Three important historic plantations are located in a row along Ashley River Road, about 15 miles NW of downtown Charleston. Just past Trader Joe’s on Rte 61 we suddenly found ourselves cruising through a verdant wooded suburb that held a promise of bucolic delights.

The other Trader Joe’s

Of the three National Historic Landmarks located within a five-mile stretch, we visited Drayton Hall and Middleton Place. Visited in sequence, they bring clarity to the distinction between preservation and restoration. (To learn more, read our article, Exploring the Difference: Preservation vs Restoration).

First up, standing tall around a bend at the end of a long unpaved lane is Drayton Hall. In contrast to most house museums, it is preserved in “its state of survival and the purity of its condition” — without modern conveniences like plumbing or central air-conditioning and heat — as it was when the National Trust for Historic Preservation acquired it from the seventh generation of the Drayton family.

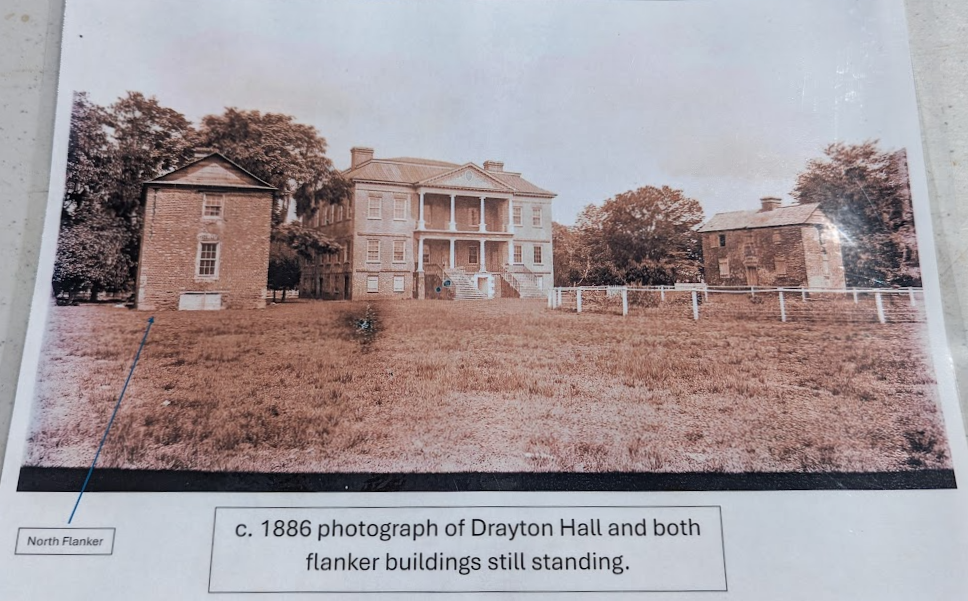

Drayton Hall, begun in 1738 by John Drayton (c.1715 – 1779), is thought to be the earliest example of Palladian architecture in the United States. John Drayton’s extensive library included nine architectural pattern books written by English neopalladian designers, including that of Colin Campbell. These served as references in constructing Drayton Hall, which was built as a Palladian five-part plan, with colonnade walls connecting the main house to two brick flanker buildings.

Palladianism first emerged in Britain in the work of the Scottish architect Colen Campbell (1676 – 1729). His book Vitruvius Britannicus, or The British Architect (1715) highlighted all the key Palladian features: a focus on symmetry, proportion and balance, with one side of the building a mirror image of the other; the use of temple fronts (a pediment supported by Corinthian columns or pilasters) and large tripartite Venetian windows. It also featured a rusticated basement – a lower floor which contained masonry blocks with a rough, rustic appearance that contrasted with the smooth finish of the building at a higher level.

Victoria and Albert Museum

Front elevation

Rear elevation

The house has a double projecting portico on the west facade, which faces away from the river and toward the land side approach from Ashley River Road.

Given that Drayton Hall is widely considered to be the earliest and finest example of Palladian architecture in the United States, one might expect its design to be the work of an experienced architect. But research indicates that the architect was very likely John Drayton himself. Among the architectural elements in Drayton Hall that are clearly attributable to these books are two classically-inspired overmantels that appear in William Kent’s, Designs of Inigo Jones, and James Gibbs’ A Book of Architecture. Considering the extravagant cost of acquiring such volumes and the education necessary to utilize them, the architectural books in John Drayton’s library offer valuable insight into his wealth and intellect.

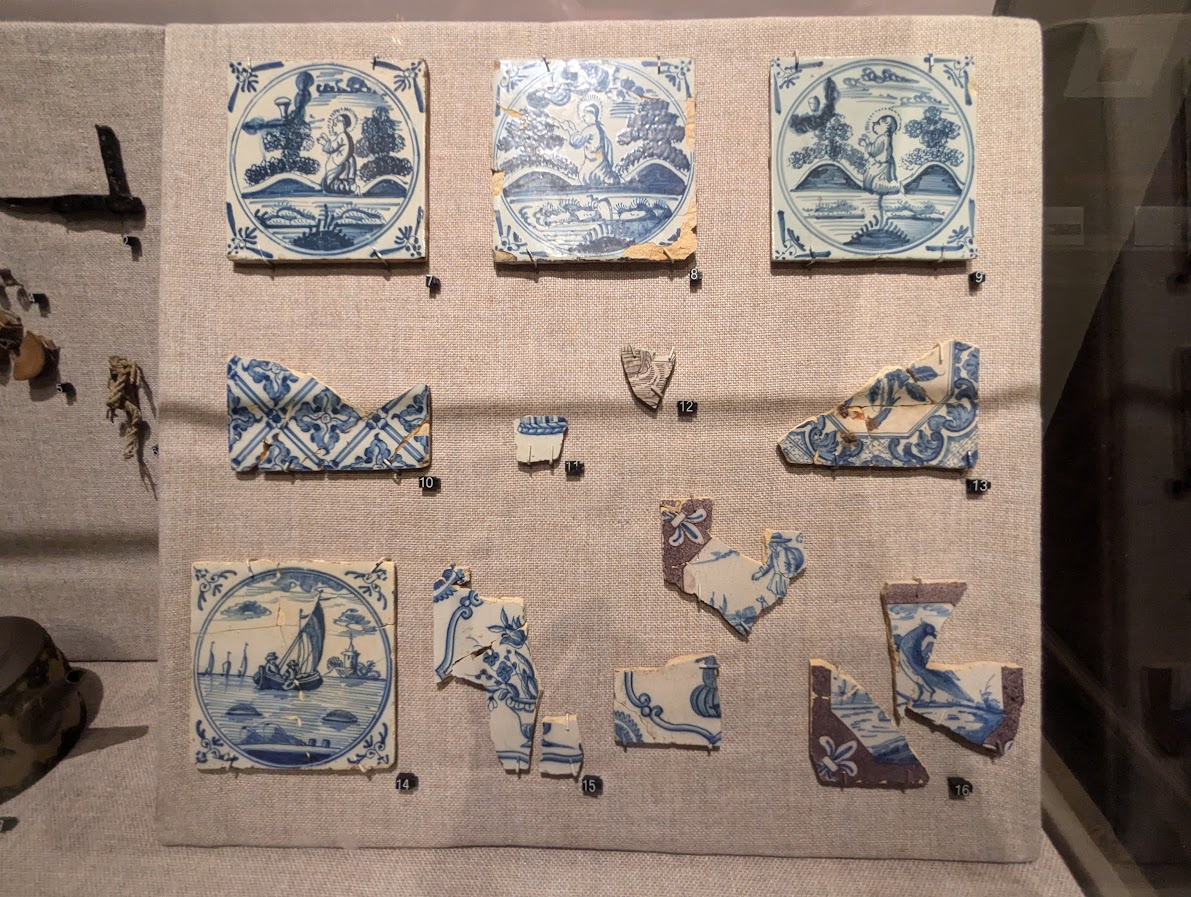

The north and south flanker buildings no longer exist, and where the north flanker stood is now a dig site. Major excavations of two-thirds of the structure conducted in 1981 and 2008 uncovered 18th century artifacts including ceramics, wine bottles and furniture hardware. The exact purpose of the building remains unknown, but archeological evidence suggests that its use changed over time, at one point functioning as a summer kitchen. Recently, armadillo activity around the north flanker’s masonry foundation has turned up several 18th century artifacts, prompting new archeological excavations to begin on the previously unexplored portion of the building.

Today, Drayton Hall has a preservation department dedicated to researching the historic architecture, landscapes, archaeology, and decorative arts associated with the site, with two full-time archaeologists on staff. It is an active archaeological site that has already yielded more than 1 million artifacts, although only 2% of the property has been excavated. Since the house is not air conditioned or heated, these artifacts are selectively displayed in a climate-controlled gallery in the Visitor Center.

Decorative Tableware

Architectural Ornaments

Delft Tiles from fireplace surround

Excavated Staffordshire teapot fragments, and intact example acquired in England in 2015.

Chinese export porcelain fragments recovered from the South Flanker well (Early 18th century)

In addition to excavated artifacts, the gallery displays furnishings donated to the Drayton Hall Museum Collection by Drayton family members and others.

Settee, England or Scotland, c.1750.

Mahogany with beech seat frame

Chinese Export Porcelain, 1740-1750.

4 surviving plates from set of 12

Mahogany Desk & Bookcase, England c.1750. (Recent conservation revealed 13 hidden comparments!)

Unlike other plantations along the Ashley River, Drayton Hall is the only authentic colonial period home dating to the 18th century. The other plantation homes were burned to the ground during the Union’s march into Charleston at the very end of the CIvil War. Local historians believe that Drayton Hall survived because of rumors that the house was a hospital for contagious smallpox patients, and that Dr. John Drayton, who served as a Confederate surgeon, posted yellow quarantine flags at the property’s entrance to warn Union troops away.

Whether the quarantine flags were a real warning or a ploy, we can be grateful that it worked. Drayton Hall was left standing for later generations to explore and learn from.

Although the Civil War didn’t destroy Drayton Hall, the family was left penniless, their Confederate currency worthless. Subsequent phosphate mining on the grounds returned the family to prosperity, but by 1973 the cost of maintaining the property had become a strain and they sold it to the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

The house had never been abandoned, so why does it look so forsaken? With phosphate mining ocurring on the poperty, the family moved into Charleston in 1886. They built a caretaker’s cottage to ensure the house would be well-maintained and secure, and from then on — for decades — Drayton Hall was only used as an occasional weekend and summer home.

By 1926, only a daughter, Charlotta, and her younger brother Charles were still alive. “Charlotta was greatly attached to the house – in its original, romantic, state – untouched by modernity,” says Mark Meredith, founder of HouseHistree. “Today, the house is singular among any other like it for having neither plumbing nor electricity. It was considered, but the work would have caused irreversible damage to its original features and as the family only intended to continue using it as a vacation home, they felt no need for it. In winter, Charlotta used a single wood-burning stove for heat; and, in summer she allowed herself a refrigerator, but took the power from a lead run all the way across from the caretakers house!” She referred to her time at Drayton Hall as “camping”

In order to preserve the seven generations of history within its walls and on its grounds, the radical decision was made to stabilize the house rather than restore it to a particular period, and to preserve it as it was acquired from the family in the 1970s.

Indeed, it is not “fully dressed” as are Middleton Place and most other historic homes we visit. (To learn more about Middleton Place, read our article Discovering Middleton Place, Charleston SC.) What we see at Drayton Hall are the the bare bones, allowing us to fully appreciate the layout, the architectural detail, and the evolving history of the house. The structure has been stabilized and will be maintained into the future at this level of preservation.

The missing pieces of this ceiling medallion will not be replaced

The fireplace in the privy

The basement kitchen

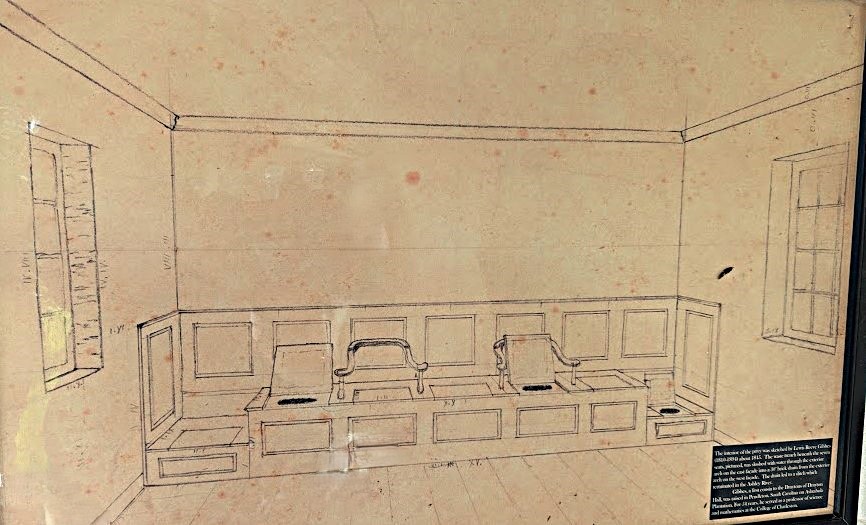

Two outbuildings remaining on the 630-acre property are the Caretaker’s House and the privy. An earthquake destroyed the laundry house (South Flanker) in 1886, a hurricane destroyed the kitchen in 1893, and in 1969 Hurricane Hugo knocked down a 19th-century riverside barn. Thirteen slave cabins — which are believed to have housed approximately 78 slaves — once formed a small village in the woods between the house and the main road. Their burial ground stands nearby, now the oldest documented African-American cemetery in the nation still in use.

African-American cemetery

Privy

Caretaker’s House, c.1870

Design drawing for privy interior

View of Garden from Welcome Center

The cultural history of the site plays a big part in the visitor’s experience. Drayton Hall could not have been what it was for generations but for the enslaved people who lived and labored on the property, and their reality is treated with tremendous respect by the curators. Their stories deserve to be told.

We recommend taking the short drive from the historic center of Charleston to visit Drayton Hall. Study the timeline wall. Watch the introductory video. Linger in the lovely garden. Take the guided tour. Step into the Caretaker’s house and learn about its residents and the structural changes it underwent as their needs changed. Spend two or three hours on the property for a journey through almost 400 years of American history.

A visit to Drayton Hall is highly recommended!

Hmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a little trip …

Drayton Hall

3380 Ashley River Rd, Charleston, SC

842-769-2600

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the only search engine that makes it easy to discover more than 1700 art museums, historic houses & artist studios, and sculpture & botanical gardens across the US.

Just go to ArtGeek.art and enter the name of a city or state to see a comprehensive interactive listing of museums in the area. All in one place: descriptions, locations and links.

Use ArtGeek to plan trips and to discover hidden gem museums wherever you are or wherever you go in the US. It’s free, and it’s easy and fun to use!

© Arts Advantage Publishing, 202By 1926, only a daughter, Charlotta, and her younger brother were still alive.