On Plantation Row along the Ashley River west of Charleston are three magnificant properties, with Drayton Hall and Middleton Place flanking Magnolia Plantation. All three have stories to tell, featuring large in both local and US history.

Drayton Hall was built in 1738 by John Drayton (c.1715–1779) — the great-grandson of Thomas Drayton Jr., who founded Magnolia Plantation in 1676. Although John was born at Magnolia, he knew that, as the second son, he was unlikely to inherit the family homestead, so he purchased acreage next door to the east and established his own plantation. (Read Discovering Drayton Hall in Charleston, SC to learn more.)

When John’s son Charles (1743-1820), married Hester Middleton, her home, Middleton Place was owned by her eldest brother Arthur (1742-1787). With the union of Chareles and Hester, Drayton blood joined the Middleton lineage. (Even a cursory reading of Charleston-area history turns up repeated mention of Draytons and Middletons playing leading roles in local affairs.)

Located four miles west of Magnolia Plantation, Middleton Place remained in the family until Middleton descendants transferred ownership to the Middleton Place Foundation in the early 1970s.

Today the estates flanking Magnolia Plantation stand as exceptional examples of two distinct ways to maintain historic properties. (Read Exploring the Difference: Preservation Versus Restoration to learn more).

Arthur Middleton was a signer of the U.S. Declaration of Independence and he helped design the state seal of South Carolina. He retired from Congress in 1777 and returned home to run Middleton Place. In 1778, the British forces had taken Savannah and then moved on to Charleston. Arthur was taken prisoner and held captive for a year while Middleton Place was looted and vandalized — but not burned — by British troops. Arthur returned in 1782 and spent the last five years of his life restoring his property.

Rendering of Middleton Hall — Main House and Dependencies –before 1865

Arthur’s eldest son, Henry Middleton (1770-1846), continued the family political tradition as a state senator and subsequently as the 43rd Governor of South Carolina. From 1820 to 1830, he was the U.S. Minister to Russia. On returning to Carolina, he became a leader of the Union Party. In 1755, Henry added dependencies to either side of the three-story mansion in order to accommodate his extensive library and a conservatory, to the south, while also creating a gentleman’s guest wing to the north.

Henry and his wife had ten children who lived to adulthood. It was their fifth son, Williams Middleton (1809-1883), who remained at Middleton Place. He made numerous choices that left their mark on the property. Amusingly, he bought cashmere goats from Tibet, he was one of nation’s first farmers to use barbed wire, and he imported the first water buffaloes from Constantinople — today Istanbul, Turkey — to till the rice fields.

Almost century after the British ravaged the property, troops from the North invaded yet again, and this time Middleton Place fared less well. Unlike his father, Williams supported the Confederacy, which meant that in February, 1865, in the final months of the Civil War, a detachment of Sherman’s army ransacked the plantation and set fire to the main home and dependencies. They also butchered five water buffaloes for food, and three of those that were spared later showed up in New York’s Central Park Zoo.

Only the south dependency building was not irreparably burned, and Williams repaired it with money borrowed from his siblings. In 1886 an earthquake caused the collapse of the final vestiges of the ruined mansion and north dependency.

By 1870 the Middletons had returned to live again at Middleton Place and the rebuilt south flanker building continued to serve subsequent generations until becoming a House Museum in 1975. The plantation is now a National Historic Landmark District and is home to the oldest landscaped gardens in the United States.

Remains of mansion after the Civil War

Remains of the mansion today

The view from what was the center hallway of the mansion

Middleton Place today, once the south dependency

The rebuilt structure today presents a fascinating slice of American history, told through the lives and accomplishments of generations of a single family. Most notable are the collection of furnishings and decorative arts — many acquired in Russia by Henry in the early 19th century — and the extraordinary gardens. Most poignant are the juxtaposition of a copy of the Declaration of Independence (1776), signed by Arthur Middleton, with a copy of the South Carolina Ordinance of Secession (1860), signed by his grandson, WIlliams Middleton — and the contrast between the way of life of the land-owners and the slaves and freedmen who labored there.

We opted for a scheduled guided tour of the house, with an extremely engaging and knowedgeable docent, rather than a self-guided walk-about. Every room reflects the interests, refined taste and resources of the Middleton family. Notable among the period furnishings and family heirlooms were portraits by Benjamin West and Thomas Sully; fine Charleston and London-made silver; a pre-revolutionary breakfast table made by Thomas Elfe who was Charleston’s most celebrated cabinetmaker, the aforementioned rare facsimile copy on silk of the Declaration of Independence, and first edition works by Mark Catesby, John James Audubon and other significant artists and authors.

Dining Room

Mahogany Breakfast table

Parlor

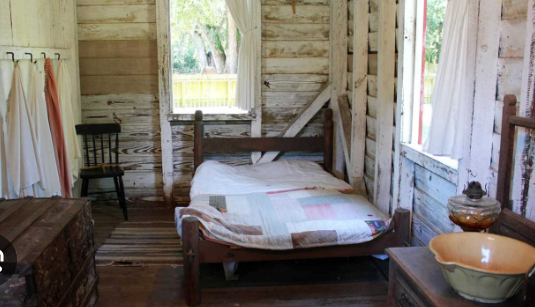

“Summer” Bedroom (headboard and bed hangings removed)

Wanting to capture and share pictures of the exquisite collection of original art, furniture, documents and other objects that were used and treasured by generations of Middleton descendants, we were disappointed by the no interior photos policy. These interior images are from the Middleton Place website.

In about 1741 Henry Middleton began to lay out the famous gardens that surround the plantation house. For about 10 years 100 slaves are said to have labored to complete the 45-acre garden and 16-acre lawn. It was the most ambitious landscaping project then ever seen in the Americas.

Terraces and butterfly ponds

Entry road

The Middleton Oak

The gardens, reflect the grand classic style that remained in vogue in Europe and England into the early part of the 18th century. Henry’s design followed the principles spelled out by André Le Nôtre, the master of classical garden design who laid out the gardens at the Palace of Versailles. Rational order, geometry and balance; vistas, focal points and surprises were all part of the plan.

An elegant terraced lawn drops down in stages to unique butterfly ponds set in the river, walkways and allées are lined with trees and shrubs, hedges partition off small galleries. Arbors and sculpture are placed at the end of long vistas. The gardens today represent the evolution by subsequent generations making additions over time.

The gardens are known for a year-round display of blooms. We were there in July so we missed the azaleas but caught the hydrangeas. Apparently November through March are exceptional because of the camellias showing off throughout the garden: winter’s rose – camellia japonica or camellia sasanqua – blooms at every turn.

Sidney Frazier, VP of Horticulture, trims camellias

Azaleas in bloom by the Rice Mill Pond

Crepe myrtles overlook the Reflecting Pond

Arthur Middleton befriended the French botanist, André Michaux, who is thought to have brought the first camellias in America to Middleton Place. Arthur’s son planted many more camellias and introduced additional plant material, including tea olives and crepe myrtles. Williams Middleton expanded the Gardens, bringing in azaleas – of which there are now more than 100,000! In the early 20th century, the wife of Middleton descendant J.J. Pringle Smith restored the landscape that had been largely neglected for nearly six decades following the Civil War. Her efforts led the Garden Club of America to describe Middleton Place in 1940 as the “most important and interesting garden in America.”

We were short on time, so we missed seeing the Stableyard and Eliza’s House, two other historically important features of Middleton Place:.

It is a central tenet of the Foundation’s mission that it should be telling the story not just of the plantation’s white owners, but also its African and African American population. At the Stableyards, living historians keep the past alive as they demonstrate the skills employed by slaves, like candle-dipping, pottery making, carpentry, and keeping the horses shoed. Heritage breeds include Belgian draft horses, sheep, goats, and hogs.

Eliza’s House is a Reconstruction-era freedman’s dwelling with a permanent exhibit on slavery entitled Beyond the Fields. Based on extensive research over the course of a decade, the exhibit documents the story of slavery, in South Carolina and at Middleton Place. The focal point of the exhibit is a panel with the names of over 2800 African and African American men, women and children enslaved by the Middletons. Named for its last resident, Eliza Leach, the building opened as a house museum for visitors in 1991.

A visit to Middleton Place is highly recommended!

Hmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a little trip …

Middleton Place

4300 Ashley River Road, Charleston, SC 29414

843-556-6020

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the only search engine that makes it easy to discover 1800 art museums, historic houses & artist studios, and sculpture & botanical gardens across the US.

Just go to ArtGeek.art and enter the name of a city or state to see a comprehensive interactive listing of museums in the area. All in one place: descriptions, locations and links.

Use ArtGeek to plan trips and to discover hidden gem museums wherever you are or wherever you go in the US. It’s free, and it’s easy and fun to use!

© Arts Advantage Publishing, 2024

Thanks! Next trip to Charleston, I hope to explore the plantations. Your article helps shape my itinerary