Seeing an array of Félix Vallotton’s work — as we did on opening day of the exhibition Félix Vallotton: Painter of Disquiet – made us wonder why we were not more familiar with him. In darkly suggestive paintings and graphically spare prints, he chronicled fin de siècle Paris like no other artist of his generation.

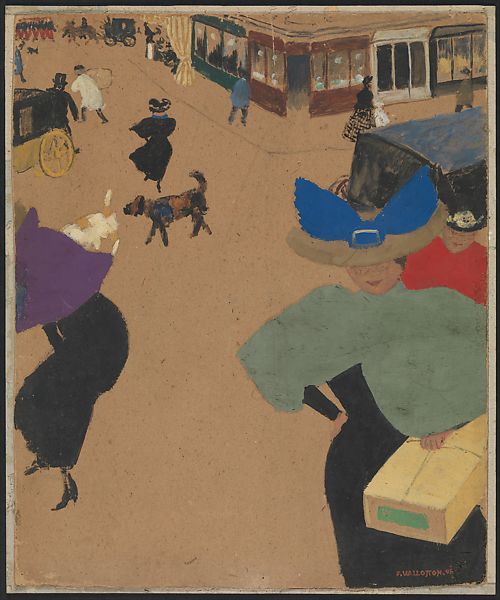

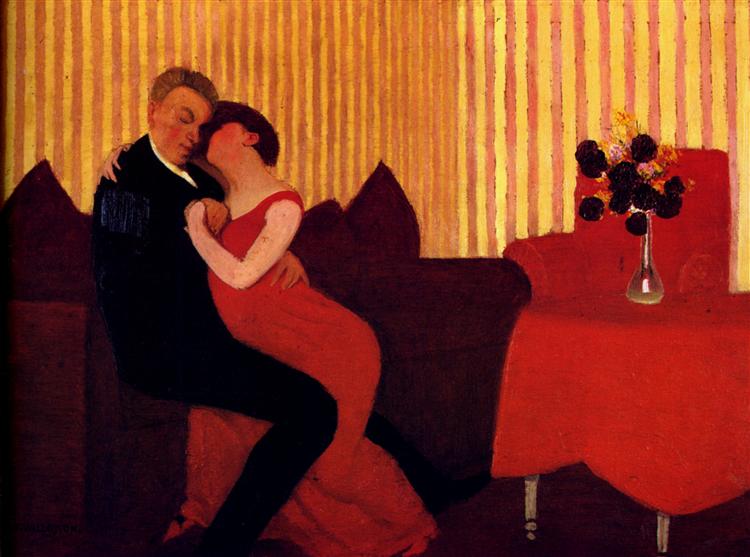

Gouache & oil on cardboard. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Félix Edouard Vallotton (1865–1925) was a highly original artist whose diverse talents have never been fully recognized. In the first U.S. exhibition of his work in nearly 30 years, The Metropolitan Museum of Art profiles his career as a painter and printmaker through some 80 works of art from more than two dozen lenders (on through Jan 26, 2020). His Early Modernist paintings and prints include startingly realistic portraits, mysterious interiors, luscious still lifes and brooding landscapes.

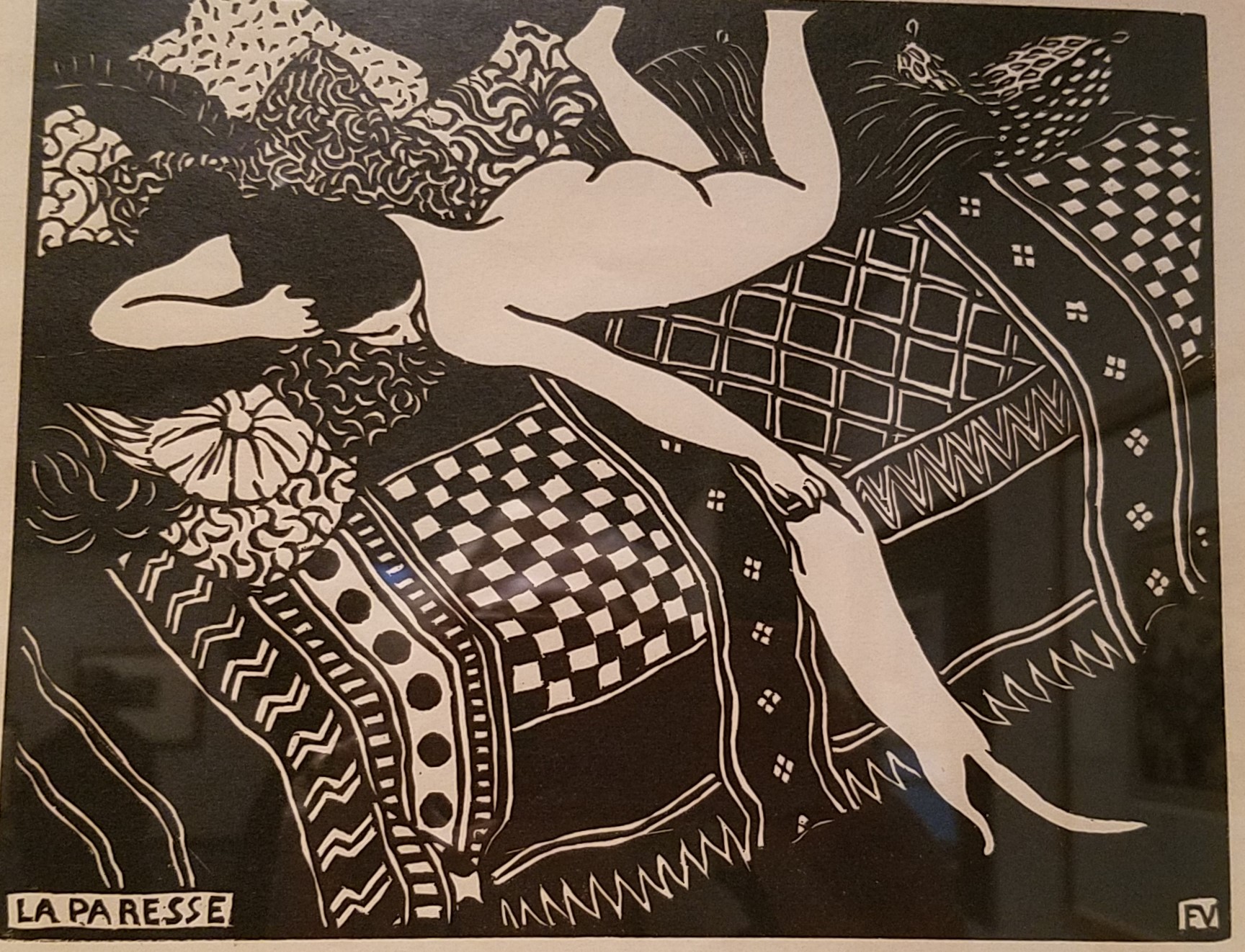

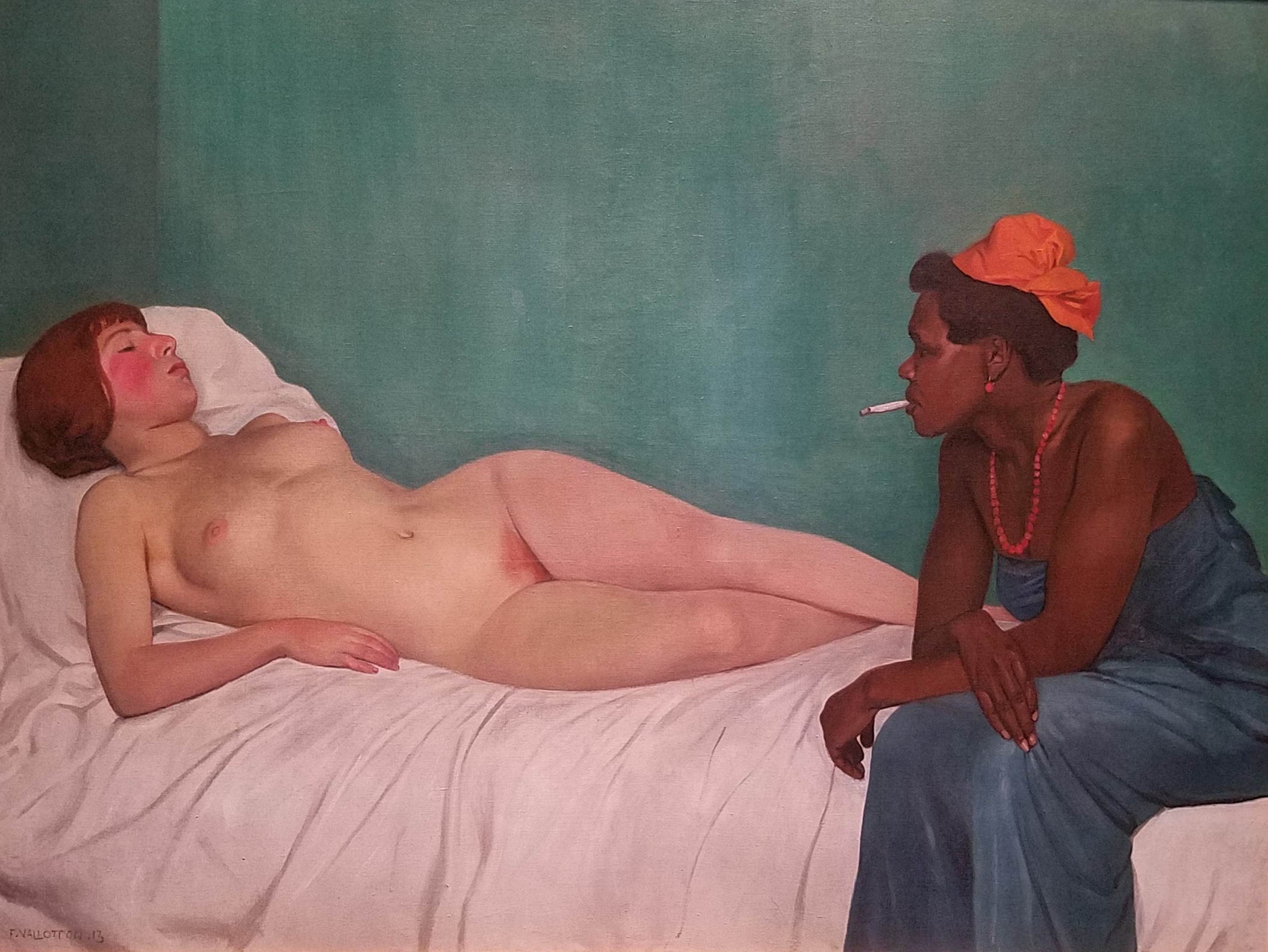

Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne

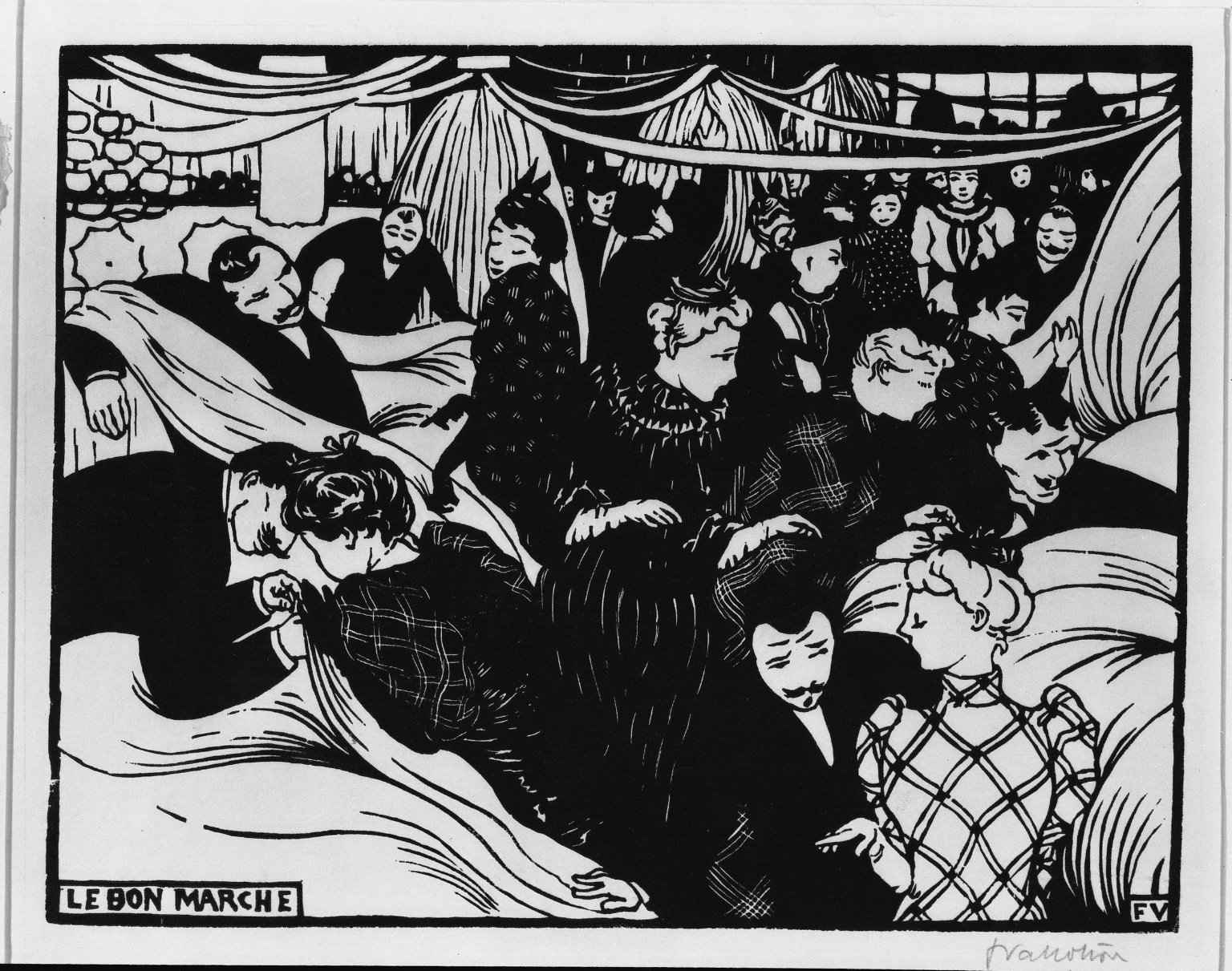

Vallotton was a keen observer of urban life, and his illustrations were published frequently in literary magazines and left-wing journals through the 1890s. The incisive wit of the woodcuts he executed in Paris in the 1890s built him a solid reputation in the graphic arts.

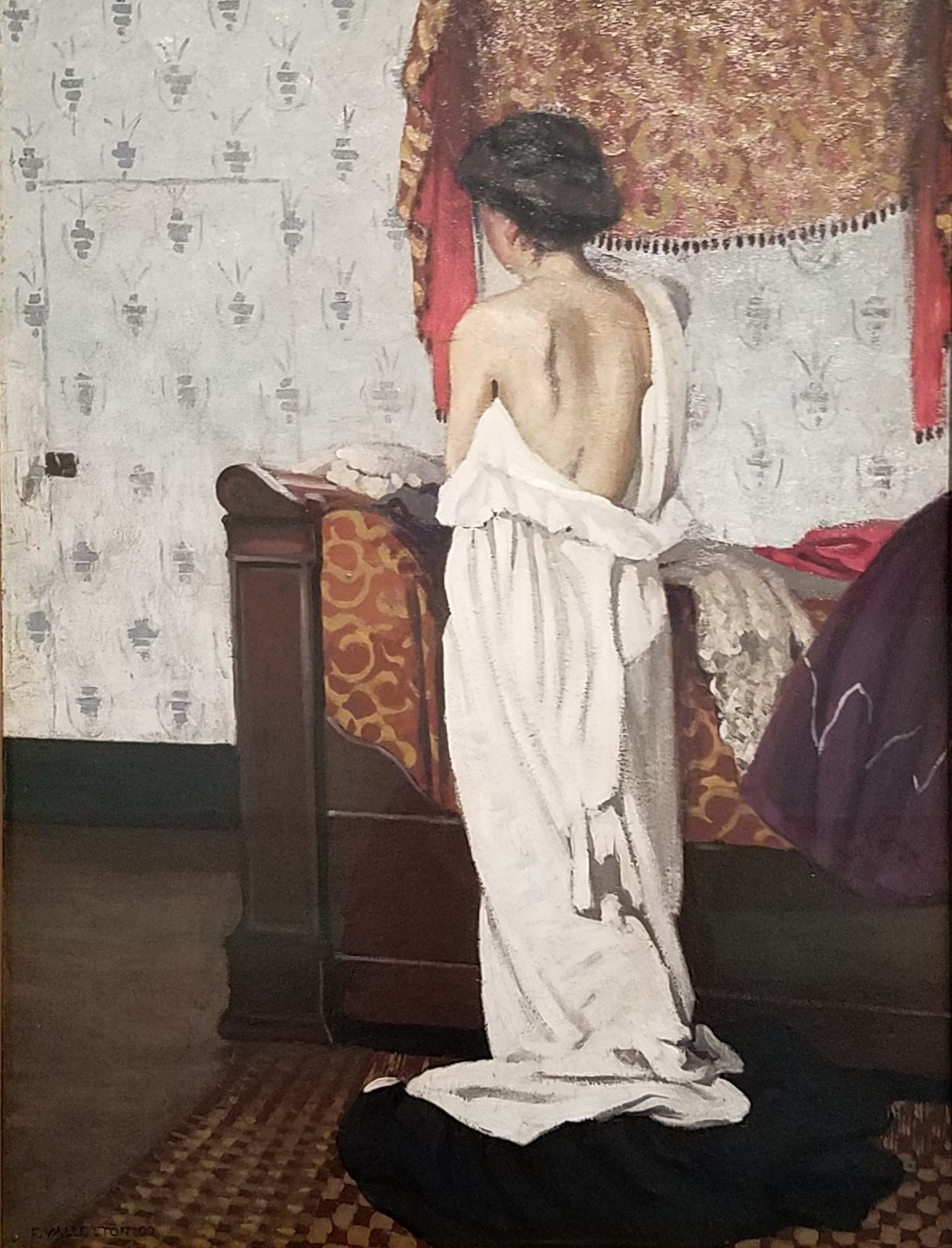

Musée cantonale des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

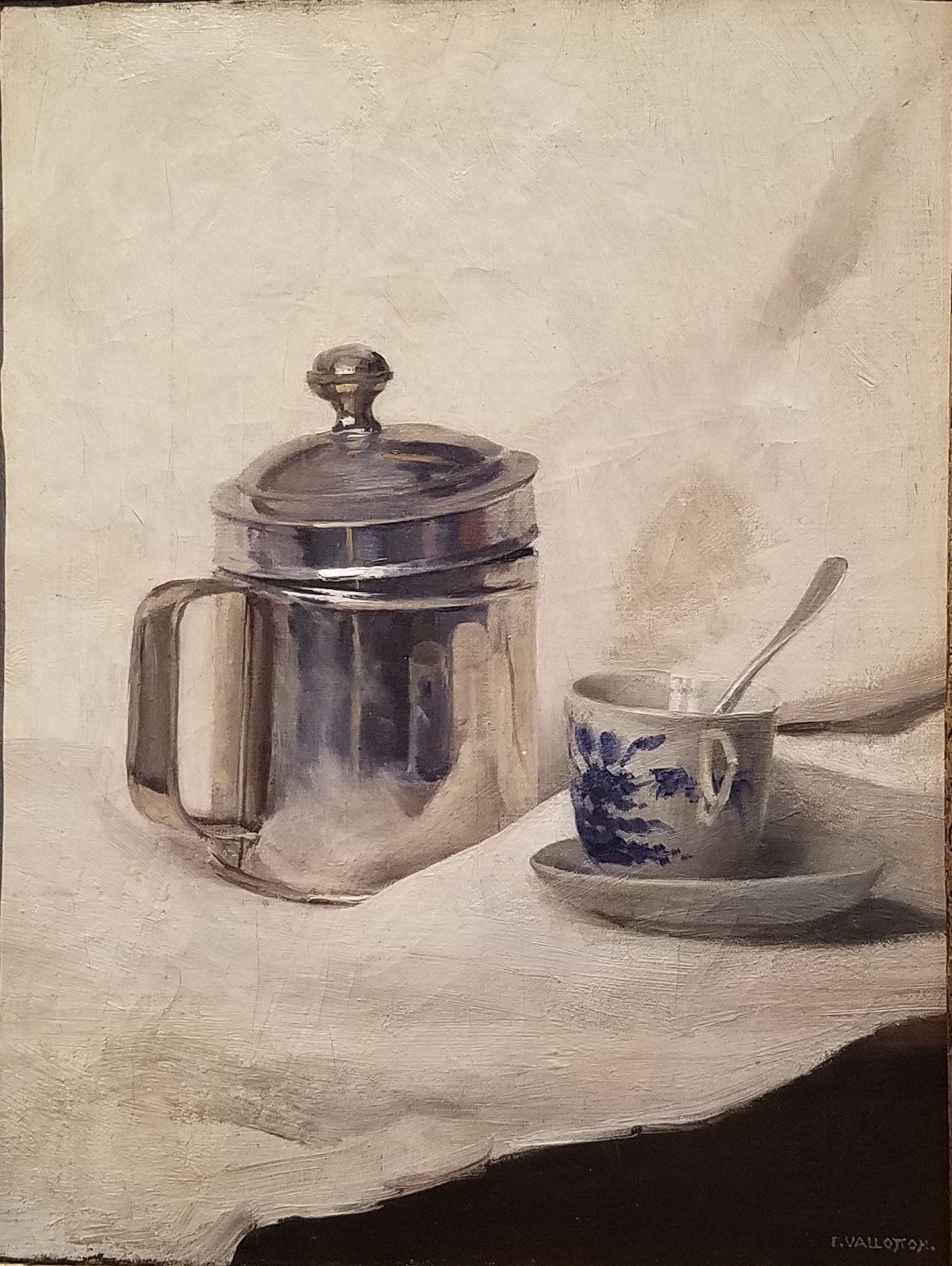

Vallotton left Lausanne for Paris at the age of 16 and studied at the Académie Julian, where he trained under the painters Jules Lefèbvre and Gustave Boulanger. His early paintings reveal a precocious talent, and the influence of the Northern European realist tradition.

Oil on canvas, Private collection

He was born into a Swiss Protestant family (think Calvinism), instilled with the esteemed self-disciplines of precision (think Swiss watches), punctuality (Swiss trains) and thriftiness (Swiss banks). Those qualities set him apart as a young artist in Paris, and informed his work throughout his career.

The 1890s was a time of transition in France that saw increasing tensions between the bourgeois establishment and social reformers, and Vallotton was engaged with the political atmosphere. But we’ve found nothing to suggest that he was anything beyond sympathetic to the political protesters – including his friend, anarchist and art critic Félix Fénéon, who was accused of a bombing and tried for his anarchist beliefs in 1894.

Although he was intensely critical of the values of the Paris upper class, it seems Vallotton gave expression to his political views entirely through ironic artistic statements.

The curators of the exhibition make much of Vallotton’s revolutionary tendencies. We understand the drive to try to enhance the relevance of the exhibition to a present-day audience, but to interpret his work through the lens of today’s politically-charged attitudes may distort understanding of the historical reality of Vallotton’s world, and overstate the extent of his anarchic proclivities.

Vallotton found by skillfully manipulating the high contrast of black and white the relief-printmaking process of woodcut was a particularly powerful medium to illustrate political and satirical tension in his works, even in small-scale images. His work may have been inspired by real-life demonstrations, but despite the obvious political nature of these scenes, the artist’s stance on the action represented often remains ambiguous.

While creating illustrations for the avant-garde journal La Revue blanche, he met members of the Nabis circle, Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard in particular. (The name Nabis was derived from the Arabic for “prophet”). Stylistic revolutionaries, the Nabis took inspiration from the Post-Impressionist style of Paul Gauguin, and popular Japanese woodblock prints. Forswearing illusions of depth and three-dimensionality, they abandoned linear perspective and modeling.

Vallotton’s art of the mid-1890s aligned with their decorative patterning, informal technique, and extreme color contrasts, as he had already begun producing wood cuts inspired by the flat colors and silhouetted forms of Japanese ukiyo-e prints. The sharp, precise contrasts that he’d developed in his print-making informed his Nabist painting technique.

This Swiss artist was a perplexing and anomalous player in Parisian art circles, referred to as le nabi étranger (the foreign Nabi). “Enigmatic” is a word repeatedly used to describe his work throughout his career.

A highlight of the show is Vallotton’s celebrated woodcuts series of shadowy interior scenes, Les intimités. Published in the journal La Revue blanche in 1898, they explore the subtle power dynamics between romantic partners and the hypocrisies of bourgeois life. With simple line and black silhouette, these spare, unsettling narratives are rife with lies, deceit, subterfuge – and ambiguity.

“I think I paint for people who are level-headed but who have an unspoken vice deep inside them.”

– Félix Vallotton

He followed this provocative print series with several paintings exploring the same themes.

The Cone Collection, The Baltimore Museum of Art, Maryland

He frequently painted intimate scenes of interactions between men and women, sometimes in restaurants, sometimes at the theater — often suggesting seduction or coercion, rarely suggesting romance or love.

“He only enjoys bitterness” (“Il ne se régale que d’amertume.”)

– Jules Renard, referring to Vallotton’s morbid delight in observing life’s harsh realities

When asked what underlies the ambiguous narratives of Vallotton’s art, Ann Dumas, who conceived and curated the exhibition, says, “I think enigma is what it’s about. It’s always a man and a woman interacting in a more than slightly claustrophobic, bourgeoise interior,” she explains. “You never quite know what the relationship is, what the transaction is. You always get the sense it is some kind of illicit relationship.”

Kunstmuseum Bern, Villa Flora, Winterthur, Switzerland

While he had overtly satirized the French bourgeoisie, Vallotton married into their ranks in 1899, joining the famed Bernheim-Jeune family of art dealers. Marriage to Gabrielle Rodriques-Enriques brought financial security and meant an end to printmaking as an essential source of revenue. Thereafter, Vallotton devoted himself exclusively to painting, dividing his time between winters in Paris and summers in Normandy with Gabrielle and her family.

He cultivated a unique manner of storytelling – balancing figurative realism with threateningly amorphous shadow.

Oil on cardboard mounted on wood. Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Summering in the Normandy countryside led him to paint more landscapes. With a recently-invented Kodak camera in hand, he took snapshots of scenery that appealed to him, or he sketched on-site, and then composed paintings in his studio, calling them paysages composées. He simplified his compositions into zones of color — reminiscent of his earlier woodcuts — creating abstractions of nature.

Oil on canvas. Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France

Subversive wit largely disappeared from his work after 1900. According to the exhibition wall text, “The female nude became Vallotton’s primary subject. (…) Ever the detached observer, Vallotton relied on a single sketch of his model drawn from life, and then in the studio he painted his subject with impeccable contours and flawless surfaces.”

Kunsthalle Bremen, Der Kunstverein, Bremen, Germany

“Visitors may be surprised,” Dumas says of the show, “by how much he changes over time.” As he matures, “he becomes obsessed with the French neo-classical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and develops this cold hard-edged realism.”

The exhibition includes several of Vallotton’s arresting portraits, including two self-portraits and a charming 3/4-length view of his wife, Gabrielle.

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux, France

His portrait of the American expat collector and writer, Gertrude Stein, depicts her as massively solid and emotionless. It was painted one year after Pablo Picasso made his portrait of her, and the two are displayed here side-by-side. Stein disliked the picture and dimissed Vallotton in her autobiography as “a Manet for the impecunious.” This seems a tad nasty and supercilious, since apparently the artist gave her the portrait as a gift! (It is said that she didn’t like Picasso’s rendering either.)

Left: Pablo Picasso. 1905-06. Metropolitan Museum, New York NY

Right: Félix Vallotton, 1907. Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore MD

Vallotton flourished in the atmosphere of social instability and free-wheeling creativity that characterized Paris at the turn-of-the-century. This exhibition explores the trajectory of his career, revealing numerous changes in his artistic style, subject matter, and the medium in which he worked.

“His was a singular vision, pursued with singular determination for a lifetime.”

Hmmm … maybe it’s time to plan a little trip?

Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue, New York City, NY

212-535-7710

Feature image: Félix Vallotton, Self-Portrait, 1897 (age 32). Oil on Board

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the search engine to easily find more than 1300 art museums, historic houses and artist studios, and gardens across the US.