Carl Who?

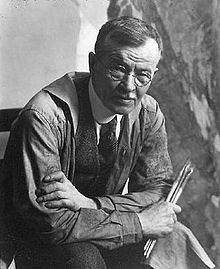

If you aren’t familiar with western wildlife art, you may not know Carl Rungius. If that’s the case, it’s my pleasure to introduce you to this ground-breaking American wildlife artist. He earned a reputation as the most important big game painter and the first career wildlife artist in North America in the early 20th century.

On a recent visit to the excellent National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, WY we became more familiar with the work and legacy of this avid sportsman, ethical hunter, outdoors-man, and superb painter of the North American Western landscape and wildlife.

Read our post about the National Museum of Wildlife Art.

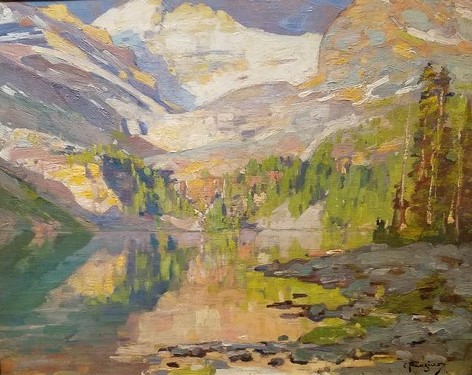

“You have to keep painting outdoors; if you paint outdoor scenes in your studio your color invariably gets too warm, too hot. Only if you paint outdoors do you see the cool silvery tones that are the true colors of nature.” – Carl Rungius

Carl Clemens Moritz Rungius (1869 – 1959) was born into a large family in Berlin that exposed him to art, nature, and taxidermy. From a young age Carl demonstrated a passion for both hunting and painting. As a teenager his ambition to make a career as an artist was reinforced when he saw an exhibition of work by Germany’s foremost animal and landscape painter, Richard Friese (1854 -1918).

Rungius’ father, a pastor, wanted Carl to become a minister, and strenuously opposed his son’s desire to be an artist. Eventually Papa Rungius relented, but only on the condition that Carl learn the trade of a house painter, so he’d have something to fall back on! Carl apprenticed as a wall and woodwork painter for three summers, but I’ve seen nothing to indicate that he ever painted another wall or trim-work after that!

He attended the Berlin Art Academy (1888–1890), and spent much of his free time sketching at the Berlin Zoo, studying the mannerisms and habits of the animals and striving for anatomical accuracy. In much the manner of Michelangelo and da Vinci, Carl wanted see how muscle, bone, tendon and tissue worked together to support and animate the living creature so, to further his knowledge, he frequented the local glue factory to study animal anatomy at its most basic. He admitted that it was an unpleasant undertaking, but he considered it critical to his artistic development.

When he was 25, Carl was invited on a moose-hunting trip in Maine, and from there he traveled to Wyoming, which proved to be a life-changing experience. The open skies, mountain scenery, and abundance of big game persuaded Rungius that he should make the United States his home. In 1896, he emigrated to the US. “My heart was in the West,” he said.

Rungius’ deep understanding of animal anatomy and his observation of wildlife in its natural habitat brought him to the attention of William Hornaday, the first director of the New York Zoological society. Hornaday introduced him to wealthy patrons who were crucial to Runguis’ success, and also introduced him to the lucrative world of illustration, which was in its golden age.

Rungius soon became sought-after as an illustrator for hunting and naturalist magazines and books, as well as for campaigns to protect endangered species.

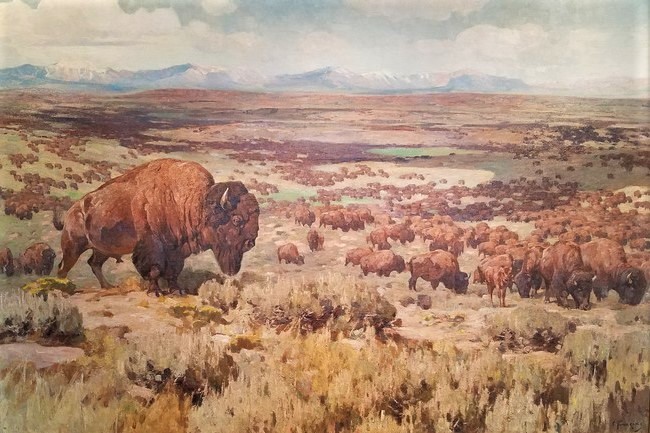

His arrival in the United States coincided with a new recognition of the plight of the continent’s game animal and bird populations. Several concerned sportsmen, most notably Theodore Roosevelt, had turned their attention to conservation, striving to end the waste of natural resources. Roosevelt established the United States Forest Service, signed into law the creation of five National Parks, and signed the 1906 Antiquities Act, under which he proclaimed 18 new United States National Monuments. He also established the first 51 Bird Reserves, four Game Preserves, and 150 National Forests.

Around 1909, Rungius gave up illustrating to pursue a career as a full-time easel painter. Nonetheless, his illustrations stayed in circulation for years, playing a significant part in spreading information about ethical hunting. In early 20th-century North America illustrations from books and periodicals were the main source of information about wildlife, as there weren’t many zoos and photography was in its infancy .

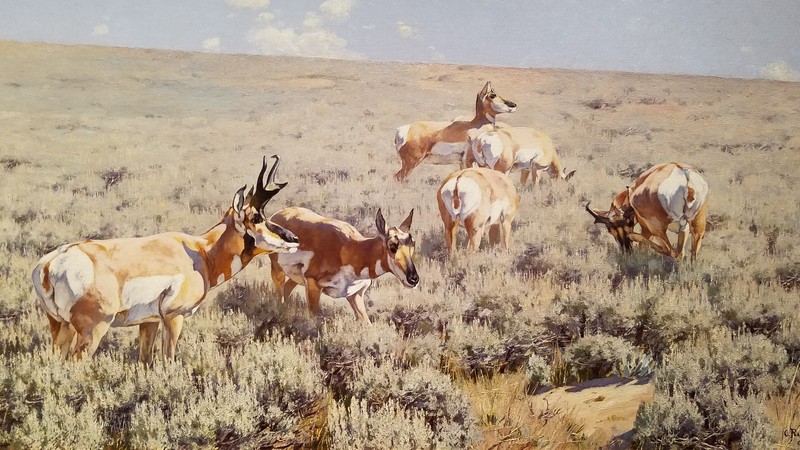

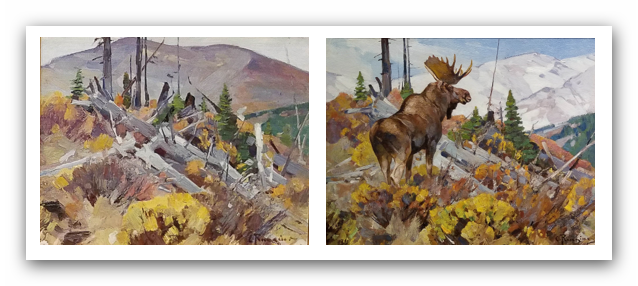

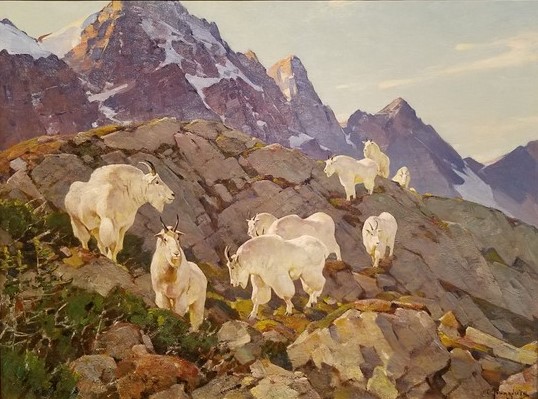

Rungius was an avid sportsman and he spent much more time in the wilderness than other artists. By direct observation in nature, he was able to gain exceptional insight into the animals and their environment. He painted landscapes and wildlife, often treating both in a single picture.

In a practice that was new to painting in North America, he showed animals in their natural habitat. He romanticized the landscape by representing nature as unspoiled by human impact.

As he matured, Rungius’ painting style evolved away from the academic approach he was taught in Germany. His palette lightened, and he incorporated elements of Impressionism into his painting.

Rungius took hunting and painting trips to New Brunswick province, the Yukon and the Canadian Rockies. He liked the latter so much he built a studio in Banff, Alberta, which he called “The Paintbox.” He referred to Alberta as “A province which has practically every species within its borders.” And he liked Banff because it was, “Easy to reach and a cosmopolitan, broad-minded town right in the wilderness, at the same time offering all the comforts of a big city.” He worked in his Banff studio from April to October every year until his death. Rungius died of a stroke while working at his easel in 1959.

the National Museum of Wildlife Art

In 1927, the Boy Scouts of America created Honorary Scouts to acknowledge “American citizens whose achievements in outdoor activity, exploration and worthwhile adventure are of such an exceptional character as to capture the imagination of boys…”. Rungius was one of eighteen who were awarded this distinction.

Preparatory sketches and finished works

Although Rungius’ paintings can be seen in many places, the largest holdings of his work are featured at the Dutch Rijksmuseum Twenthe, and Calgary’s Glenbow Museum, as well as the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson WY, which stewards the largest public collection of his work.

Hmmm… maybe it’s time to plan a trip!

National Museum of Wildlife Art

2820 Rungius Rd, Jackson WY

307-733-5771

Read our article about the Museum here.

By ArtGeek.art on May 15, 2018.

Exported from Medium on January 12, 2019.