I’ve heard much about Black Mountain College over the years, and often wondered about its current status. So, on a recent visit to Asheville NC, I was on a quest. What I found was a wonderful little storefront museum in the Downtown Arts District that celebrates Black Mountain College (BMC). For almost 30 years, the Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center has explored BMC’s extraordinary influence on modern and contemporary art, dance, theater, music, and performance, educating the public about BMC’s history and long-standing impact as a forerunner in progressive interdisciplinary education.

It might be a surprise to learn that Black Mountain College was in existence for a mere 24 years, given the impact it has had on American culture, and its legacy of educational and artistic innovation. This small experimental college was started in 1933, located in what was then quite a remote location in western North Carolina mountains, outside the small town of Black Mountain. The college originally rented the YMCA Blue Ridge Assembly buildings south of Black Mountain, but In 1937 it purchased 667-acres across the valley at Lake Eden. In May 1941, following the end of their lease at Blue Ridge Assembly, the College moved its operations to Lake Eden, where it remained until its closing in 1957.

Students dancing in front of the YMCA building, before 1941

Studies Building, Lake Eden campus of Black Mountain College –constructed by the students & faculty, 1940-1941.

Conceived by John A. Rice — a brilliant and mercurial Classics scholar who had been fired from Rollins College for his controversial ideas and challenging attitudes – the founding of Black Mountain College (BMC) occurred simultaneously with the rise of Adolf Hitler and escalating persecution of artists and intellectuals in Europe. In 1933, the Nazis shut down the Bauhaus School, a similarly progressive arts-based educational institution in Germany. Many of the school’s faculty left Europe for the US, and a number of them settled at Black Mountain — most notably Josef Albers, who was selected to run the art program, and his wife Anni Albers, who taught weaving and textile design. (While Josef Albers led the school, the were only two required courses: one on materials and form taught by Albers, and a course on Plato!)

Walter Gropius, Bauhaus Building (1925-26), Dessau, Germany

Clemens Kalischer, Josef Albers’ Color Class, Summer 1948

The college was organized ideologically around John Dewey’s progressive philosophy, which emphasized holistic learning and the study of art as central to a liberal arts education. While usually thought of as an art school, in fact the arts were just one important element of a broader emphasis on the humanities and the importance of student involvement and hands-on learning.

That was not the only way in which BMC was fundamentally different. It was owned and operated by the faculty and was committed to democratic governance. All members of the college community participated in its operation, including farm work, construction projects, and kitchen duty — learning to enjoy process as much as product. The secluded environment fostered a strong sense of individuality and creative intensity.

Hazel Larsen Archer, The Path From the Dining Hall to the Studies Building, c 1948

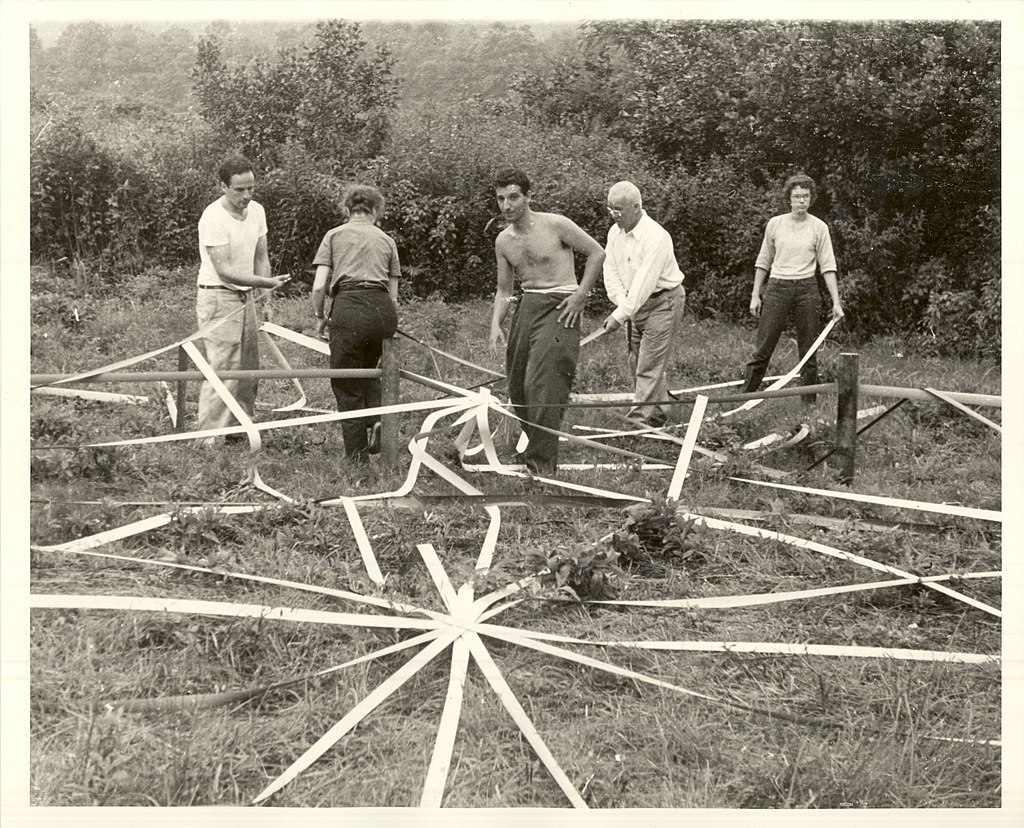

Buckminster Fuller and students assemble a geodesic dome, 1948

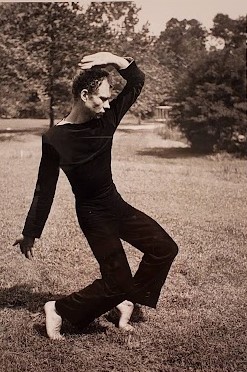

Hazel Larsen Archer, Merce Cunningham, early 1950s

BMC was legendary even in its own time. The school attracted and created maverick spirits, some of whom went on to become well-known and extremely influential artists, writers, poets, dancers, choreographers, and composers in the latter half of the 20th century. It was here that the first large-scale geodesic dome was made by faculty member Buckminster Fuller and students, where Merce Cunningham formed his dance company, and where John Cage staged his first musical “happening”.

In addition to Josef and Anni Albers, Fuller, Cunningham and Cage, notable teachers and students included Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Robert Rauschenberg, Jacob Lawrence, Cy Twombly, Kenneth Noland, Susan Weil, Ben Shahn, Ruth Asawa, Franz Kline, Arthur Penn, M.C. Richards, Francine du Plessix Gray, Robert Motherwell, Peter Voulkos, Dorothea Rockburne, Robert De Niro Sr, and many others in the pantheon of American arts. It was the BMC summer sessions in the arts — and the impressive lineup of visiting faculty who came to teach at them — that cemented its mythical reputation.

Alma Stone Williams — considered by some to be the first black student to enroll in an all-white institution of higher education in the South during the Jim Crow era — studied at Black Mountain College in 1944. Notable African-American instructors included Carol Brice and Roland Hayes during summer 1945; Percy H. Baker, hired on full-time in 1945; Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight during the 1946 Summer Art Institute; and Mark Oakland Fax for the Spring 1946 quarter.

The decline of BMC is a slow and sad tale — involving internal disputes, administrative conflicts, financial woes, FBI investigation, declining faculty and enrollment — and the enterprise officially closed in 1957. Two years before that, the sleeping lodges, dining hall and other structures on the lower campus had been taken over by a boys’ camp through a lease-purchase agreement. Camp Rockmont for Boys survives to this day.

Tours of the BMC campus at Lake Eden are offered … but not during the summer when camp is in session.

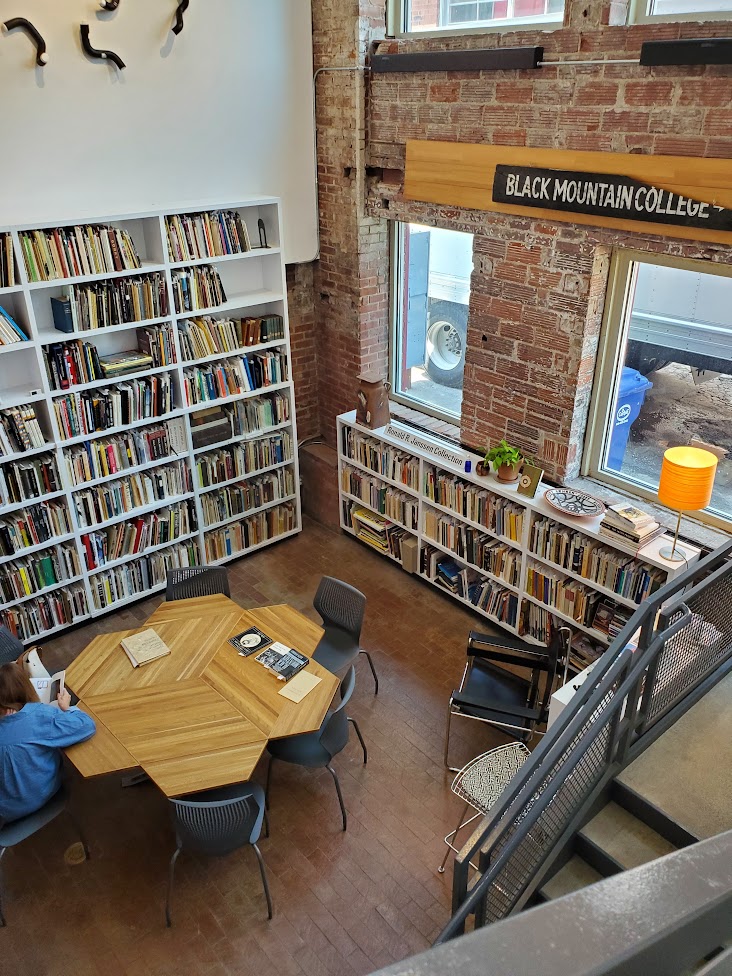

The BMCM+AC storefront façade is deceptive. Inside it is spacious, with exhibition galleries on two floors, a small shop area and library/research room to the rear of the lower level. The permanent collection of more than 4000 objects dates from the 1930s to the present, with works by alumni and students that trace the progression of their careers. The collection includes paintings, sculpture, photographs, ceramics, textiles, assemblage, furniture, blueprints, books and works on paper. The museum has also been facilitating oral history documentation since 1999, resulting in a collection of recorded interviews with fifty-eight BMC alumni to date.

Ground Level Gallery entrance

Lower Level Gallery and Shop

Library / Research Room

Pieces from the collection are used in rotating exhibitions, to illuminate connections between artists, objects, and the pervading atmosphere of experimentation and interdisciplinary influence at the College.

Two exhibitions were on display when we visited in early August.

Black Mountain College: Idea + Place (on view through Sept 3, 2022) explores how the influence of Germany’s Bauhaus and BMC’s isolated, rural, and mountainous setting during the era of the Great Depression and the Jim Crow South influenced the college community’s decision-making and the evolution of ideas.

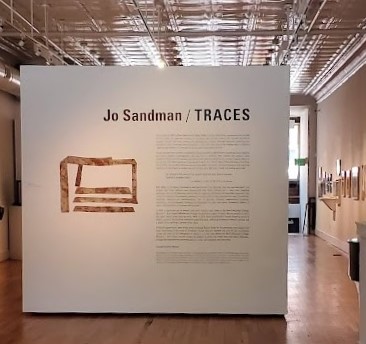

The other exhibition, Jo Sandman / TRACES (on view through Sept 3, 2022) is a retrospective representing the full range of work created by Boston-based artist and BMC alumna Jo Sandman.

Introduction to Jo Sandman

Installation view

At BMC during the summer session of 1951, Jo Sandman studied painting with Robert Motherwell and Ben Shahn; drawing with Joseph Fiore; photography with Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind; anthropology and French. It was this “galvanizing experience” at BMC that prompted Sandman to dedicate her life to art.

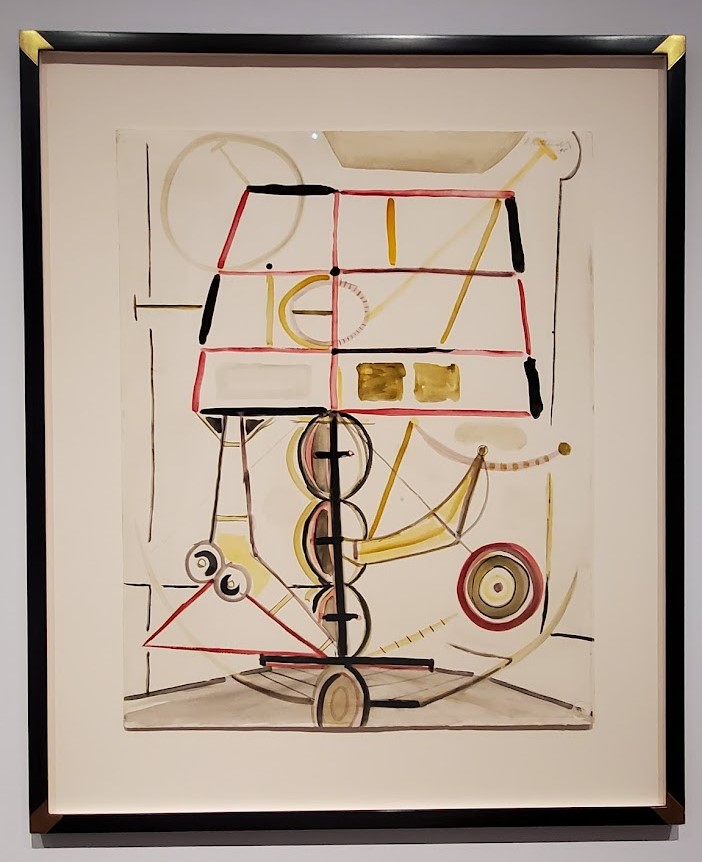

Robert Motherwell, Construction Drawing, 1945

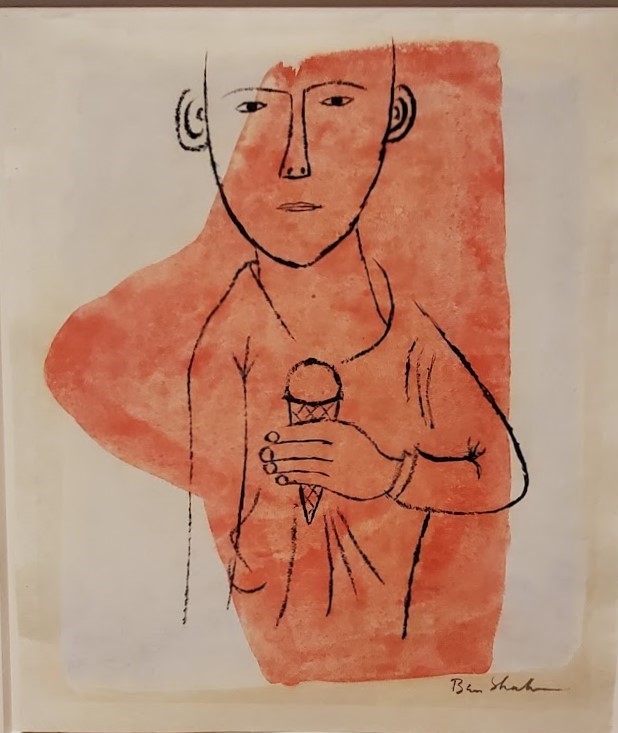

Ben Shahn, Study for Triple Dip, c. 1951

Jo Sandman, Clichy, c. 1960

She went on to develop and maintain a studio practice exploring painting, drawing, experimental sculpture, installation, and photography for more than sixty years. The exhibition manifests her restless curiosity which drove constant experimentation with a wide variety of imagery, materials, and processes.

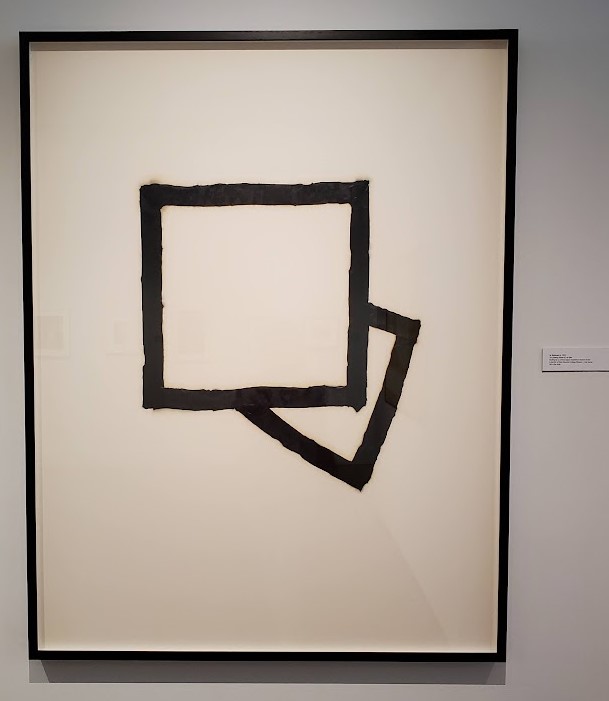

Jo Sandman, Tar Drawing Series #2, n.d.

Roofing tar on archival paper, on board

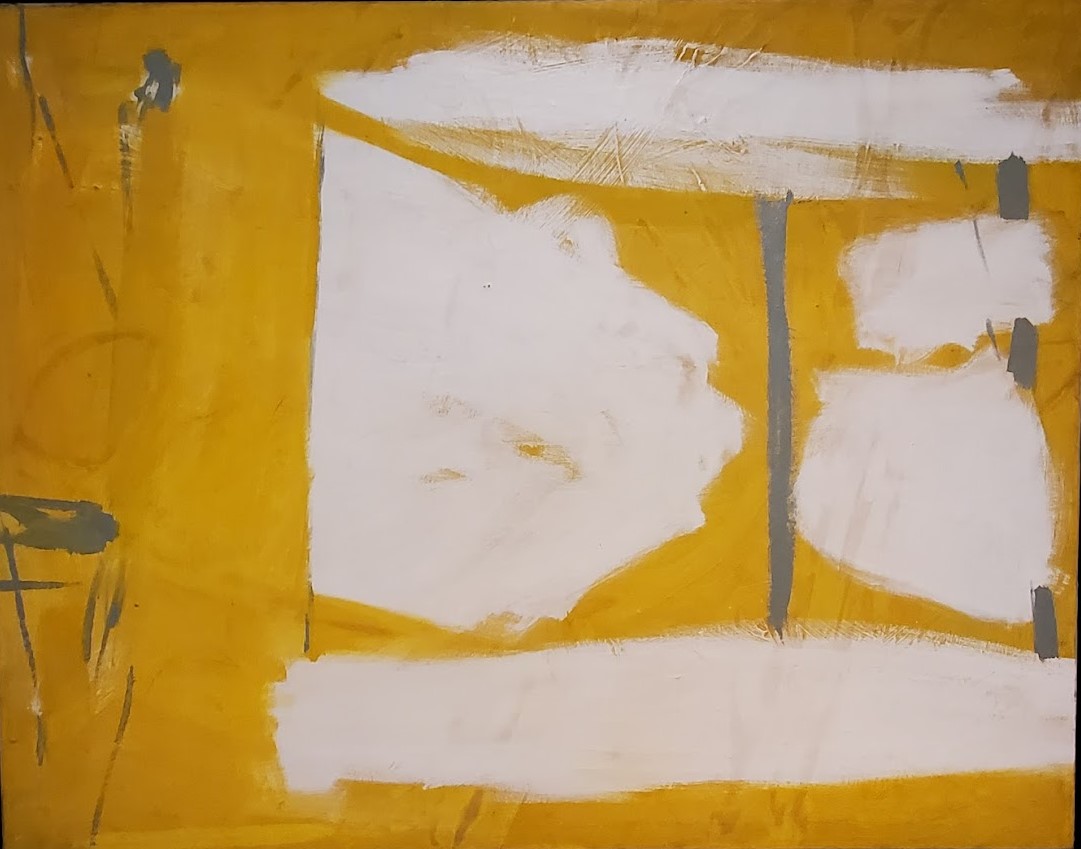

Jo Sandman, Untitled, 1952

Oil on canvas

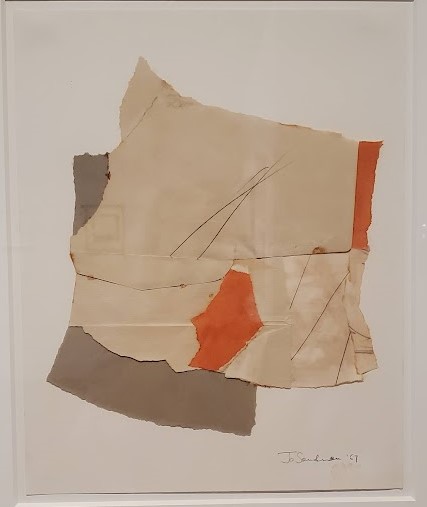

Jo Sandman, Untitled Collage, mid-1960s

Torn paper and paint on paper

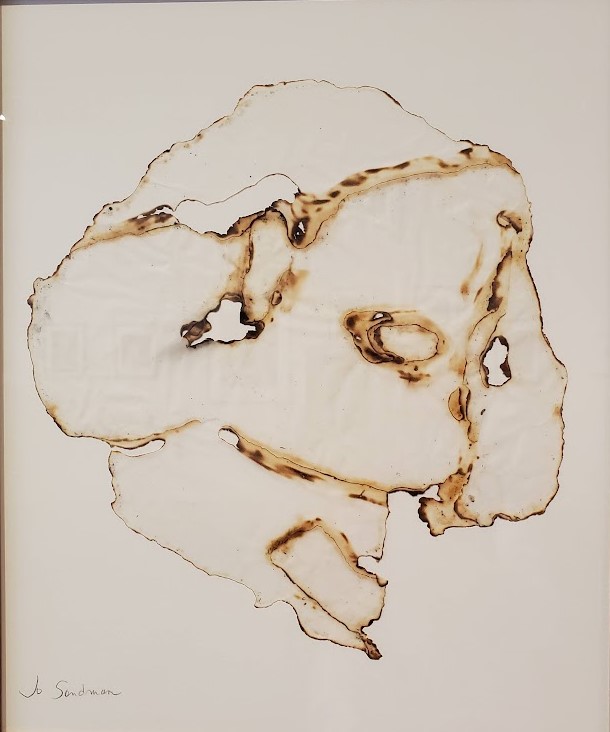

Jo Sandman, Untitled (Ignitions 24), 2000

Burned paper

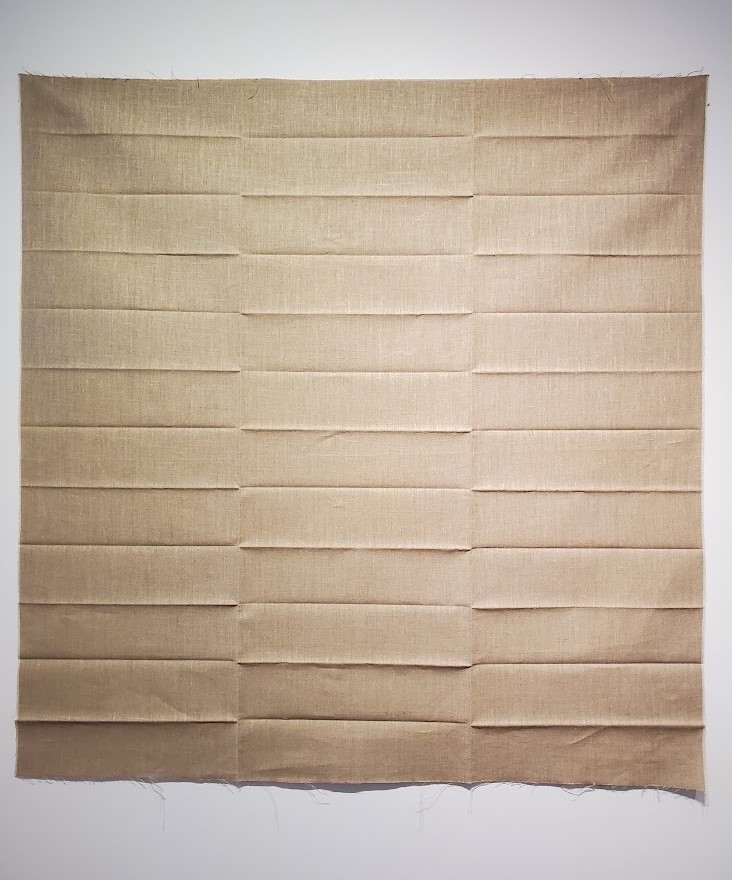

Jo Sandman, Grid, 1973

Folded, pressed Belgian linen

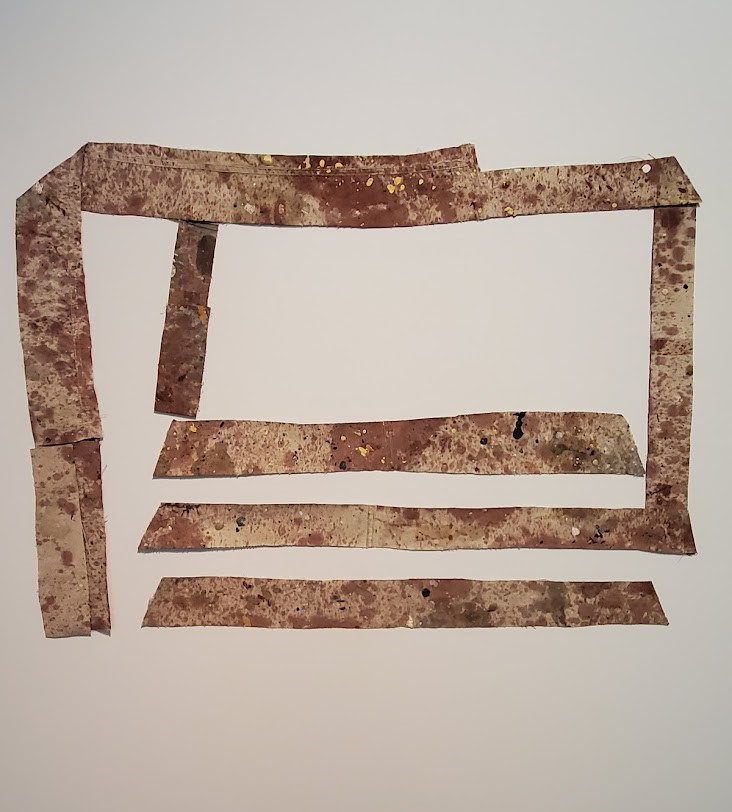

Jo Sandman, Tarp Series: Glyph, 1983

Collage, found painter’s dropcloth

Just last month, an article in the New York Times Style Magazine asked, nearly nine decades after the school’s inception, “Why Are We Still Talking About Black Mountain College?” Many people are “more than mildly obsessed with it. Indeed, this unusual, unaccredited little college in the middle of rural nowhere has been the subject of at least 10 full-length books and several poetry collections, and is a perennial topic of museum exhibitions. (…) Why the fascination? It is, of course, riveting to read about any group of artists — especially those whom we know would become famous in the fullness of time but who were still in the process of honing their craft, working and carousing together in anonymity, cross-pollinating ideas (and at times, with each other) and, ultimately, forming a community that amounted to more than the sum of its parts.”

In 1934, Josef Albers wrote in the Black Mountain College Bulletin:

“Art is a province in which one finds all the problems of life reflected.”

Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center provides an immersive and engrossing view into the legacy of this small, unaccredited college. Despite it’s short life, in many ways it can be said to have been a very successful experiment.

Hmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a little trip …

Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center

120 College St, Asheville, NC

828-350-8484

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the only search engine that makes it easy to discover more than 1600 art museums, historic houses & artist studios, and sculpture & botanical gardens across the US.

Just go to ArtGeek.art and enter the name of a city or state to see a complete catalog of museums in the area. All in one place: descriptions, locations and links.

Use ArtGeek to plan trips and to discover hidden gem museums wherever you are or wherever you go in the US. It’s free, it’s easy to use, and it’s fun!

© Arts Advantage Publishing, 2022