For people who lived (and died) in the 14th century — when the Great Plague (aka the Black Death, the Great Mortality) killed roughly half the world’s population — a truly horrible death was not hard to envision.

Lack of sanitation, marauding armies, high infant mortality, famine, primitive (often barbaric) medical treatments, no FDA inspections of food, no OSHA regulation at the job site … it’s almost impossible for most of us, today, to understand the constant presence of death that was the reality of life for everyone until very recent times. (Our great good fortune in this respect accounts for why the sudden onslaught of the coronavirus pandemic came as such a shock.)

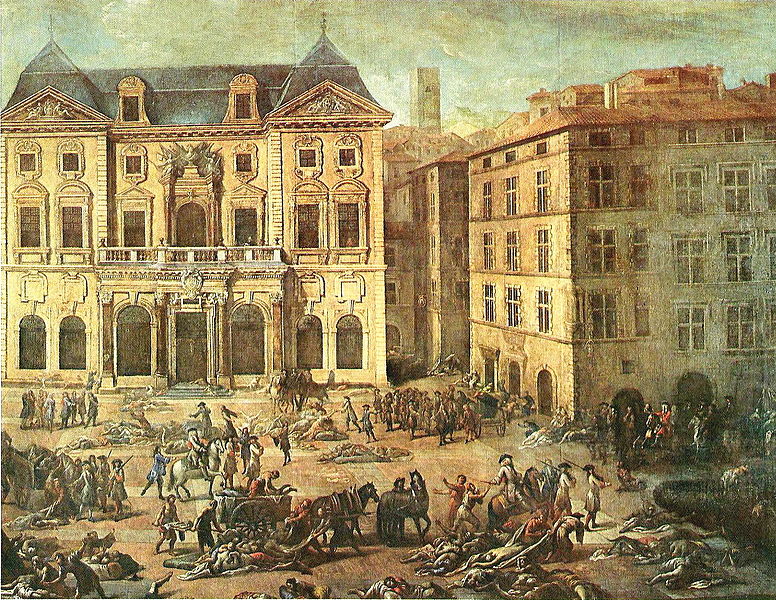

It is estimated that in Mediterranean Europe the plague wiped out 75-80% of the population in just four years. After that, devastating plague epidemics popped up somewhere in virtually every generation until it made its final appearance in Europe in the 19th century.

Michel Serre (1658-1733)

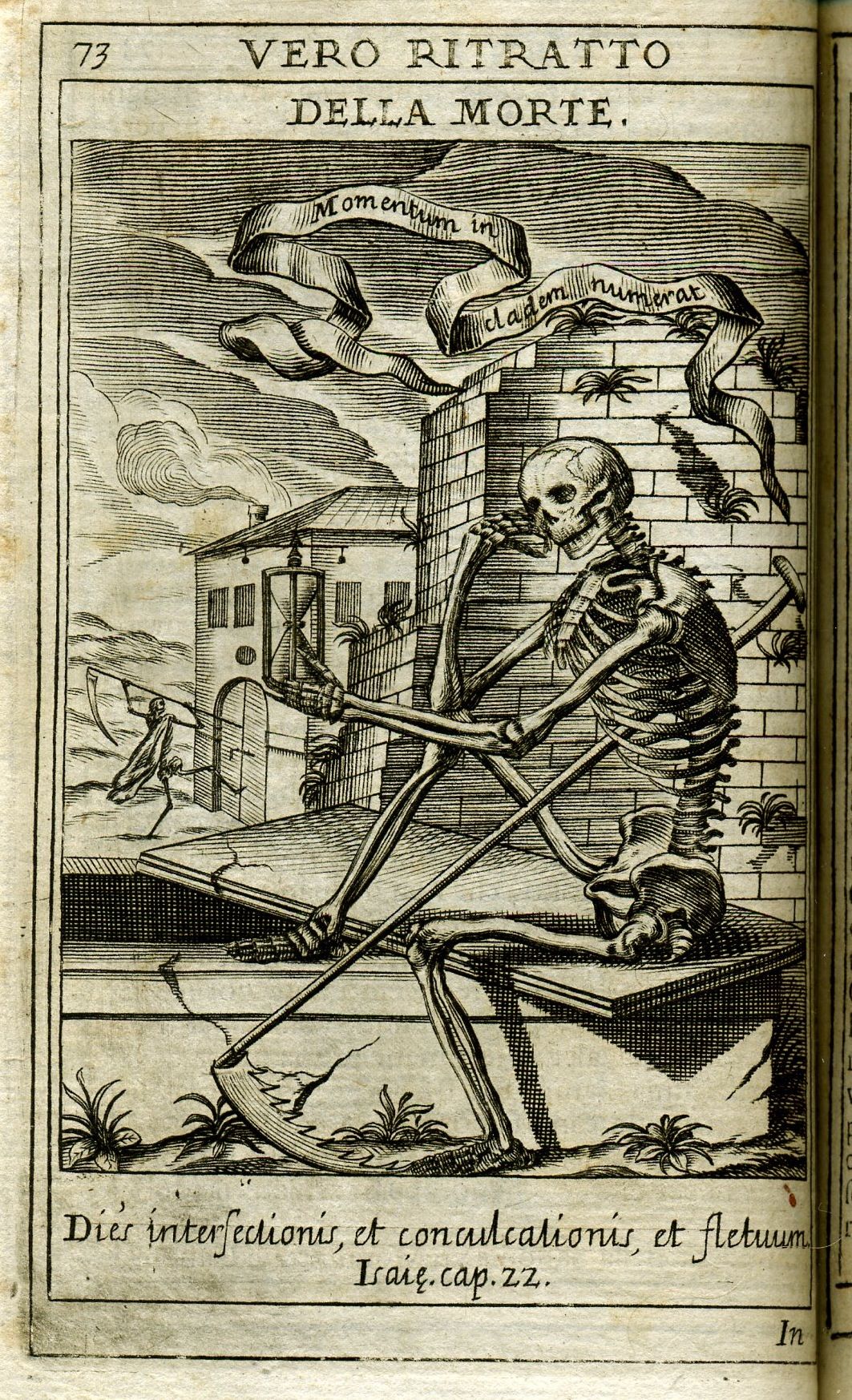

Given the uncertainty of daily survival, one of the most widely circulated books printed with movable type before 1500 was a self-help book called Ars moriendi (The Art of Dying). Written in the context of the horrors of the Black Death, it provided protocols and procedures for how to “die well” according to Christian precepts of the late Middle Ages.

Prior to the Great Plague, the rituals and consolations of the deathbed were generally attended to by a clergyman. But the priesthood had been especially hard hit by the pandemic, and it would take generations to rebuild. Ars moriendi was an innovative response by the Church to provide the guidance of a “virtual priest” to those who sought to die with propriety.

Gradually, the idea of preparing for one’s own death became common practice, as a daily meditation, during bad times — and good. We know, for example, that the 17th century sculptor, Gian-Lorenzo Bernini, was a devout practitioner of the art of dying well. The contemplation of death, in itself, could become the art of living well.

Chigi Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome

(Listen to a short audio clip on The Art of Dying related to the above image.)

As it always does, art reflected the times, and a type of art – the memento mori – came into being, to emphasize the fleeting nature of earthly pleasures and achievements, and to focus meditation on the prospect of the afterlife. “Memento mori” is a Latin phrase which translates as “Remember your mortality” or “Remember you will die.”

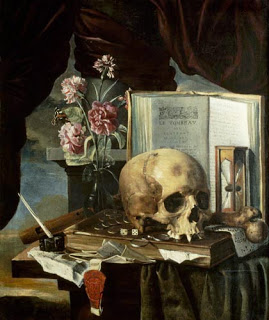

Related to memento mori, a vanitas painting is a still-life containing symbols of death, meant as a reminder of the transience of life, the vanity of ambition, and the ephemeral nature of earthly pleasures. In reminding the viewer of inevitable death, a vanitas painting serves as a veiled exhortation to repent.

Vanitas Still-Life. Oil on canvas. Private collection

Common vanitas symbols include human skulls, over-ripe fruit and decaying flowers, smoke, time-pieces, bubbles, musical instruments, and jewelry, gold and other riches.

Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

I suspect that some artist took pleasure in the fact that a sensuously-rendered vanitas still life could evoke a pleasurable viewing experience that was in direct conflict with the moralistic message! And, ironically, while these paintings were intended as an admonition against wordly pleasures, they were themselves costly luxury items that only the wealthy could afford.

The contemplation of death doesn’t place high in our modern range of favorite diversions. In fact, the very idea seems in opposition to today’s injunction to “live in the moment,” to maintain an open and intentional focus on the present.

Nonetheless, we can be in the moment, practicing the art of now, and understand so-called vanitas pictures in the historical context of what they meant to generations of humanity. And in so doing, we can better appreciate their inherent beauty.

Feature image: Pieter Claesz, Still Life with Violin and Glass Ball, 1628. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg

Art Things Considered is an art and travel blog for art geeks, brought to you by ArtGeek.art — the search engine that makes it easy to discover more than 1300 art museums, historic houses & artist studios, and sculpture & botanical gardens across the US. Just enter the name of a city or state to see a complete catalog of museums in the area. All in one place: descriptions, locations and links.

Thank you.

My pleasure. Glad you liked the post.