Years ago, early on in my love-affair with art, while I was still in my teens, I read a definition of tenebrism that I interpreted to mean it was just another word for chiaroscuro.

“Tenebroso (pl. tenebristi) — Name given to 17th-century artists in Naples, the Netherlands and Spain who painted in a low key, and emphasized light-shade contrasts in imitation of Caravaggio.” Encyclopedia of the Arts, Thames and Hudson, 1966

That definition is not wrong — but it is incomplete.

Tenebrism is a word surprisingly seldom used in discussions of Caravaggio and other 17th-century painters. When it is, it is typically subsumed into, or thought to simply be another word for, chiaroscuro. But it actually has a distinct characteristic that defines it.

I first came across the word years ago when I was reading about the Spanish Baroque painter, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617 – 1682). Tenebrism locked into my thinking as the word used to describe the chiarocuro technique, specifically in discussions about Spanish art .

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

I’ve just learned what it actually is …

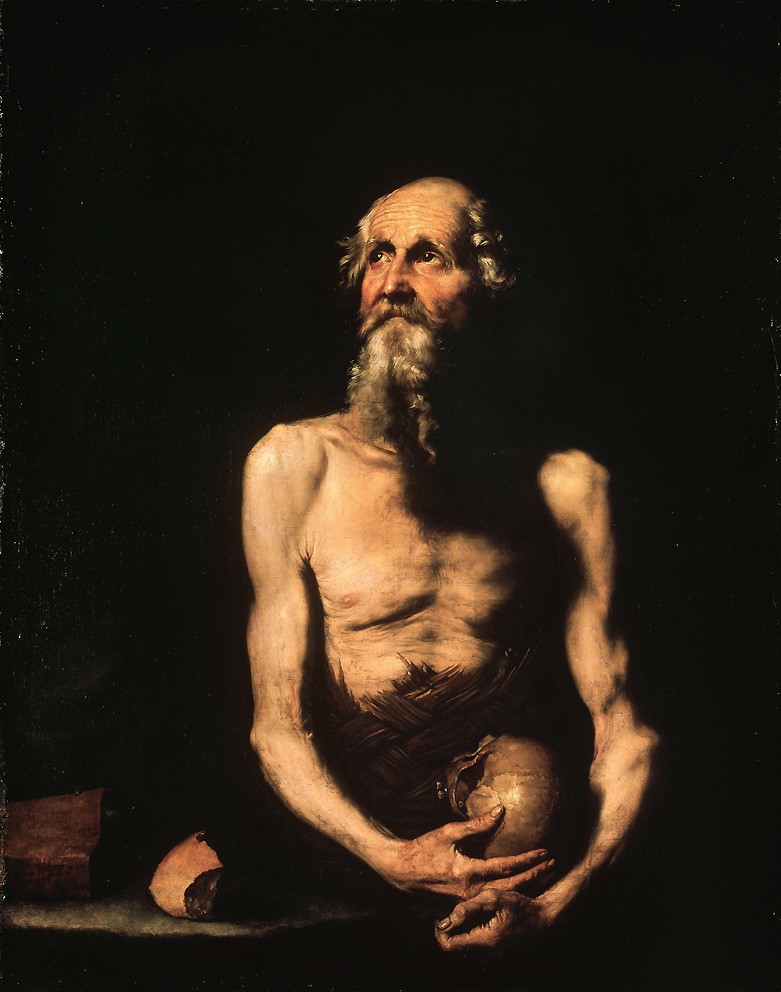

From the Italian tenebroso — meaning dark, gloomy, mysterious — tenebrism describes a compositional technique in which some areas of the painting are kept completely black, allowing other areas to be strongly illuminated, usually from a single source of light. There is no modelling involved, no attempt to include forms in the darkness which is a dominating feature of the image.

Oil on canvas, 49 in × 40 in. Galleria Borghese, Rome, Italy

The technique was developed to add dramatic impact to an image through a spotlight effect. Without the distraction of background features, the eye is concentrated on the focal essence of the image.

Sometimes referred to as “night pictures” painted in the “dark manner,” tenebrism is most often seen in Mannerist and Baroque works, including many by Caravaggio and Murillo, as well as other tenebristi in Naples, the Netherlands and Spain.

Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy

Chiaroscuro describes the distinct, but less extreme, contrast of light and shade, using shadow to create the illusion of three-dimensional form. Rather than a pure tenebrist blackness, chiaroscuro darkness holds some degree of light, making objects or figures detectible in the shadows, introducing the illusion of volume and depth to the composition.

Gerrit ter Borch (1617−1681). Finnish National Gallery

Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome, Italy

Are we dancing on the head of a pin? Some would say so, I’m sure. But considering the distinction between tenebrism and chiaroscuro can be one more perceptual tool as you look at a painting, to interpret its composition, and perhaps to infer the artist’s intent.

Feature image: Jusepe de Ribera (Játiva/Valencia 1591 – 1652 Naples), St Paul the Hermit, c. 1647, oil on canvas, 130 x 103.5 cm., Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks by ArtGeek.art — the search engine to easily find more than 1300 art museums, historic houses and artist studios, and gardens across the US.

Thank you for “illuminating” this topic! Very interesting.

Happy to hear you enjoyed the article, Margaretta!

Really appreciate this!

Glad you liked it!

What a lovely write-up, many thanks! Surprised to see I was not alone in wondering, so recently.

Very interesting distinction.thsnkyou

Great breakdown of the differences between chiaroscuro and tenebrism! I never realized how subtle yet impactful those distinctions can be in understanding artwork. The examples you provided really helped clarify things for me. Thanks for the insightful post!

Great breakdown of the differences between chiaroscuro and tenebrism! I never realized how the emotional intensity really sets them apart. Your examples were super helpful too. Looking forward to more art discussions like this!

This is such an insightful post! I love how you broke down the differences between chiaroscuro and tenebrism. It’s fascinating to see how these techniques have influenced the emotional depth of artwork throughout history. Can’t wait to explore more artists who used them!

Great post! I found the distinction between chiaroscuro and tenebrism fascinating. It’s interesting how both techniques can evoke such different emotions in art. I never realized how much of an impact lighting choices can have on the viewer’s experience. Thanks for shedding light on this topic!

I came upon the word chiaroscuro when reading “The Message” by Ta-Nehisi Coates, page 16. The author used this delicious word to describe the words of Fredrick Douglass’s treatice on slavery and freedom.”…the bright good of freedom in principle, set against the dark unknown reality—evokes the cliche’ “the devil you know.” “But Douglass’s chiaroscuro of language— “in the hazy distance” under “flickering light…half frozen,” illuminates the truth buried in the cliche’…” The word chiaroscuro, used in this literary context was an an amazing facilitator. Hence my dive into the discovery of the distinction between chiaroscuro and tenebrism! Your post was so very satisfying! Thank you

This post does a fantastic job of breaking down the differences between chiaroscuro and tenebrism! I always thought they were the same, but the examples really helped clarify how they each create mood and depth in art. Thanks for the insights!

Great breakdown of the differences between chiaroscuro and tenebrism! It’s fascinating how these techniques can drastically alter the mood of a painting. I appreciate the examples you included; they really helped clarify the concepts. Looking forward to more posts like this!

This post beautifully clarifies the distinction between chiaroscuro and tenebrism! I appreciate how you highlighted the emotional depth that tenebrism can convey compared to the subtle gradations of light in chiaroscuro. It’s fascinating to see how both techniques enhance storytelling in art. Thank you for the insightful analysis!

What a fascinating exploration of the differences between chiaroscuro and tenebrism! I especially enjoyed the way you explained the emotional impact of each technique. It’s intriguing how such subtle variations can evoke different feelings in the viewer. Thank you for shedding light on this topic!

This was a fascinating read! I always thought chiaroscuro and tenebrism were interchangeable terms, but your explanations helped clarify their distinct characteristics. The examples you provided really brought the concepts to life. Can’t wait to explore these techniques in more detail in my own art!

Great breakdown of the differences between chiaroscuro and tenebrism! I always thought they were the same, but your explanations helped clarify the nuances. The examples you used really brought the concepts to life. Thanks for sharing!

I have run into the same dilemma while exploring the work or Gentileschi, and I am so happy I found such a good explanation, thank you!

This post really clarified the differences between chiaroscuro and tenebrism for me! I always found both techniques fascinating, but I never grasped how they distinctively influence the mood and depth in artworks. Thanks for breaking it down so well!

What an insightful exploration of the differences between chiaroscuro and tenebrism! I never realized how the emotional impact of light and shadow could vary so dramatically between the two techniques. The examples you provided really helped clarify the distinctions. Can’t wait to see more posts like this!

I loved the detailed analysis of the differences between chiaroscuro and tenebrism! Your examples really helped clarify how each technique influences the mood and storytelling in art. It’s fascinating how artists use light and shadow to evoke emotion. Thanks for shedding light on this topic!

This post really clarified the differences between chiaroscuro and tenebrism for me! I always thought they were essentially the same, but the historical context and examples were super helpful. It’s fascinating how each technique influences the mood and depth of a painting. Thanks for such a thorough exploration!

I found this post really insightful! The distinction between chiaroscuro and tenebrism is often overlooked, but you explained it so well. I especially appreciated the examples you provided, which brought clarity to the differences between the two techniques. Looking forward to more art discussions like this!

This post beautifully clarifies the distinctions between chiaroscuro and tenebrism! I love how you highlighted the emotional impact of lighting in artwork. It’s fascinating to see how these techniques have influenced different artists throughout history. Thank you for such an insightful read!