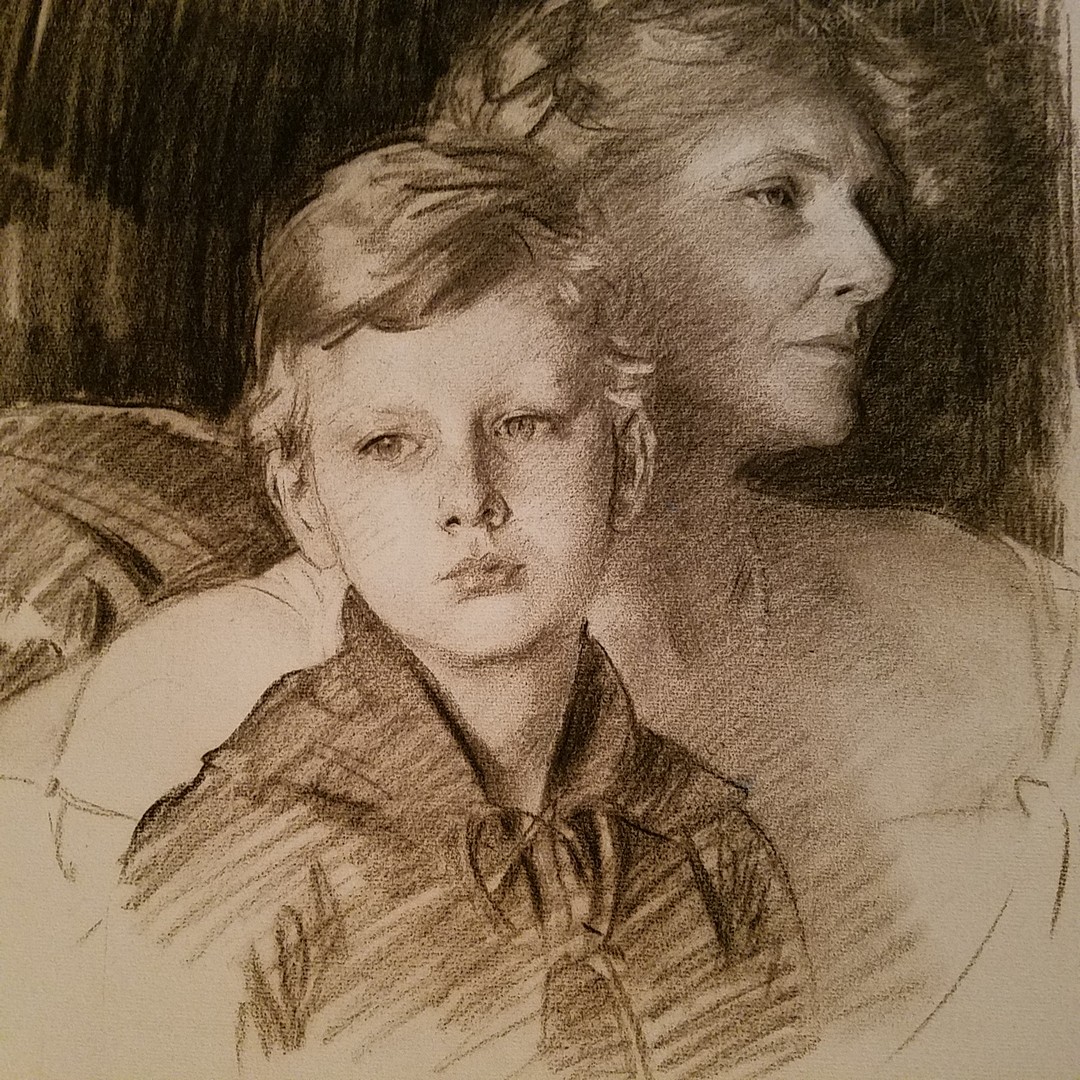

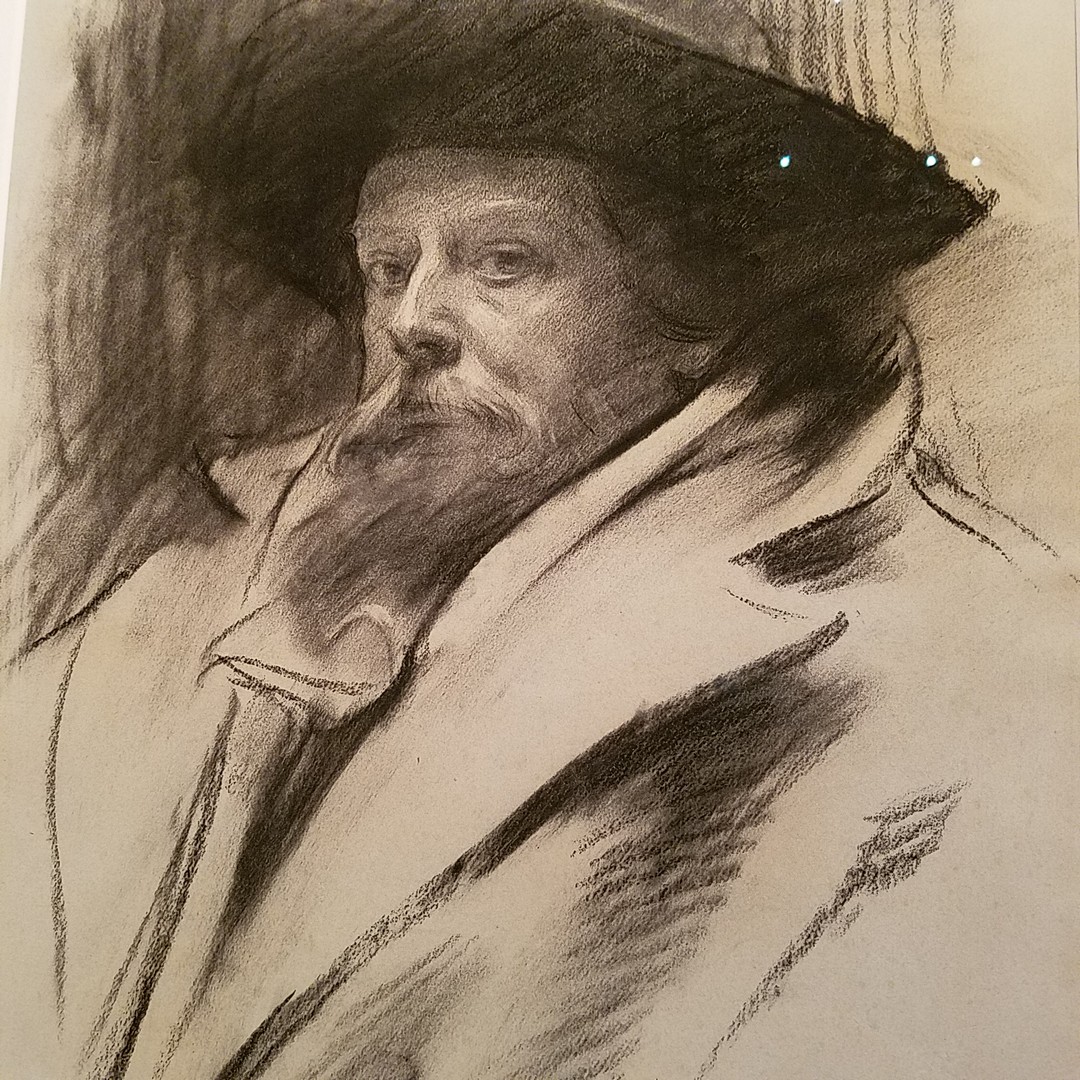

From then on, if he could satisfy a portrait commission with a charcoal drawing, he was game. He could complete a portrait in a single sitting of two or three hours, in which time he produced pictures projecting a sense of immediacy and psychological insight – the essence of his subject captured.

Mrs. Greene was an art collector and philanthropist

Sargent was the leading portrait artist of his time. Born in Florence to expat American parents, he was equally at home in Europe and the US, and made a name for himself on both sides of the Atlantic.

The introductory wall-text for the exhibit makes the point that “The people portrayed by Sargent shaped not only his life but also the social and cultural fabric of the United States and Great Britain in the early 20th century.” Moving through the exhibition, one does get a strong feeling of Sargent’s social position, that he counted so many of these illustrious figures among his circle of friends.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston MA

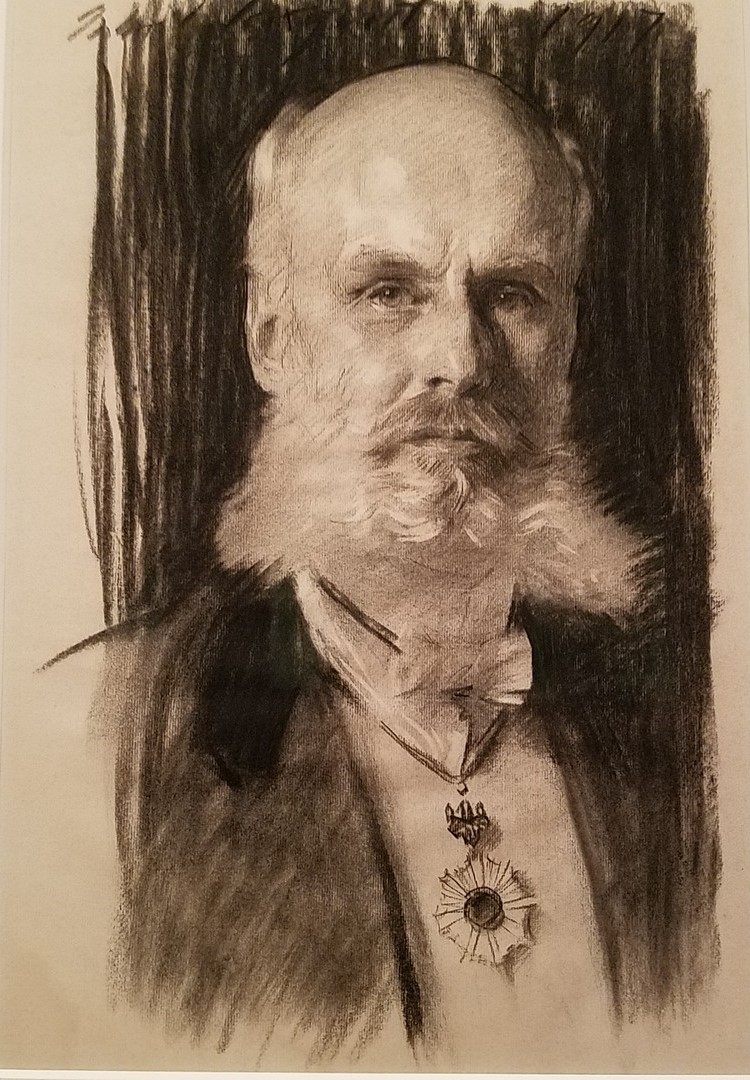

Bigelow left 40,000 works of Japanese art to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

As was the case with his oil portraits, Sargent’s charcoal portrait subjects came from a wide range of circumstances, from British aristocrats to newly-wealthy American businessmen, from high-society ladies to suffragettes. He travelled back and forth between the US and Europe, as did the trans-Atlantic elite among his sitters. He produced more than 750 charcoal portraits of public figures, patrons and friends.

National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

Sargent painted and drew her numerous times, telling Arthur Rubenstein, “I have never known anyone with the unfailing uncanny taste of this woman.”

One sitter described his work process this way: “He was a very quick worker [and] put the sitter on a chair close to the easel then walked away to the end of the room — & dashed back & put in 2 or 3 masterly strokes with charcoal – then back again — & so on – till the sketch was finished in about 3 hours.”

In his late teens, Sargent studied drawing at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where drawing was emphasized as essential to an artist’s development. At the time, advancements in charcoal manufacture produced a greater range of colors, densities and shades, which boosted the popularity of the medium. Sargent drew throughout his life, using various media, but his commitment to charcoal greatly increased in the later decades of his career.

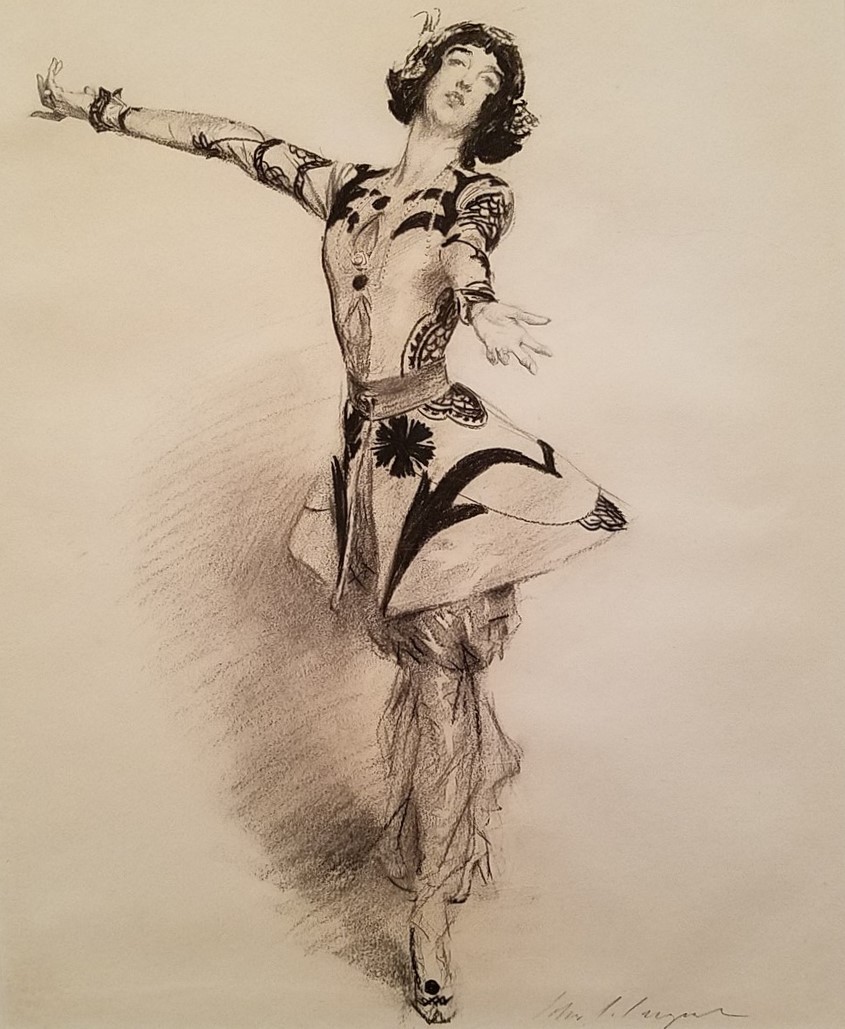

The exhibition is organized into groupings of sitters, according to their profession (musicians, the theater, writers & thinkers), their role in society, or their relationship with Sargent.

Artists, Patrons, Friends considers the ways Sargent’s professional and personal relationships overlapped, and demonstrates how the familiarity of friendship between himself and the sitter presented him with opportunities for artistic experimentation.

Richmond was a friend and fellow artist.

One wonders, was he drawing Sargent while Sargent was drawing him?

Although most of the people depicted would have been widely recognized in their day, awareness of their status and contributions has diminished over time. Thus, one of the delights of the exhibition is the biographic information provided in text adjacent to each portrait, revealing how the individual fit into the fabric of early 20th-century Anglo-American society.

For example, we’re told that Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney was never comfortable with her position as an heiress to a vast fortune, that she trained as a sculptress and became widely respected for her monumental sculptures, that she was a generous patron of the arts, and that it was she who founded the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1930 with a collection of 500 works by 20th century American artists. Would you have guessed all that by looking at this portrait?

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

The Musicians section conveys that Sargent was an accomplished pianist and avid concertgoer. Apparently, while working on a portrait of a composer, singer, or musician, he often would break off drawing and dash to the piano to play a few bars.

He was “an admirable musician … He was in music as in all things ‘frightfully intelligent’.” Charles Loeffler, violinist and composer

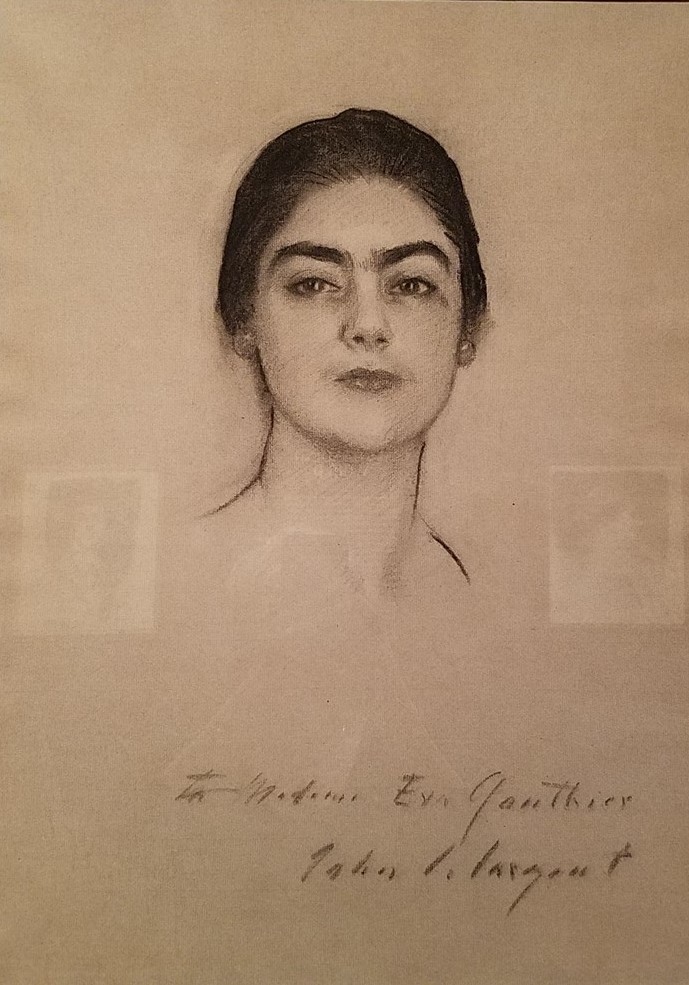

Text adjacent to the straighforward portrait of Canadian-born Eva Gautier refers to her as the “High Priestess of Modern Song.” An opera singer, she lived in Java for three years and developed a repertoire of Javanese and Malayan music. Back in New York, she sang these dissonant melodies in concert, often in costume, gaining the notice of contemporary composers including Eric Satie, Maurice Ravel, and Igor Stravinsky.

The New York Public Library, New York, NY

The section of the exhibition labelled A Changing World considers the extraordinary social shifts and progressive political reforms of the early decades of the 20th century. These portraits depict men and women whose lifestyle traditions were inexorably affected by this unprecedented social upheaval.

John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal exhibition

Marguerite Severine Philippine Decazes de Glucksberg – called Daisy – became the Paris editor for Harper’s Bazaar in 1933. Hailed as “the fashion leader of Paris,” she was the daughter of a Duke and an heiress to the Singer sewing machine fortune. Embracing the avante-garde, she believed that “good fashion is daring fashion, not a polite one.”

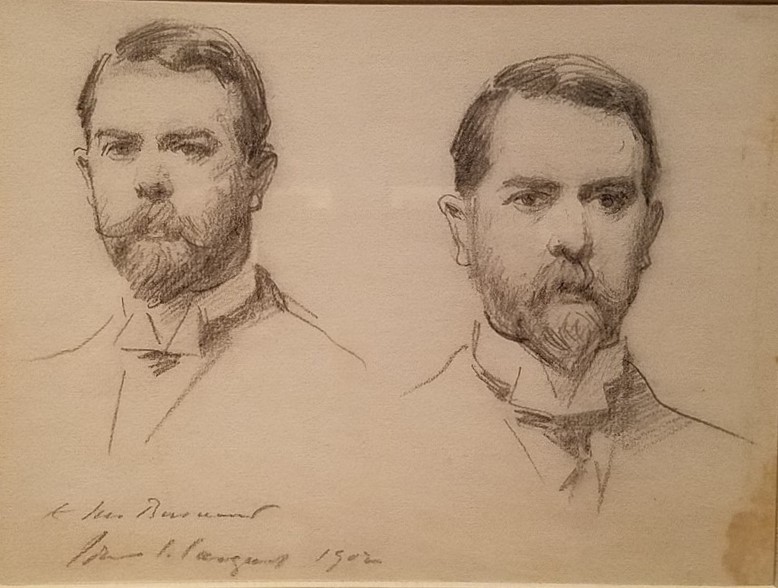

Private Collection, Columbus, GA

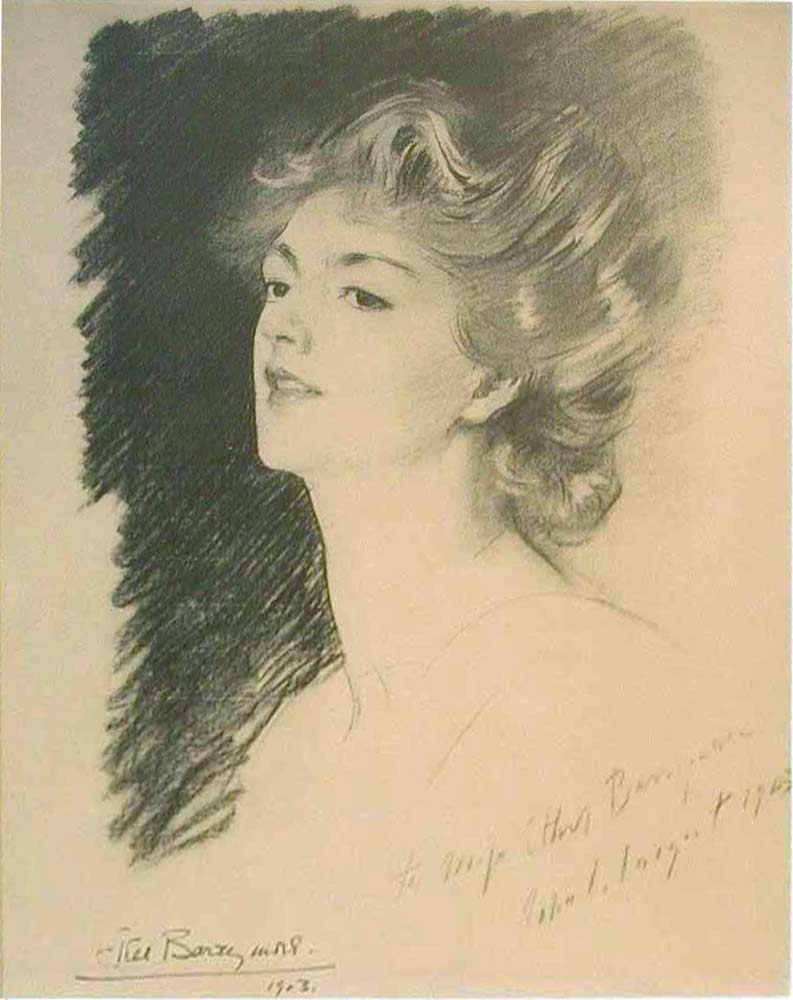

Actors and actresses inspired Sargent. In 1903 he wrote to Ethel Barrymore asking, “Would it be possible for you to give me an hour or maybe two? I would like to do a drawing of you and I would be so honoured to present you with the drawing afterward.”

Private collection

Although Sargent produced more than 1300 painted and drawn portraits of others, he seldom represented himself, claiming he was “bored” with the process of making self-portraits. The featured image at the top of this article is one of the few. Double Self-Portrait was drawn in 1902 using graphite rather than charcoal. In this drawing, which is held in a private collection in Columbus, GA, he shows himself wearing the wing collar and tie that he favored.

John Singer Sargent died in London sometime during the night of April 14-15, 1925. He was mourned and remembered with memorial exhibitions on both sides of the Atlantic. The Royal Academy of Arts in London mounted an exhibition of more than 65 charcoal portraits of Sargent’s friends and patrons.

John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal is the first time since then that these captivating drawings have been featured in a major exhibition, and some of the works displayed then can be seen in this engaging show.

The Royal Academy of Arts, London.

Hmmm …. maybe it’s time to plan a little trip?

The Morgan Library & Museum (on through January 12, 2020)

225 Madison Avenue at E. 36th St, New York City, NY

212-685-0008

National Portrait Gallery (February 28 – May 31, 2020

8th and F Sts., NW, Washington, DC

202-633-8300

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the search engine that makes it easy to discover more than 1300 art museums, historic houses and artist studios, and gardens across the US.

Your posts are interesting.

The https://blog.artgeek.io it’s one of the best sites I’ve ever seen, and

the John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal

– ArtGeek article is great.

Like!! Thank you for publishing this awesome article.

I am typically to blogging and i really appreciate your content. The article has really peaks my interest. I’m going to bookmark your website and keep checking for new information.

It’s a pity you don’t have a donate button! I’d definitely donate to this outstanding blog!

I suppose for now i’ll settle for book-marking and adding your

RSS feed to my Google account. I look forward

to brand new updates and will talk about this site with my

Facebook group.

Nice post

This is a topic which is near to my heart… Best wishes!

Where are your contact details though?