Each time we mentioned that we were going to Houston for a few days, we were asked “Do you have family or friends there?” Hearing that we don’t, the inevitable ensuing question “So why are you going?” conveyed real perplexity as to what other reason there could be to go to Houston!

“You’re going to Houston for art?” The idea isn’t as incredible as it might seem. Wherever there’s been an accumulation of wealth – like oil money – there’s usually a pretty good art museum.

In fact, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH) is way more than “pretty good”. I’d say it fits in the “world class” category, in large part because of Gary Tinterow – a native Houstonian – who has been Director since 2012.

Tinterow returned to Houston after a three-decade curatorial career at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Under his watch the facilities have been renovated and expanded so that the MFAH is now the 12th largest art museum in the world, in terms of square feet of gallery space.

Entrance to the Law Building

Aerial view of the new Kinder Building

Photo credit: Peter Molick / Thos. Kirk III

The permanent collection spans more than 6,000 years of history with approximately 70,000 works from six continents.

The MFAH now encompasses a 14-acre campus with seven buildings and a sculpture garden, plus two off-site house museums, Bayou Bend and Rienzi. The main public collections and exhibitions are at the center of the campus in the Law, Beck, and Kinder buildings, which sit kitty-corner to each other at the intersection of Main and Bissonet Streets. They are connected underground via must-see art-imbued tunnels.

Installation at intersection of tunnels

Arts of the Pacific

Tunnel between Beck and Kindle buildings

Carlos Cruz-Diez, Chromosaturation MFAH, 2020

Enlarging a venerable old city museum can be a real challenge. The original neo-classical building (1924) had an imposing entrance facing across a manicured lawn to three billowing fountains, but over time that refined mood has been lost as buildings proliferated and the original façade became the back of the Law Building. Our Uber dropped us off near the intersection and we were unsure of which building to go to – in part because the directional signs didn’t have the sort of presence one would expect of a major museum: more like the signage you’d see at a car show or equestrian event. At the time of our visit, the arrows led us from the unsigned, locked front entrance of the Law Building, across the street, and through a porte-cochere that effectively obscured the entrance to the Beck Building.

Original museum entrance

View from original entrance

Museum entrance today

But — once inside, uncertainty dissipated. With a map in hand, the complex becomes easy to navigate.

And — once inside, the pleasure begins. The two-story light-filled atrium in the Beck building holds a small but exemplary display of Greek, Egyptian and Roman antiquities. While these spaces serve as the route to the American and European galleries, they are not easy to rush through!

Gallery view, 1st floor

Ibis, Egyptian, 664-332 BC, wood & bronze

Roman sarcophagus, 140-170, marble

Roman mosaic, Apollo & Marsyas

2nd-3rd C, stone & glass

Gallery view, 2nd floor

American Art

The American Galleries on the ground level are a delight, presenting surprises as well as “comfort-food” among paintings, sculpture, photography, books, prints, furniture, ceramics, metals, textiles and costume. Created by artists across 250 years of our history, hundreds of artworks convey temporal ideas about the American experience of religion, national identity, nature, war, fashion, achievement and more.

Gallery view

Buffalo Kachina, c.1915

E. Martin Hennings, Passing By, c.1924

Anna Hyatt Huntington, Red Deer, 1929, bronze

Parlor Cabinet, c.1862 Marquetry attributed to Joseph Cremer

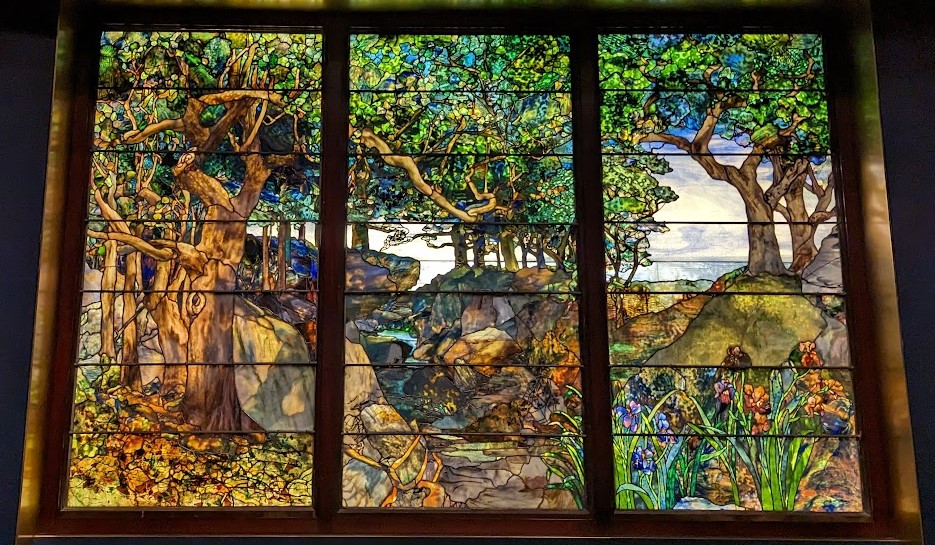

Louis Comfort Tiffany, A Wooded Landscape in Three Panels, c.1905

The collection of John Singer Sargent, William Merritt Chase and other American artists of their generation is superb. Two favorite Sargents:

Mme. Ramon Subercaseaux, c. 1880

Young Man in Reverie, 1878

It’s always a treat to encounter a painting that stops me in my tracks, especially when it’s by an artist previously unknown to me. In this case, it was Duck Hunting, painted in 1867 by Jerome B. Thompson. Interestingly, Thompson’s father — himself a distinguished portrait painter — refused to give his son art lessons, and even destroyed some of the boy’s early paintings because he wanted him to become a farmer. Happily, Jerome ignored his father’s wishes and went on to produce work like this:

Jerome B. Thompson, Duck Hunting

Duck Hunting, detail

We happened to move through the American galleries in reverse chronological order, so rounding out our peregrination there was a surprising early Albert Bierstadt, a familiar Raphaelle Peale, a number of Benjamin West paintings, and various Colonial artifacts, including a charming 18th-century wooden sewing box.

Albert Bierstadt, A Rustic Mill, 1855

Raphaelle Peale, Orange and Book, c.1817

Unknown Mexican, Sewing Box, c.1780

European Art

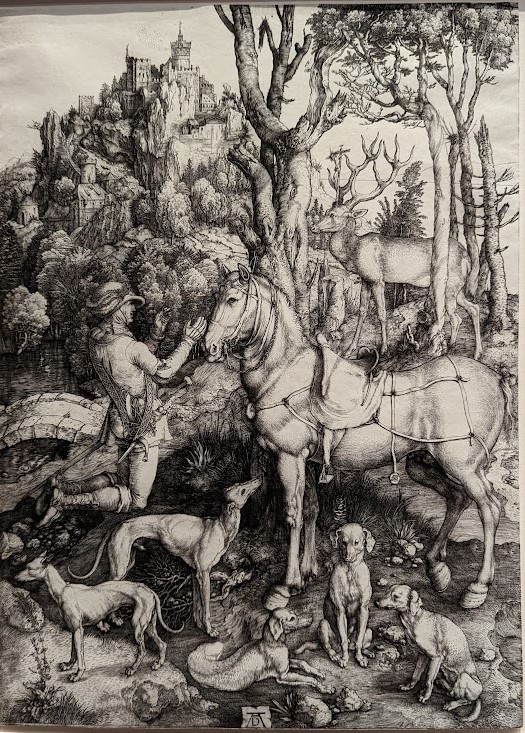

Following on the heels of the high-caliber American collection, the European collection did not disappoint. Starting with a fabulous cabinet of curiosities (which will soon have it’s own blog post), we were delighted by one stunning work after another, room after room, from Medieval to Modernist. Virtually every renowned artist in the history of European art is represented, from Botticelli to Bonnard, Memling to Munch, Dürer to Degas.

Cabinet of Curiosities

Medieval gallery

Impressionist gallery

Sandro Botticelli, Portrait of a Young Woman, c.1485-90

PIerre Bonnard, Dressing Table and Mirror, 1913

Hans Memling, Portrait of an Old Woman,

1468-70

Edvard Munch, Garden in Taarbaek, 1905

Albrecht Dürer, Saint Eustace, c.1500-01

Edgar Degas, Russian Dancers, c.1899

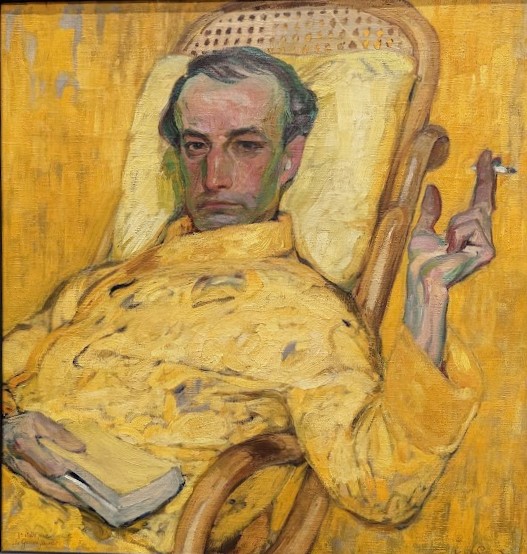

There was a roomful of Fauves, screaming with color. This group of young painters, including Matisse and Derain, “exploded onto the Paris art scene at the Salon d’automne in 1905, where, in contrast to the Renaissance-style sculptures displayed in their midst, they seemed like fauves (wild beasts)” to one prominent art critic. The movement itself was short-lived, but the name stuck and the use of intense coloration was here to stay.

Andrre Derain, The Turning Road, L’Estaque, 1906

Frantisek Kupka, The Yellow Scale, c.1907

Henri Matisse, Woman in a Purple Coat, 1937

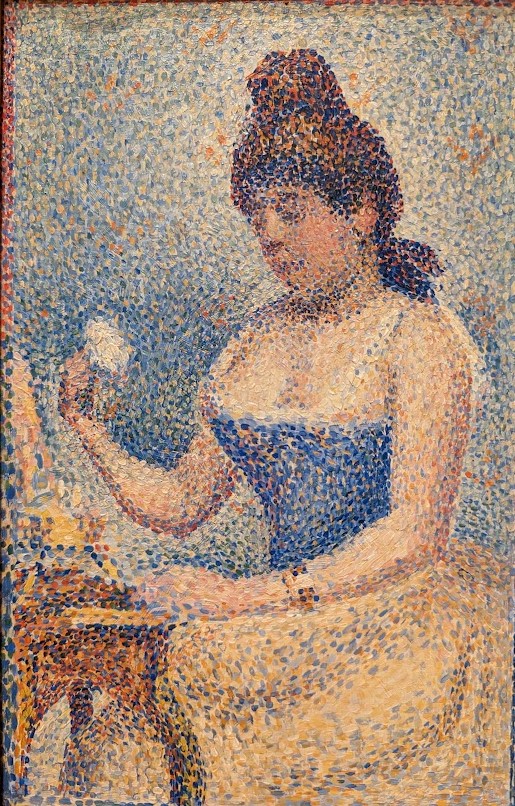

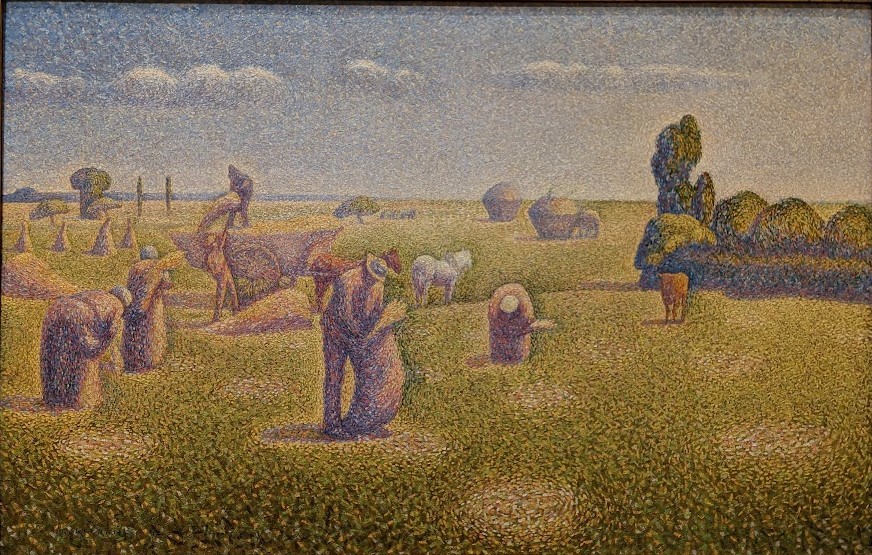

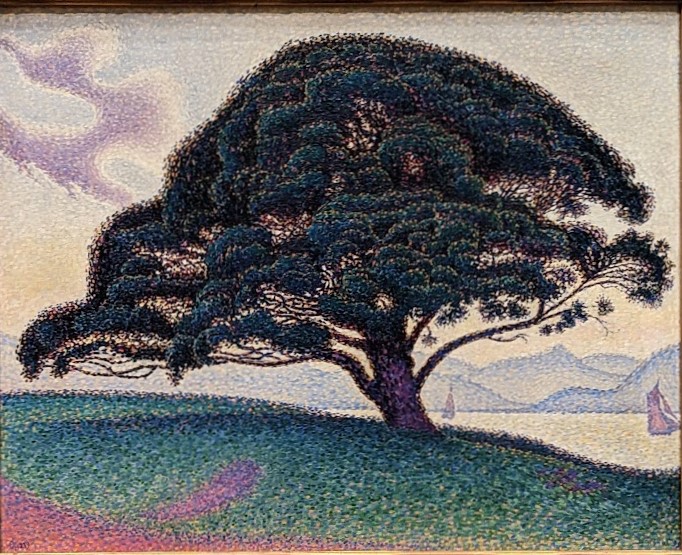

Then there was the Pointillist room, shimmering with a million tiny dots, each work painted in “a quest for a more rigorous interpretation of Impressionism’s light and color.”

Georges Seurat, Young Woman Powdering Herself, 1889

Charles Angrand, The Harvesters, 1892

Paul Signac, The Bonaventure Pine, 1893

Close looking was rewarded time after time. A couple of favorites were Michele Marieschi’s c. 1740 View of the Dogana and S. Maria della Salute, Venice, and Claude Lorrain’s Landscape with a Rock Arch and River, which he painted c.1628-30.

Michele Marieschi, View of the Dogana and S. Maria della Salute, Venice, c.1740

Marieschi, View, detail

Lorrain, Landscape, detail

Claude Lorrain, Landscape with a Rock Arch and River, c. 1628-30

What Else?

We hadn’t allowed enough time to see anything close to the entire museum, and at this stage in our visit, we’d only covered the two floors of the Beck Building! We didn’t make it to the Law Building at all, where the arts of Africa, Asia, the Pacific, the Islamic world, and the indigenous arts of the Americas are displayed. And we only managed to take in the first floor — and a nice lunch — at the Kinder Building, with its modern and contemporary galleries.

Kinder Building foyer with Alexander Calder’s International Mobile, 1949

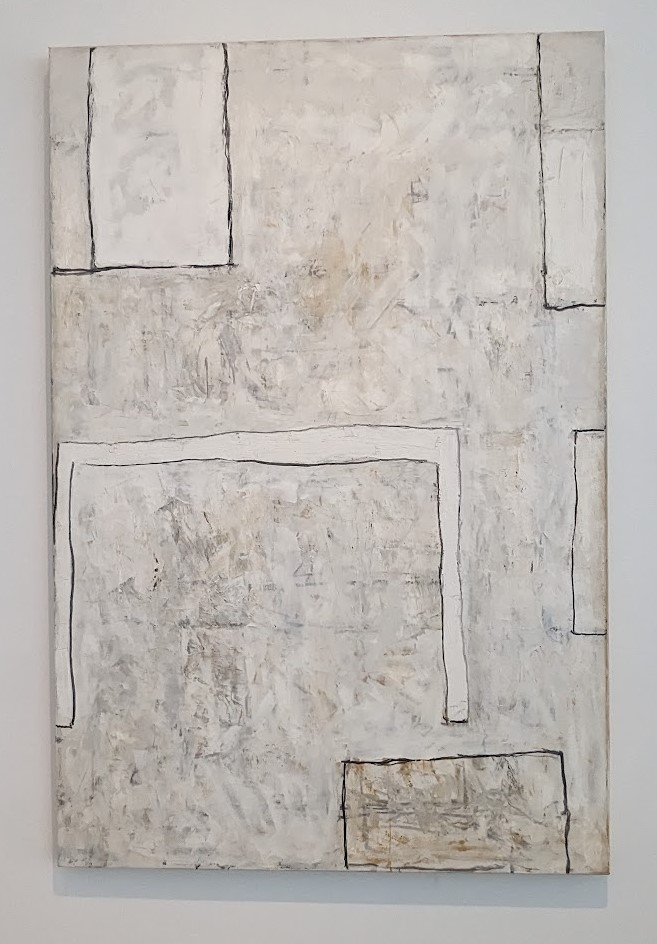

William Scott, May 1, 1961, 1961

Pablo Picasso, Woman with a Large Hat, 1962

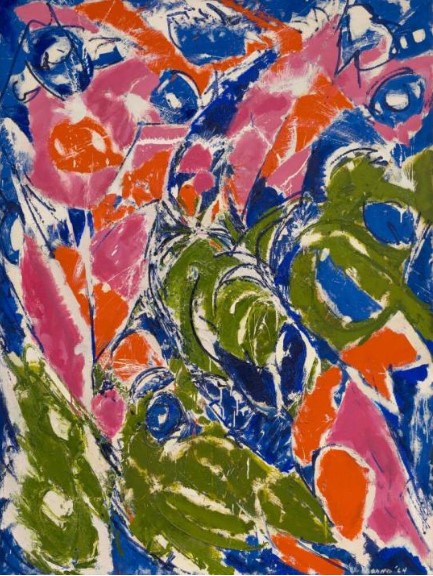

Lee Krasner, Bird’s Parasol, 1964

Anthony Caro, Orangerie, 1969

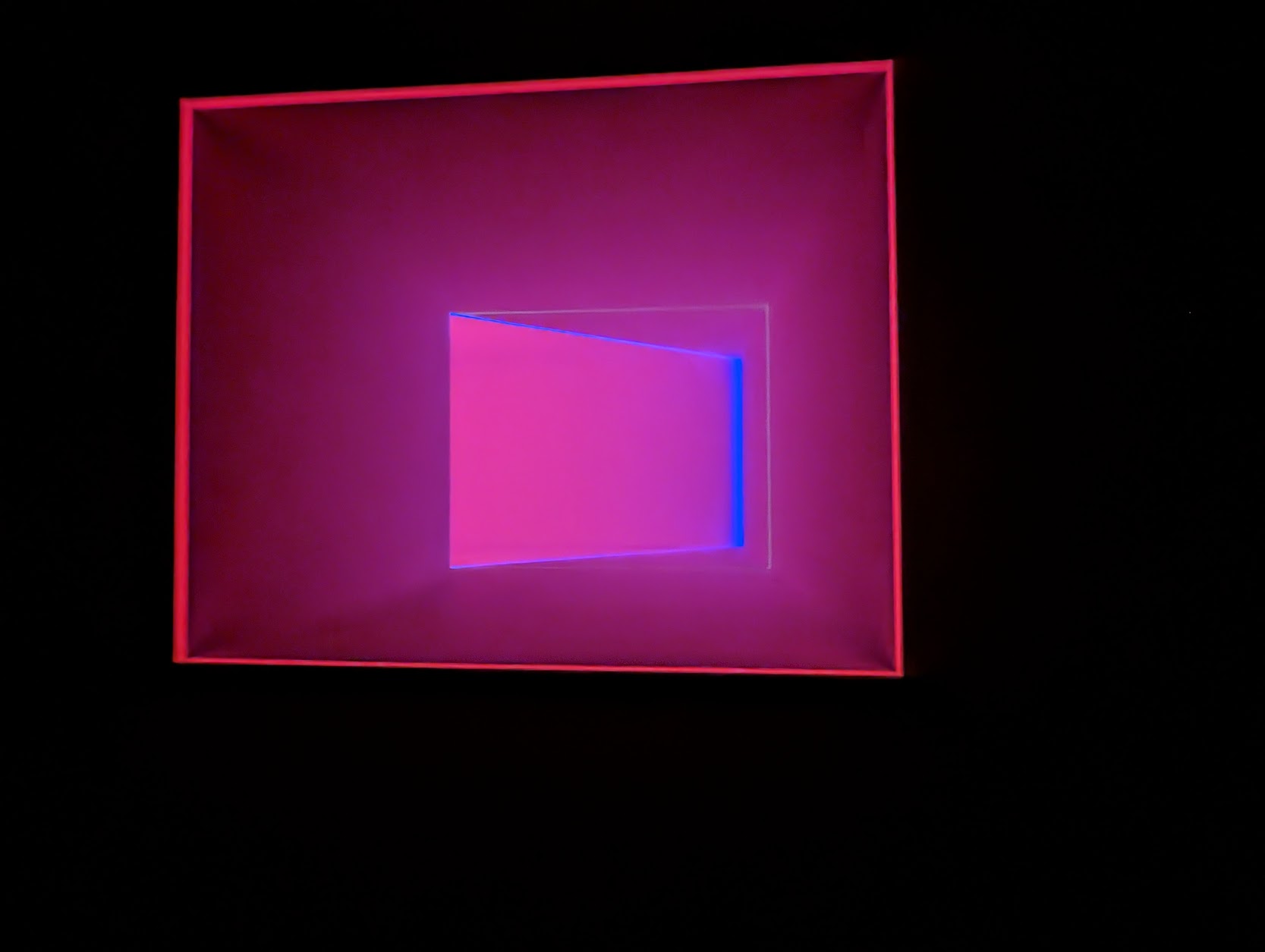

I’ve wanted to experience a Yayoi Kusama Infinity Room for a long time and it finally happened. Twice before I’ve come close, but both times they were closed due to Covid, so this was a bucket list treat. All you get is a minute, but all it takes is a minute to grasp the infinite extent of mirrored replication. Then, to wrap up our time in the MFAH, we had a short stint sitting quietly in the viewing room of James Turrell’s subtly-changing LED and flourescent-light Caper, Salmon to White: Wedgework .

Yayoi Kusama, Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity, 2009

James Turrell, Caper, Salmon to White: Wedgework, 2000

A final few minutes were spent wandering in the Cullen Sculpture Garden, adjacent to the Kinder Building, while we called for an Uber pick-up. The small urban garden, dotted with both figurative and abstract sculptures, is surprisingly peaceful given it’s proximity to a busy intersection.

Marino Marini, The Pilgrim (Il Pellegrino), 1939

Anish Kapoor, Cloud Column, 1998–2006 (Art School behind)

Aristide Maillol, La Rivière (The River), 1938–1943

Had we been aware of the sheer magnitude and magnificence of MFAH holdings, we would have built time for a second visit into our schedule. Looks like a return visit to Houston is in our future!

Hmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a little trip …

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

1001 Bissonnet, Houston, TX

713-639-7300

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the only search engine that makes it easy to discover almost 1700 art museums, historic houses & artist studios, and sculpture & botanical gardens across the US.

Just go to ArtGeek.art and enter the name of a city or state to see a complete interactive catalog of museums in the area. All in one place: descriptions, locations and links.

Use ArtGeek to plan trips and to discover hidden gem museums wherever you are or wherever you go in the US. It’s free, it’s easy to use, and it’s fun!

© Arts Advantage Publishing, 2023