The Norton you may have known once-upon-a-time is not today’s Norton.

While the excellent collections are not new, the stunning architecture is. While the location is the same, the address is not. And the restaurant gets our vote for the best museum cuisine we have yet to experience! We love that American museums are taking it up a notch, interpreting their 21st century role in ways that go beyond the need for greater collection and exhibition diversity.

Founded almost 80 years ago, the Norton Museum of Art has built a distinguished collection of American, European, and Chinese art, and is building its holdings of photography and contemporary art. Masterpieces of 19th century and 20th century European painting and sculpture include works by Brancusi, Gauguin, Matisse, and Picasso, and American works by the likes of Moran, Hopper, O’Keeffe and Pollock.

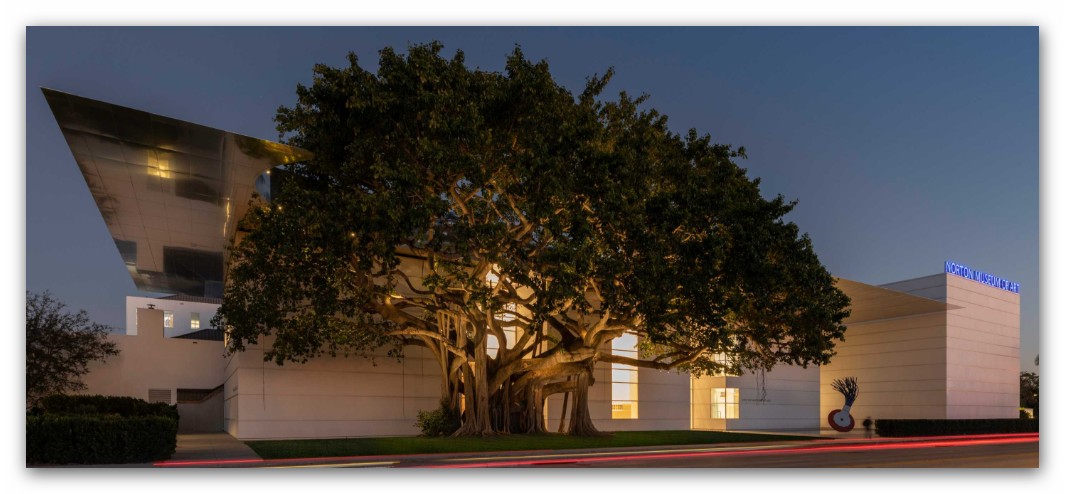

Constructed in 1941, the Art Deco-inspired museum building was laid out in a series of one-story pavilions embracing a central courtyard. The logic of that original structure is still very much in evidence but is now wrapped in architecture of the 21st century.

Last year, after a 7-month closure and an investment of $100-million, a magnificent new Norton Museum of Art was unveiled.

The museum entrance has been reoriented to face west, to the main thoroughfare of South Dixie Highway, turning its back on S. Olive Avenue. Almost 60,000-square-feet were added in a West Wing, increasing gallery space for the collection of more than 8000 works by 35%.

Three spacious, double-height pavilions now welcome visitors, connecting the older low-rise galleries with a new three-storey wing and unifying the different heights of the various sections. The contemporary west façade is clad with a pristine manmade white stone.

The entry plaza features a 43-foot-high lustrous metal marquee that curves around the canopy of a magnificent banyan tree. Centered in the forecourt is a reflecting pool that surrounds a 19-foot-tall sculpture, Typewriter Eraser, Scale X (1999) by Claes Oldenburg and his wife, Coosje van Bruggen.

The 6.3-acre campus includes a sculpture garden, invitingly landscaped with native trees and flowering plants, shady walkways and a grassy lawn for outdoor programs. The south side of the garden is lined with a series of 1920s-era houses that have been restored to serve as the director’s home as well as lodging and studios for a new artist-in-residence program that will begin this year.

When we arrived, we thought it was awkward that the Norton’s parking lot is located across a busy road from the Museum itself. Later we learned that the parking area had previously been adjacent to the building, but it was sacrificed to create the new garden. Strolling the paths on a gorgeous Florida winter day, we decided it was a trade-off worth making!

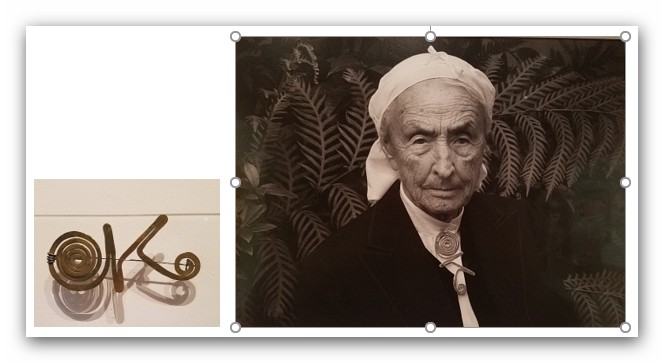

Onthe day of our visit, the special exhibitions gallery was thronged with Georgia O’Keeffe fans. This was the last stop for the Georgia O’Keeffe Living Modern exhibition (Nov 22, 2019 – Feb 2, 2020) which had been touring the country since the Spring of 2017.

Having lived for some years within a stone’s throw of the O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe NM, we didn’t expect to see much that was new to us. So we were happily surprised by the novel curatorial approach — exploring how O’Keeffe used what she wore to manage her public image, and how she controlled her portrait photographs taken by the likes of Alfred Stieglitz, Ansel Adams, Annie Leibovitz, Cecil Beaton, Andy Warhol, Todd Webb, among other illustrious photographers. Dozens of pieces from O’Keeffe’s wardrobe were accompanied by text about her habits of dress as well as iconic photographs showing her personal style and public persona.

“Oh, she wore black. Black, black, black. And her clothing was all like men’s clothing. … (S)he didn’t believe in lace, or jabots in blouses, laces or ruffles or things like that. everything on straight lines. –”

A student of O’Keeffe’s in Canyon, TX

One of many engaging reveals was the story of the brass pin that Alexander Calder designed for O’Keeffe, playing on the upper-case letters of her last name. Although designed to be worn horizontally, O’Keefe preferred to position it vertically. She often wore it when sitting for photos. Apparently, when her hair turned grey she thought the brass color unflattering, so she had a silver version made and never again wore Calder’s original.

With the O’Keeffe show now closed, the next special exhibition, Robert Rauschenberg: Five Decades from the Whitney’s Collection, is set to open February 21, running through June 28, 2020. The exhibition will trace five decades of Rauschenberg’s career and feature highlights from various series that demonstrate his constant experimentation.

Organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, it promises fascinating exposure to Rauschenberg’s (1925–2008) embrace of popular culture in his art. The way he incorporated everyday objects into his art forever changed the American art landscape, anticipating pop art, conceptualism, happenings, and process art of the latter 20th century. Worth seeing!

Special exhibitions come and go, but the collections remain, filling the Norton galleries with delights as far-ranging as a Chihuly Persian Sealife Ceiling (2003); a colossal Tang Dynasty Buddah Head (c 673- 705); a Portrait of Mr. Justice Beard (1782) by George Romney; a small Henry Moore Family Group sculpture (1946); and Nature Morte Portugaise (Portuguese Still Life) (1916) by Robert Delaunay.

Henry Moore (British, 1898-1986)

Family Group, 1946

Robert Delaunay (French, 1885-1941) Nature Morte Portugaise, 1916

Although the Collections have steadily grown through donation and acquisition, the Museum was founded in 1941 on the collection of industrialist Ralph Hubbard Norton (1875-1953) and his wife Elizabeth Calhoun Norton (1881-1947). Their initial approach to art was for decorating their home, but soon Ralph became interested in art for its own sake. Over time he acquired a sizable collection of paintings and sculpture and ultimately founded a museum to make it accessible to the public.

[Note that the nearby Ann Norton Sculpture Gardens is an entirely separate institution. The sculptor Ann Norton was Ralph’s second wife and widow. She lived and worked in the historic home, studio and gardens, which are now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.]

Norton’s principal interest was in American painting and sculpture of his time – the first half of the 20th century – so the Museum’s holdings are particularly strong in that area, with notable oil paintings by George Bellows, Charles Demuth, Edward Hopper, Georgia O’Keeffe and Robert Motherwell; and watercolors by Charles Burchfield, Winslow Homer, and John Marin, among many others.

Ralph Norton also gave 130 works of Chinese art to the Museum, and the collection has continued to grow over the years. Today it numbers more than 700 objects that span 5000 years of Chinese aesthetic history.

European holdings include painting, sculpture, and works on paper from 1300 to 1945, and represent all the major artistic movements from the Renaissance through Impressionism and Modernism.

Bequest R. H. Norton

As we moved through the European galleries we repeatedly noticed paintings that had been gifted by Valerie Delacorte, whom we later learned was an Hungarian film actress, philanthropist and writer. With her second husband, George Delacorte, she amassed an exceptional art collection over the course of 30 years, and in 1991 she made her first donation of five Old Master paintings to the Norton Museum. Ultimately, the Museum’s European Collection was transformed by her generosity — with gifts amounting to more than 60 paintings and works on paper.

Gift of Valerie Delacorte in memory of George T. Delacorte

As admirers of landscapes, we were engaged at separate moments by two works by artists we admire. Both painted in oils, they were conceived 100 years and an ocean apart, by Charles-François Daubigny and Richard Diebenkorn. Each is layered with foreground, middle ground and sky; in each the eye is drawn across the picture plane from left to right; and yet …

C.-F. Daubigny (French, 1817-1878) Landscape with a Pond and Cottage, 1863

Richard Diebenkorn (American, 1922-1993), Landscape with Figure, 1963

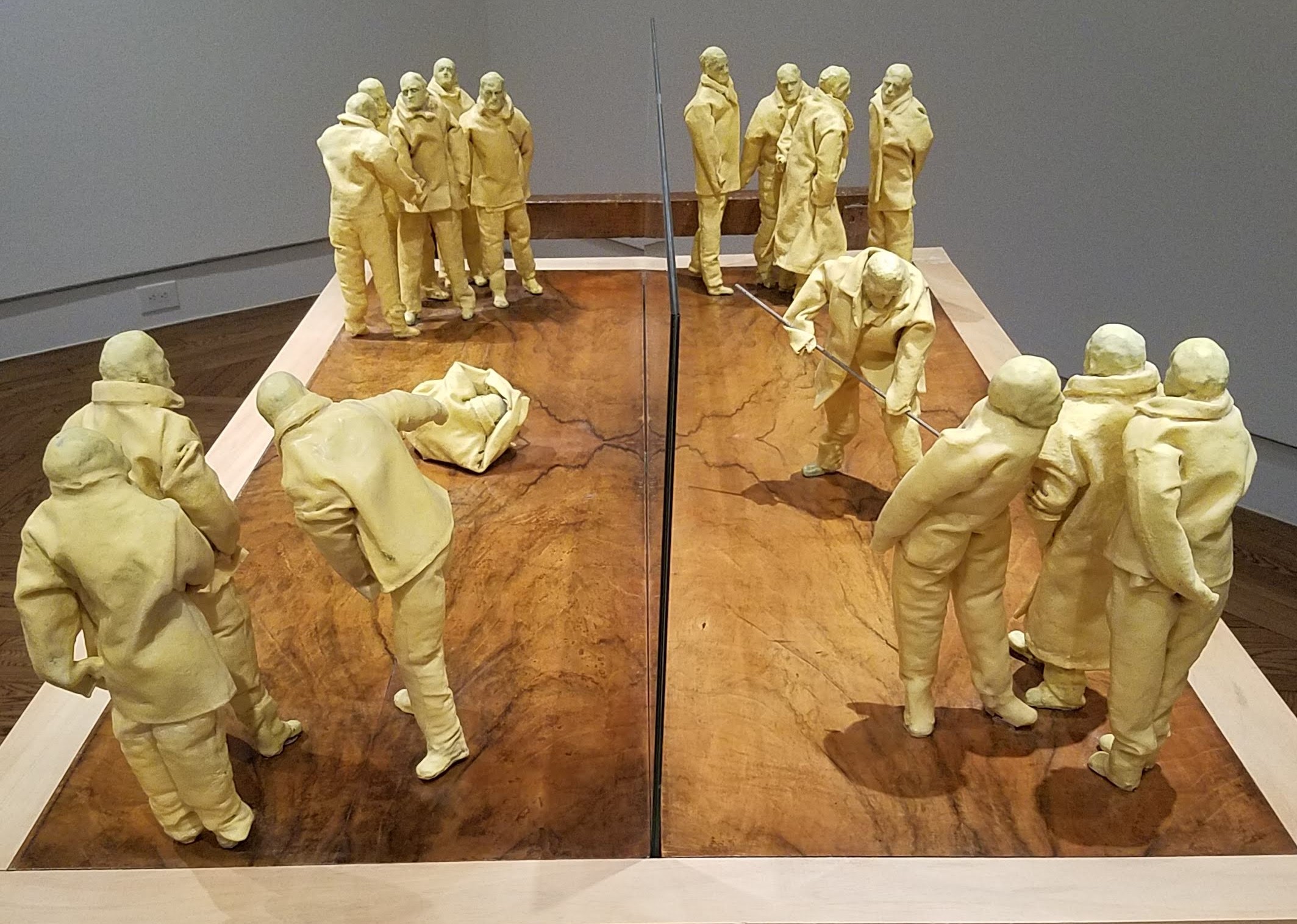

The Contemporary Art Collection and Photography Collection are somewhat recent developments. Photography holdings, initiated in 1998 by yet another transformative gift, are rich in works by European modern masters; mid-century American photographers; and contemporary, international photographers. In 2009 a dedicated Curator began to oversee the Collection of Contemporary Art. An area of enthusiastic donor activity, gifts and acquisitions of the art of today have added breadth to the Museum’s holdings, instilling a strong global voice and greater diversity.

Gift of Camille O. Hoffman in loving memory of Paul W. Hoffman

As for The Restaurant at the Norton, as it’s called, arriving exactly at noon on a Friday we were fortunate to snag the last two available seats. Although we’d hoped for a table on the covered terrace, we accepted stools at the bar and were engaged by a friendly and efficient tag-team of servers, congenial fellow-patrons, and an excellent menu that delivered on its promise. An extra fun fillip was the 39-minute video compilation of trompe l’oeil art-antics by Gregory Scott (American, born 1957) that animated the far wall.

To be assured a place at the time of your chosing for a truly exceptional museum lunch, our advice is to make a reservation immediately upon arrival at the museum — or even call ahead. Although this may not be necessary other days, it is especially the case in season, on Friday and Saturday when Museum admission is free.

Norton Museum of Art

1450 S. Dixie Highway, West Palm Beach, FL

561-832-5196

Hmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a little trip?

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the search engine that makes it easy to discover more than 1300 art museums, historic houses & artist studios, and sculpture & botanical gardens across the US.