The First 3500 Years

More often than not, the paintings that really grab my attention are landscapes, and I like to think I’m a somewhat knowledgeable about them in terms of art history. So, I was surprised to learn recently that the word “landscape” — an anglicization of the Dutch landschap — was only introduced into the language as a term for works of art — around the start of the 17th century. That is not to say that landscapes didn’t exist in art before then … apparently there just wasn’t a word for them.

In Western art, the earliest existing example of a painted landscape is a fresco in Akrotiri, an Aegean Bronze Age settlement on the Greek island of Santorini. The walls of one room are covered with stylized lilies (or papyrus) sprouting from colorful volcanic rocks, with swallows flying among the flowers. It was beautifully preserved under volcanic ash from 1627 BC until about 50 years ago.

circa 3,500 years ago

Elements of landscape were also depicted in Ancient Egypt, often as a backdrop for hunting scenes set in the reeds of the Nile Delta. In both cases, the emphasis was on individual plant forms and figures on a flat plane, rather than the broad landscape. A rough system of scaling, to convey a sense of distance, evolved as time went on and as the decorating of rooms with frescoes of landscapes and mosaics continued through the Hellenistic and ancient Roman periods.

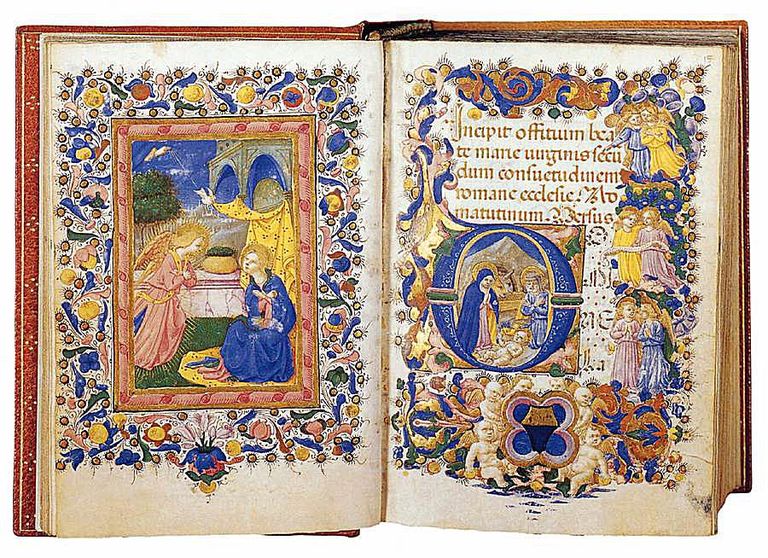

The Renaissance brought a real breakthrough with a new system of graphical perspective. This allowed expansive views to be represented convincingly, with a natural-seeming progression from the foreground to the distant view.

Szépmüvészeti Múzeum, Budapest

The word perspective comes from the Latin perspicere, meaning “to see through”; the application of perspective comes from mathematics.

The basic geometry is this: 1) objects are smaller as their distance from the observer increases; and 2) an object’s dimensions along the line of sight are shorter than its dimensions across the line of sight, a phenomenon known as foreshortening.

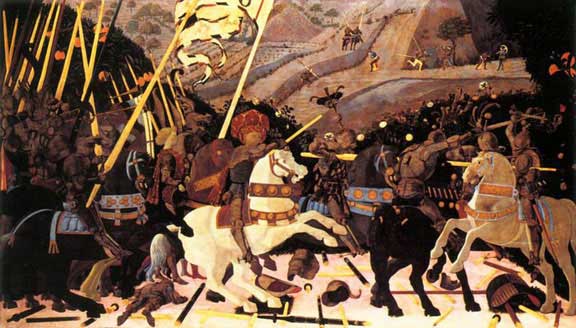

Despite artists having learned to render exemplary middle-distance and far-distance panoramas, until the 19th century landscape painting was relegated to a low position in the accepted hierarchy of genres in Western art. However, narrative painting — typically biblical or mythological stories — was highly prestigious, and for several centuries Italian and French artists simply turned landscape paintings into history paintings by adding figures to make a narrative scene. In England, landscapes mostly figured as backgrounds to portraits, suggesting the parks or estates of a landowner.

Metropolitan Museum, New York, NY

In the Netherlands, pure landscape painting was more quickly accepted, largely due to the repudiation of religious painting in Calvinist society. Many Dutch artists of the 17th century specialized in landscape painting, developing subtle techniques for realistically depicting light and weather.

National Gallery, London

Certain types of scenes repeatedly appear in inventories of the period, including “moonlight,” “woodland,” “farm,” and “village” scenes. Most Dutch landscapes were relatively small: smaller paintings for smaller houses.

National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

In fact, the genre was so broadly accepted in the Netherlands in the 17th-century that landscape artists were called the “common footmen in the Army of Art” by the Dutch Golden Age painter and theorist Samuel van Hoogstraten.

Subsequently, in the 18th and 19th centuries, religious painting declined throughout the rest of Europe. That fact, combined with a new Romanticism — which emphasized emotion, individualism, and the glorification of nature — promoted landscapes to a firm position in the hierarchy of genres.

Schloß Charlottenburg, Berlin

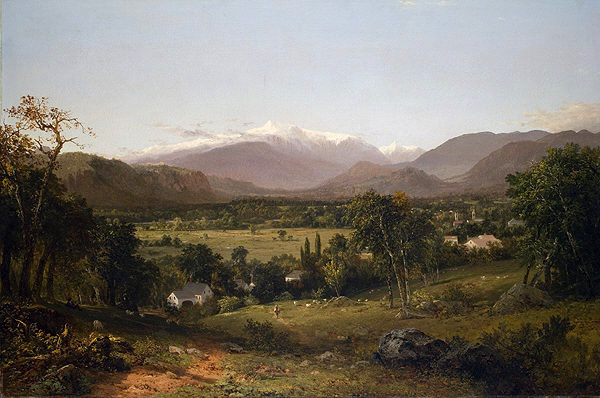

In the early mid-19th century in the United States, landscape painters of the Hudson River School were influenced by Romanticism and an ethos of exploration, They depicted the natural beauty of the new nation, from the Hudson River Valley and other Eastern locales to the vast American West. They documented — and often idealized — the ruggedly sublime wilderness which was fast disappearing.

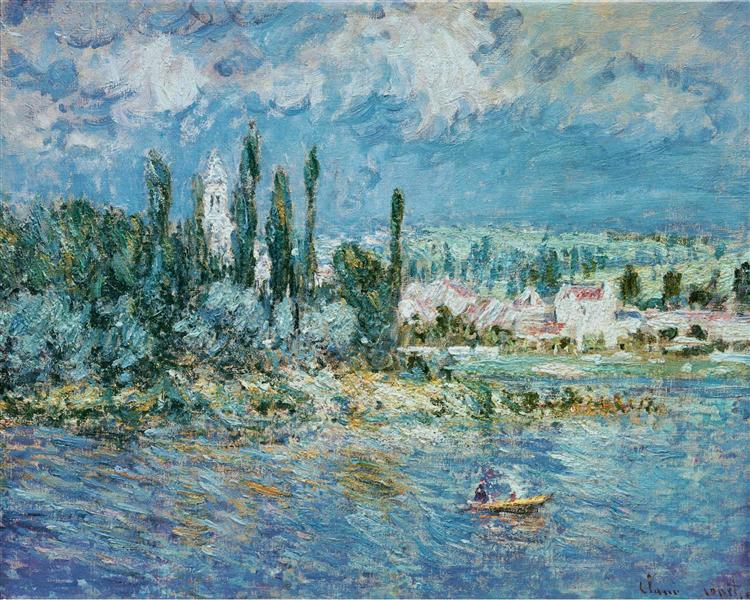

In the meantime, French painters in the Barbizon School were establishing a landscape tradition that would become the most influential in Europe for a century. By the late 1860s a younger generation had been influenced by the Barbizon painters. Taking landscape a step further, Impressionism was born. Often painting “en plein air” (outdoors), the Impressionists introduced radical stylistic innovation for the first time in a very long time.

While they also painted still lifes and portraits, street scenes and interiors, Impressionist landscapes firmly established the genre as one of the most well-loved in art — then as now.

Folkwang Museum, Essen, Germany

There is so much more! But this is meant to be a quick romp through the landscape of landscape-art history so, with this, I’ll leave the pursuit of more depth on the subject to you and Google. Have fun and enjoy the vistas!

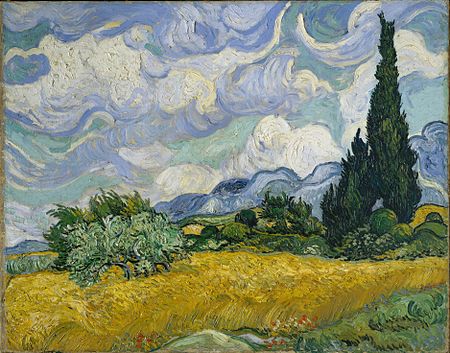

Banner image: Vincent van Gogh, Wheat Field with Cypresses, 1889, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the search engine that makes it easy to discover more than 1300 art museums, historic houses & artist studios, and sculpture & botanical gardens across the US. Just enter the name of a city or state to see a complete catalog of museums in the area. All in one place: descriptions, locations and links.

https://waterfallmagazine.com

Thanks for finally writing about > A Quick History of Landscape Painting in Western Art – ArtGeek < Loved it!

So much more to read and research! Your introduction has opened up many questions to be explored. Excellent writing.

Thanks for your comment, Tobi! Glad you enjoyed this “quick history” of landscape art.