A quick study: Who was Jusepe de Ribera? Who was St. Paul the First Hermit? And why did the artist paint the saint?

The Snite Museum of Art at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, has recently received an exciting long-term loan — from the Cummins Family Collection — of the painting St. Paul the Hermit by Jusepe de Ribera (Xàtiva 1591 – Naples 1652).

Recognized today as one of the greatest of the Baroque masters, Ribera was born near Valencia, in Spain. He is considered a leading painter of the Spanish school, although he lived and worked on the Italian peninsula –for his entire artistic career — never returning to Spain.

As a young man Ribera longed to study art in Italy and he made his way there while he was still a teenager. He stayed first in Parma, and then was living in Rome by 1612. That was two years after the death of Caravaggio, who had shaken the art world to its core with his confrontational pictorial honesty and his innovative treatment of light, using extreme contrasts of light and dark (chiaroscuro) to emphasize narrative, gesture and expression.

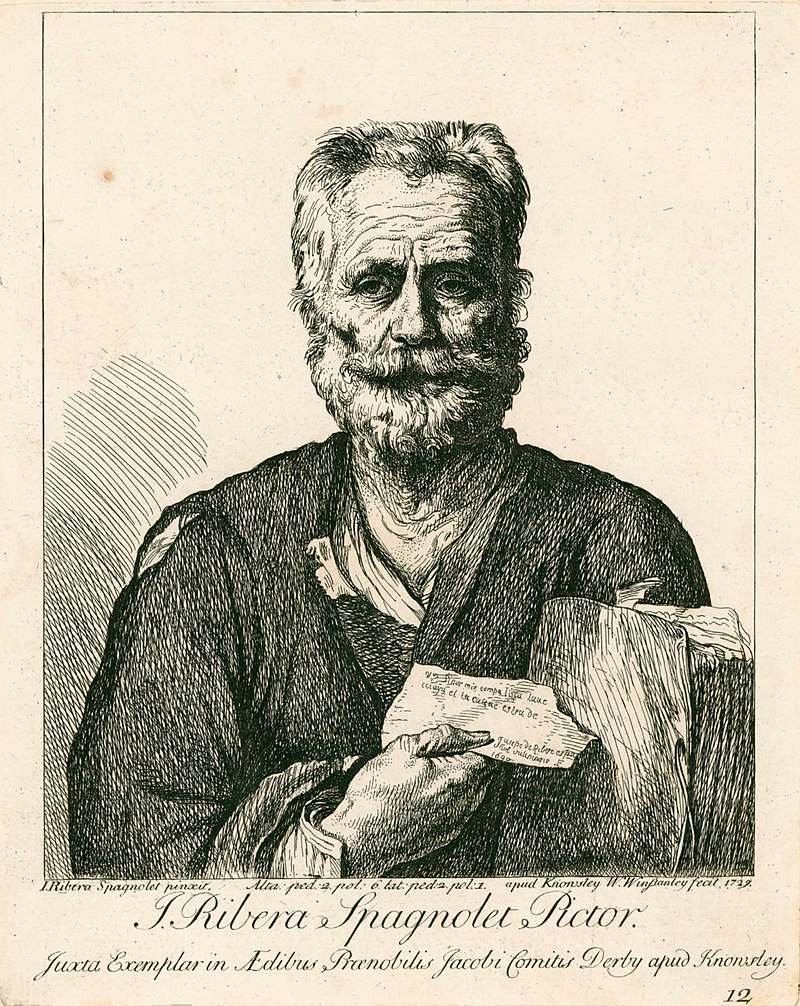

Ribera was just one of many artists inspired by Caravaggio who flocked to Rome from elsewhere in Italy and Europe in those years. Known as Caravaggisti, many of them – including Ribera — found lodgings in the artists’ quarter around Via Margutta, just inside the Northern entrance of the city. He became known by his contemporaries, critics, and collectors as “lo Spagnoletto” (The Little Spaniard).

Oil on canvas 163 x 233 cm. Galleria Corsini, Rome

Ribera was perhaps the pre-eminent champion of the new naturalism. The influence of Caravaggio can be seen in Ribera’s strong contrasts of light and shadows, and his emotive figures depicted with unforgiving realism.

“Spagnoletto tainted / His brush with all the blood of all the sainted”

Lord Byron (Don Juan, xiii. 71)

Ribera was also influenced by the work of the Bolognese artists Annibale Carracci (1560 –1609) and Guido Reni (1575 – 1642) who had been students of Florentine and Venetian painting. They revived an interest in the Platonic ideal of beauty.

“Carracci’s frescoes [in the Farnese Palace in Rome] convey the impression of a tremendous joie de vivre, a new blossoming of vitality and of an energy long repressed”.

Rudolf Wittkower, British art historian

During his time in Rome Ribera would have studied Carracci’s lively frescoes. A subtle restraint in figural composition and forceful, precise gestures often seen in Ribera’s work reveal his familiarity with works of the artists from Bologna.

Despite having a substantial income, Ribera lived beyond his means and in 1616, to escape his creditors, he relocated to Naples. The Kingdom of Naples was then part of the Spanish Empire, ruled by a succession of Spanish Viceroys.

Naples had not been an important city during the Renaissance, but in the 17th century it became a leading cultural and commercial center, and the most active Mediterranean port. With a population of 450,000 in the early 1600s, it was the second largest city in Europe, after Paris, and three times the size of Rome.

Ribera was quickly accepted into the Spanish governing society, as well as the merchant community from Flanders — another Spanish territory — which included influential collectors and dealers in art. Ribera began to sign his work as “Jusepe de Ribera, español” (“Jusepe de Ribera, Spaniard”). Just a few months after his arrival, he married the daughter of a prominent Sicilian-born Neapolitan painter, whose connections in the local art world helped to establish him early on as a major player.

From the late 1620s he was viewed as the leading painter in Naples and he received the Order of Christ of Portugal from Pope Urban VIII in 1626.

Ribera’s presence in Naples bore a lasting impact on the art of the city – as well as that of Spain. The Viceroys collected paintings to adorn their own Neapolitan palaces and family chapels, and they were also charged by the Spanish king to buy paintings for him. Thousands of paintings by Ribera and other artists working in Naples were sent home.

One notable example provides a sense of the scope of this transfer of art to Spain: the Count of Monterrey — who was viceroy from 1631-1637 — took forty shiploads(!) of paintings and classical sculptures home with him when his assignment to the Kingdom of Naples ended.

This helps explain why Ribera’s influence can be seen in the work of Velázquez, Murillo, and most other Spanish painters of the period, and accounts for all the Ribera works held in Spanish collections today — despite his never having returned to his homeland.

This excerpt from Brill’s A Companion to Early Modern Naples distills the dominance and energy of the Church in Naples in those days:

“Naples was a center of prodigious artistic production in the early modern period. For ecclesiastic institutions, 16th & 17th century Naples was one of the largest cities in western Europe and the capital of a kingdom that was perilously close to the expansionist Ottoman empire. As such it was a prime theater for the implementation of institutional reform and parochial outreach …; it was also eagerly colonized by recently founded religious orders such as the Discalced Carmelites, … and accommodated the renewal efforts of orders of much earlier foundation, including the Benedictines, Franciscans, and Carthusians.

These orders built imposing chapter headquarters in Naples or had their preexisting complexes rebuilt or renovated, contributing to a city-wide construction boom in the 17th century. … Attracted by [favorable] social and economic incentives, the aristocracy … constructed family palaces and endowed chapels in the city’s churches.”

Ribera’s oeuvre includes mythological subjects, portraits of ancient philosophers, and genre portraits. But this flourishing Catholicism caused Ribera to also paint innumerable religious pictures to fulfill the demands of the pious Spanish/Neapolitan society in which he lived for 40 years.

Namesake saints were a common subject for private commissions throughout Catholic Europe, and certainly no less so among private collectors in Naples for decorating their homes and the high altars and family chapels of the 500-plus churches in the city. What may be a bit unusual in Naples, though, is the relative number of portraits of hermits that Ribera and others painted. They certainly weren’t uncommon in other parts, but the prominence of hermitic orders in that city may have driven a greater-than-usual interest in portraits of iconic hermits.

Why Hermits?

The contemplative orders of Carthusians and Carmelites were extremely influential in the religious life of the city. Both orders had roots in the hermitic tradition, emphasizing ascetic solitude and silence. They looked far back in time to pre-Christian Jewish hermits as their spiritual ancestors, thus portraits of esteemed hermits epitomized their aspirations.

During the Counter-reformation of the 16th century two Spanish saints, Saint Teresa of Ávila and Saint John of the Cross, reformed the Carmelite Order. It was then that the mendicant Order of Discalced Carmelites was established — discalced being derived from Latin, meaning “without shoes.” This Spanish heritage gave the order significant status in Naples.

The Carthusian monks had had a presence in Naples for some time, and during the 17th century boom the community at San Martino grew, enlarging their charterhouse and undertaking an intensive decoration campaign at the monastic complex. From the 1620s through the 1650s, they commissioned canvasses from at least thirteen different painters, including Jusepe de Ribera.

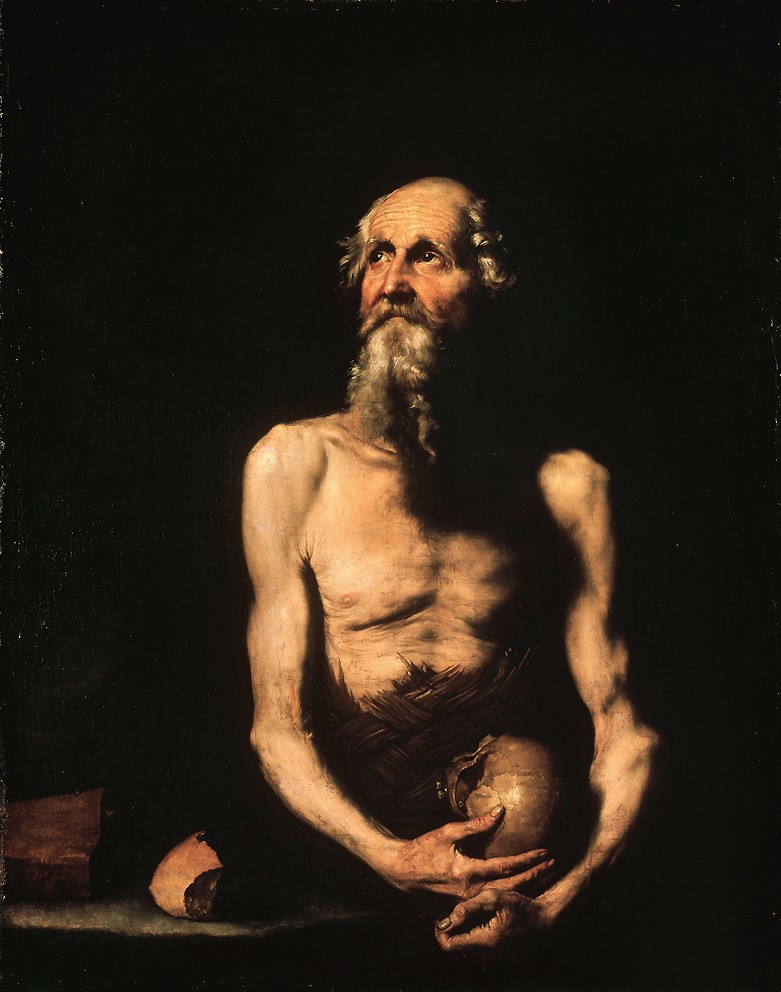

For their rejection of worldly goods and pleasures, and their concentrated and undistracted worship of God, hermit saints were very much venerated. We know of at least ten hermit portraits attributed to Ribera.

Carstanjen collection, Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln

These paintings have certain attributes in common: we see a bearded old man with no meat on his bones, wearing a rough covering. Almost always a skull – long used as an aid to meditation and symbolizing the transitory nature of life and the vanity of worldly pursuits — is shown as a reminder of the inevitable equalizing-effect of death.

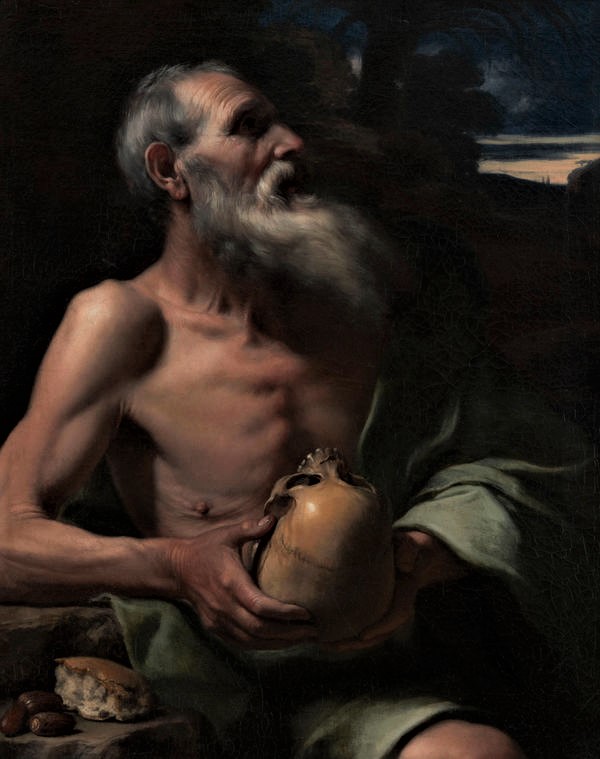

Louvre, Paris, France

Why St Paul the Hermit?

As the hermitic orders trace their spiritual ancestry back to the pre-Christian Jewish hermits, it makes sense that the first known Christian hermit would hold a significant place in the chronicles of eremitical history.

Saint Paul the Hermit is believed to have been the first Christian to lead a solitary life of divine devotion in the desert, and he was the first hermit to be canonized. Born in Thebes (now Luxor), Egypt, he fled into the desert to avoid the persecution of Christians, and to dedicate his life to the solitary worship of God.

Paul was orphaned when he was about 15, during the time of Emperor Trajanus Decius’ persecution of the Church (A.D. 250). As a Christian, he was forced to spend much of the ensuing years in hiding, protected by friends. When he was 22, his sister’s husband connived to expose him to the authorities as a means of gaining control of the assets Paul had inherited. To avoid arrest, he escaped into the desert, expecting to return once the persecutions had eased. But he found that the hermitical life suited him, and the peaceful solitude of the desert seduced him to stay.

According to legend, Paul was born in the year 228 and lived for 113 years until his death in 341. He resided for ninety years in a desert cave, following a rigorous routine of constant prayer and meditation. His nourishment consisted of dates from a palm tree and, after he had lived in solitude for twenty-one years, his legend has it that a raven began to bring him a daily portion of bread sent by God. A freshwater spring provided him with water.

St. Jerome wrote down Paul’s story, without the apochrypha of the bread-bearing raven. In his words,

“Conforming his will to the necessity, Paul fled to the mountain wilds to wait for the end of the persecution. He began with easy stages, and repeated halts, to advance into the desert. At length he found a rocky mountain, at the foot of which, closed by a stone, was a cave …, and saw within a large hall, open to the sky, but shaded by the wide-spread branches of an ancient palm. … a fountain of transparent clearness…. Accordingly, regarding his abode as a gift from God, … and there in prayer and solitude spent all the rest of his life. … kept himself alive on five dried figs a day.

St. Jerome

Iconographic guides indicate that Paul, the First Hermit, is usually shown as an aged man dressed in a girdle woven of palm leaves. There is almost always a skull in the scene, there may be a handful of dates and/or a chunk of bread, and often the presence of the apocryphal raven that brought the daily bread from God. Other items that refer to Paul’s story may be shown, such as the two lions that are said to have dug a hole for his grave.

It’s worth noting that not all these attributes are to be seen in any single depiction of St Paul the Hermit. Nor is the skull and bread iconography exclusive to St. Paul. These often appear in images of other hermits and contemplatives — so unless researchers have uncovered original documentation and can track provenance for a painting — it is entirely possible that subject attributions have changed over the years. Safe to say, though, if there’s a girdle woven of palm fronds, or dates, you’re looking at St. Paul the Hermit.

St. Paul the Hermit by Jusepe de Ribera

St. Paul the Hermit, ca. 1614-1615

Oil on canvas, 34 ¾ x 29 inches (87.5 x 73.5 cm)

On long-term loan to the Snite Museum of Art

Image courtesy of the Cummins Family Collection

Prominently displayed in the foreground of Ribera’s St. Paul the Hermit from the Cummins Family Collection are the God-sent loaf and three dates from the desert palm tree. In his sunburned hands Paul cradles an upward-facing skull as he looks heavenward, his gray beard, creased face and the loose skin of his torso indicative of his advanced age.

These motifs—the haggard depiction of an elderly bearded ascetic, the remarkably natural portrayal of the skull, and the isolation and devotion of the subject—were to become hallmarks of Ribera’s work. We see these features repeated in all his hermit portraits. Here, they are contrasted with a distant, almost romantic landscape of a dark blue sky looming over a rocky promontory, relieving the tenebrist background.

Ribera deviated here from St. Paul the Hermit’s traditional iconography of the palm-frond girdle. The green fabric of Paul’s robe is perhaps a nod to that tradition. We know that Ribera was familiar with the palm-frond iconography, as he used it in other portraits of this saint, so we might speculate that the robe here refers to the cloth tunic that St. Anthony the Great wrapped around Paul’s body for burial.

The realistic still life of bread and dates and the skull in St. Paul’s hands show Ribera’s Spanish roots. But the spare figural composition, the bathing light and deep shadows, and the background landscape show the influence of Central Italian painting on the young artist.

Art historian Tomaso Montanari has described the softer and lighter style that emerged in Ribera’s work in Rome, where he would have studied the Carracci’s exuberant frescoes and other work of Bolognese painters. Montanari notes that the St. Paul the Hermit from the Cummins Family Collection is exemplary of that style. (It is thought to have been painted shortly before the artist’s move to Naples.)

“Ribera’s half-length portrait of a saint is a stunning example of Counter-Reformation devotional art popular in the seventeenth century, and it richly complements the University’s collection of Italian religious narratives,” said Cheryl Snay, Curator of European Art at the Snite Museum of Art. “Moreover, the artist’s emphatic naturalism and dramatic tension make it as compelling now as it was four centuries ago.”

Hmmm… Maybe it’s time to plan a little trip?

Snite Museum of Art at the University of Notre Dame

100 Moose Krause Circle, Notre Dame IN

574-631-5466

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the search engine to easily find more than 1300 art museums, historic houses and artist studios, and gardens across the US.