“Art is based in fact, but made in fantasy.” Jules André Smith

The Man

Artist, architect, and writer Jules André Smith (1880–1959) left his Connecticut home in 1931, and headed to Miami to escape the cold northern winters and to set down roots. He was about 250 miles shy of his destination when he saw a beautiful sunset on Lake Sybelia in Maitland and decided to go no further. It was a fortuitous decision, as it was in Maitland that his dreams became reality.

Jules André Smith was born in Hong Kong to American parents, but his father was lost at sea when André was a little boy. His widowed mother moved to Germany for a few years, then in 1889 relocated to New York and eventually settled in Connecticut.

André first showed an aptitude for art in school but his mother’s misgivings about his pursuit of a career as an artist sent him to Cornell University to study architecture. In 1904, with both Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees under his belt, he took off for two years to study architecture in Europe on a Traveling Fellowship from Cornell.

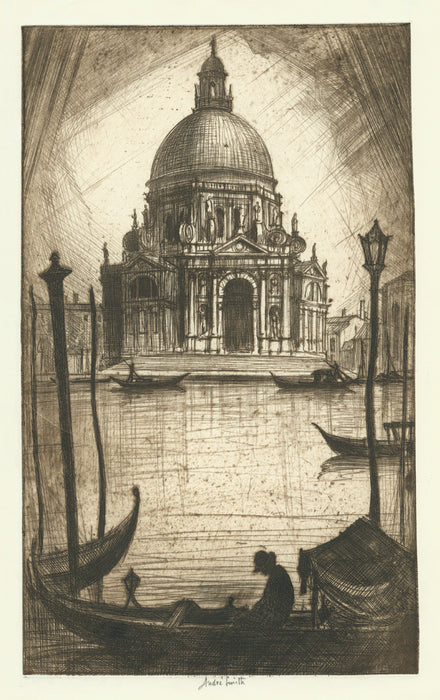

Santa Maria della Salute, 1914, etching on thin wove paper.

Hilltown, Southern France, n/d

Smith then worked for an architectural firm in New York City, pursuing etching and drawing on the side. By 1911 he had built a small following and he gave up his career in architecture to concentrate on art. He returned to Europe to travel and etch landscapes, and his work became increasingly experimental. In 1915, Smith was awarded the gold medal for etching at the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition in San Francisco. (The same expo where Gustave Baumann’s prints won the gold medal for color woodblock prints.)

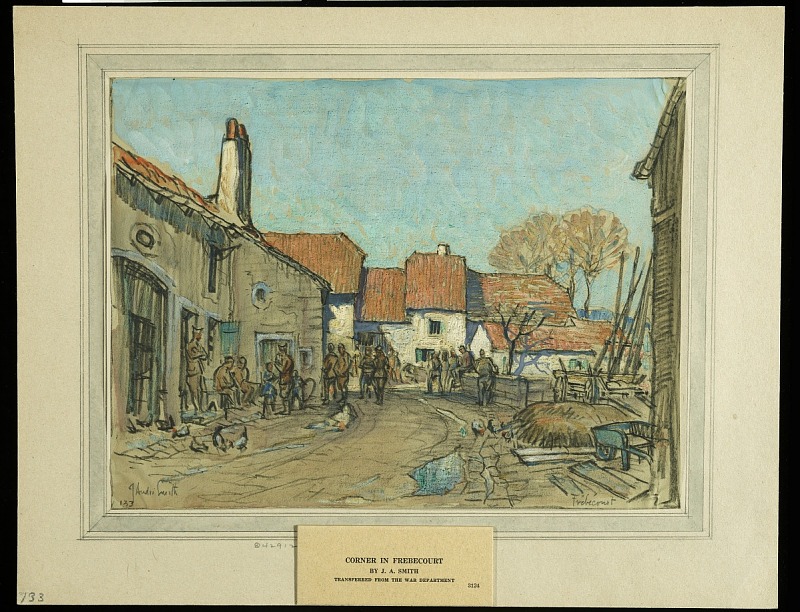

When the US entered World War I in 1917, Smith enlisted and was assigned to a unit of eight professional artists charged with documenting the American Expeditionary Force in France. (He also designed the Distinguished Service Cross which is still awarded today.) One result of his wartime experiences was a collection of 100 of his field sketches and drawings published in 1919, titled In France with the American Expeditionary Forces. This was the first of three books Smith would author, and its sober tone prefigured the sensibilities that characterized his later work.

Jules André Smith, c. 1917

The Road to Essey, 1918. Charcoal on white paper

A Billet Village on the Marne, 1918.

Charcoal and watercolor on paper

Corner In Frebecourt, c.1918.

Charcoal, pencil, and watercolor on paper

Another result of his military service was the amputation of his right leg. It had never completely healed after being injured on barbed wire during officer training, and in 1924 the leg had to be removed. It was disability that affected the rest of his life, and may, at least in part, have driven his decision to move to Florida.

His Patron

No sooner had Smith had settled in a rented house near Maitland, than his future began to unfold. Through a series of serendipitous introductions, Smith met Mrs. Mary Louise Curtis Bok. They shared a passion for the controversial “modern art” that was developing in the early twentieth century and commiserated over the lack of support for contemporary art in the vicinity. Intrigued by Smith’s vision of an artists’ compound where prominent American artists could live and work, experimenting with new art forms, Mrs. Bok offered to finance an artists’ residential laboratory.

In The Art Gallery, n/d

The Performer, ca. 1918

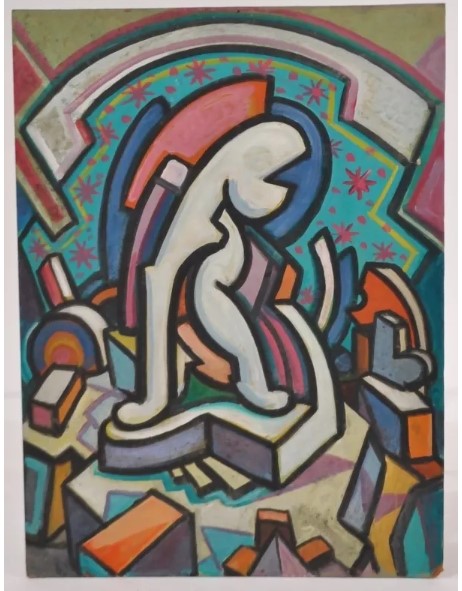

Untitled, n/d

At age 20, Mrs. Bok had married Edward W. Bok, then editor of The Ladies’ Home Journal, which was owned by her father’s publishing company. She first met Edward at age 13 when she began writing articles for the magazine. They purchased a winter home in Lake Wales, FL, and from there Edward pursued his passion, constructing the Mountain Lake Sanctuary and Singing Tower, now known as Bok Tower Gardens. While he did that, Mrs. Bok pursued her wide-ranging philanthropic interests which — in addition to the arts — included prison reform, medical research, US-Russian relations, the creation of a world criminal court, and establishing the American Peace Award. Edward died in 1930, and in 1943 she married a man 14 years her junior, Efrem Zimbalist Sr. who was Director of the Curtis Institute of Music, which she had founded in 1924.

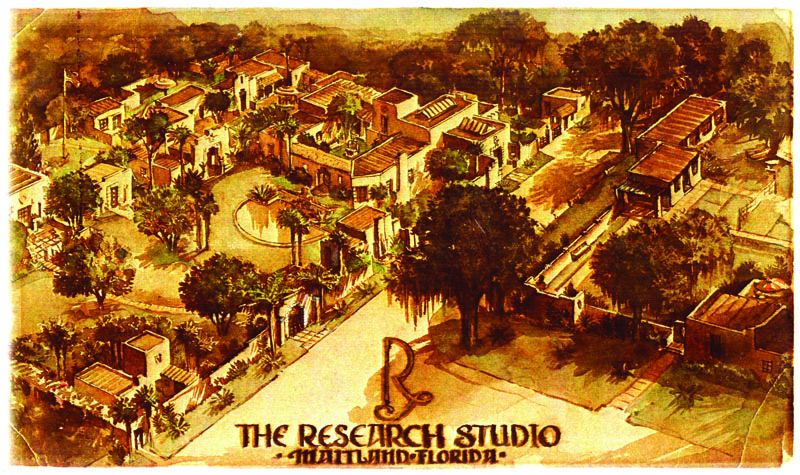

In 1937, Mrs. Bok provided the financing to buy six acres of land in Maitland, as well as to begin the first stages of construction of what was then called The Research Studio.

Over the next two decades, until his death in 1959, Smith lived and worked in the enclave, along with his closest personal friends Attilio and Florence Banca. The Bancas had moved with Smith from CT to help manage the artists’ colony, and their son was the only child to grow up at The Research Studio.

His Vision

Mayan Revival architecture, considered to be an off-spring of Art Deco, was popular in the 1920s and 1930s, especially for commercial buildings, although its application in residential construction was much less common. The archeological discoveries that were happening at that time excited the American imagination and interest in Aztec and Mayan culture.

Sometimes referred to as “fantasy architecture,” Smith’s personal interpretation of Mayan Revival style is a curious blend of influences. Architectural detail throughout the maze of hidden courtyards, gardens and twenty-two structures is ornate, the surfaces covered with sculptural reliefs drawing on Mesoamerican iconography mixed with colonial, Christian, and in some cases even Asian and African imagery.

University of Virginia architectural historian Richard Guy Wilson calls The Research Studio, “one of the most inspiring creations in the United States, in which you’re transported to another realm — almost a dream — which is the purpose of great works of art.”

The enclave Smith designed consisted of art studios, living quarters, and a gallery. Across the road from the live/work area, Smith built a recreation courtyard and garden, and an open-air chapel. For twenty-two years the colony was the winter residence of well-known artists such as Ralston Crawford, David Burlick, Ernest Roth, Milton Avery, Arnold Blanch, Doris Lee, Consuelo Kanaga and Harold McIntosh.

The Research Studio is an aesthetic masterpiece, created over 22 years by Smith’s singular artistic vision. By 1935 Smith’s eyesight had deteriorated so that he was unable to continue the close, detailed work necessary for etching, so he dedicated himself to embellishing the buildings and garden structures that he had designed. He hand-carved most of the center’s sculptural reliefs using a special pivot table that could turn upward that he invented.

Originally, the majority of the exterior bas-reliefs were hand-painted in vivid colors. But decades of sun, wind and rain erosion have taken their toll. “We didn’t restore the colors because there’s so much debate [among preservationists] over whether one can reproduce the master’s hand,” explained Bailey Cox, former executive director of the Art & History Museums Maitland. “We’ve left the exterior reliefs in their present condition, and now use them as educational tools to talk about the importance of preservation.”

Today

Jules André Smith died at his studio at the Research Studio in 1959, and was buried in his family’s plot near his Connecticut home. with his death, the colony closed, and the buildings sat dormant and deteriorating for ten years, in danger of being torn down. In 1969 the property was purchased by the city of Maitland, and in 1971 the compound was reopened as the Maitland Art Center.

While he frequently gave his art away to friends as gifts, it’s a sad fact that Smith’s work — which ranged in style from the realistic to the abstract — is held by few museums. He never exploited the success he enjoyed as a printmaker both before and after WWI. His print editions were small, and with no long-term dealer relationships his collector base was limited.

Smith’s legacy continues today through annual residency and studio programs that attract artists from across the nation. The nationally competitive Artist-in-Residence Program, which started in 2013, provides three-, six- or nine-week residencies that include studio space and housing.

This group of buildings is one of the only remaining examples of “Mayan Revival” fantasy architecture in the Southeastern U.S. Now the Maitland Art Center, it is home to a number of significant collections, including the artworks of its founder J. André Smith, Bok Fellows including Milton Avery, and contemporary Central Florida artists. The museum also holds the largest and most significant archive of Smith’s personal papers, correspondence, and estate artwork.

Maitland Art Center is listed on the National Register of Historic Places — along with more than 80,000 sites across the nation. However, it’s notable that the Maitland Art Center is among only 3% (just over 2,500) of those sites that have earned the more elusive National Historic Landmark designation. After a rigorous nomination and application process, and due in large part of the unique Aztec- and Mayan-influenced architecture, Smith’s Research Studio became a National Historic Landmark in 2014.

Hmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a little trip …

Maitland Art Center

231 W. Packwood Ave, Maitland, FL

407-539-2181

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the only search engine that makes it easy to discover almost 1700 art museums, historic houses & artist studios, and sculpture & botanical gardens across the US.

Just go to ArtGeek.art and enter the name of a city or state to see a complete interactive catalog of museums in the area. All in one place: descriptions, locations and links.

Use ArtGeek to plan trips and to discover hidden gem museums wherever you are or wherever you go in the US. It’s free, it’s easy to use, and it’s fun!

© Arts Advantage Publishing, 2023″

This is a very well written blog. You might find my 2022 catalogue “Teo for the Road: Ernest David Roth and Andre Smith in Europe, 1912-1930.” It was published by Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania in 2022, and shown at the Mattatuck Museum in Waterbury , Connecticut and in Washington, DC at the Stanford in Washington gallery. Let me know if you have difficulty finding it and I will send you a copy.

Eric Denker, author

ericdenker75@gmail.com