T. C. Cannon bravely rejected the flat representation of Indian ritual and daily life that still pervaded native art in the 1960s, developing a color-drenched modern painting style all his own.

T.C. Cannon’s death in a car accident in 1978, when he was just 31, was a tragic loss of a soaring talent. Already gaining attention beyond the shores of his native America, he was instrumental in creating an unprecedented contemporary native art that could hold its own alongside the mainstream of American art.

A long-overdue retrospective of his work — T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America — is currently on at the National Museum of the American Indian George Gustav Heye Center in New York City (through September 16, 2019).

“I am tired of Bambi-like deer paintings reproduced over and over—and I am tired of cartoon paintings of my people.” T.C. Cannon

Born and raised in Oklahoma, (Caddo and Kiowa, 1946–1978), T.C. Cannon’s Kiowa name was “Pai-doung-u-day” (One Who Stands in the Sun). He left home in 1964 to attend the recently-opened IAIA (Institute of American Indian Arts) in Santa Fe, New Mexico. IAIA was — and still is – a progressive art school in a progressive art town.

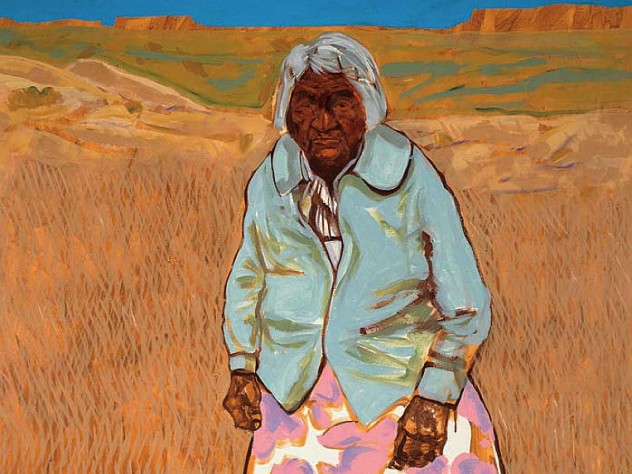

Painted by T. C. Cannon as a student in 1966. Acrylic and oil on canvas.

IAIA, Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

© 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon. Photo by Addison Doty

It was a place where promising American Indian artists were challenged to push beyond the traditional, where in the 1960s and 70s a group of young artists forged a contemporary native art form. Drawing on American and European art movements of the time they created work that was both cosmopolitan and reflected their tribal traditions. The early graduates from IAIA paved the way for decades of Native artists to come. “It was a revolution,” says Karen Kramer, curator of the exhibit and PEM’s Native American and Oceanic Art and Culture.

Cannon and his fellow art students upended tradition and vowed to show their real life instead. T.C. did not want his art to be pigeon-holed as native, nor did he want his cultural identity to define him. He was an artist, period. And a poet, singer and song-writer.

“An Indian painting is any painting that’s done by an Indian. … [but] it seems beside the point to call a painting Indian just because the artist is an Indian. … People don’t call a painting by Picasso a Spanish painting…”

T. C. Cannon

After graduating from IAIA, Cannon enrolled in the San Francisco Art Institute but stayed only two months. In the Kiowa warrior cultural tradition, he enlisted in the U.S. Army and spent a year in Vietnam in 1968, earning two Bronze Star medals for his service in the Tet Offensive as a paratrooper. He was also inducted into the Black Leggings Society, the traditional Kiowa warriors’ society.

His poetry and letters from this period reveal his conflicted feelings and the emotional effect of his experience in Vietnam.

1972 was a significant year. The National Collection of Fine Arts, now the Smithsonian American Art Museum, invited him and his former instructor Fritz Scholder to be in a two-man exhibition, Two American Painters. The show was a landmark success. Jean Aberbach, the owner-dealer of Madison Avenue’s Aberbach Gallery, purchased almost all of Cannon’s canvases off the gallery walls and signed as Cannon’s agent, representing him nationally and internationally for the remainder of his life.

Photo: Thosh Collins/National Museum of the American Indian

Although he drew and sketched prolifically, Cannon painted no more than 50 major canvases and produced just a handful of exquisite woodblock prints and linocuts before his untimely death.

Cannon’s rejection of the flat representation of native ritual and daily life that still pervaded native art in the 1960s was brave and unprecedented. He developed a vibrant color-drenched painting style that reflected the influence of Van Gogh and Matisse. Combining contemporary Western art influences with native traditions he made astute social and political statements with intelligence and wry humor.

“So many issues he was grappling with in the 1960s and ’70s—freedom of religion, ethnic identity, cultural appropriation—are still so relevant,” says curator Kramer.

Anne Aberbach and Family, © 2019 Estate of T. C. Cannon.

Photo: Thosh Collins/Courtesy of National Museum of the American Indian

He created portraits of native figures centered in American history, often incorporating the motif of the stars and stripes. His chiefs and other Native people are dressed in traditional clothing but posed with contemporary objects – umbrellas and furniture, a gramophone and even an opera libretto (Tosca). His sketchbooks, though, reveal wide-ranging interests, including drawings of cats, nudes, portraits, self-portraits, studies for larger works, as well as abstracts.

© 2017 Estate of T.C. Cannon; photo by Thosh Collins)

“What is evident in the artistry of T.C. Cannon is intelligent and emotionally resonant commentary about the cultural landscape of the times in which he lived,” says Kevin Gover (Pawnee), the director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. “Cannon was a visionary at the forefront of broadening and reshaping the boundaries of Native artistic narratives. The imagery he created was stunningly authentic and has influenced the work of many other artists, Native and non-Native alike.”

Photo by Dan Kvitka/Private collection. © 2019 Estate of T.C. Cannon

Most of Cannon’s large paintings are portraits, vividly depicting Native Americans, not as decorative stereotypes but people surviving and even flourishing in the modern world. In undiluted shades of orange, purple and electric blue, his figures have flaws — pot bellies, wide hips or skeptical expressions — and one of them slouches in a folding lawn chair.

Acrylic on canvas. Peabody Essex Museum. © 2017 Estate of T.C. Cannon. Photo by Kathy Tarantola

“I have something to say about experience that comes out of being an Indian. But it is also a lot bigger than just my race.”

T.C. Cannon

Despite the engaging brilliance of Cannon’s art, until recently its impact has gone largely unrecognized beyond art circles. This is in part because most of his paintings — of which there are only a few dozen — are held in private collections, and his work is under-represented in public museums.

This show — with nearly 90 pieces — includes 30 paintings and a 22-ft. mural, as well as writings and drawings. It has pulled back the curtain, and will surely bring T.C. Cannon the much wider recognition that his work deserves.

Abbi of Bacabi (1978). Oil on canvas. Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma. © 2019 Estate of T. C. Cannon

Photo: Courtesy of the National Museum of the American Indian

Hmmm… maybe it’s time to take a little trip?

T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America

National Museum of the American Indian – George Gustav Heye Center

New York City, NY

Through September 16, 2019